A blog of the Science and Technology Innovation Program

Introduction

In February 2024, President Joe Biden visited East Palestine, Ohio, over a year after a Norfolk Southern train carrying hazardous chemicals derailed and caught fire. The visit was met with mixed reactions, with some criticizing the government’s response to the derailment. Residents have, for example, questioned the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s declaration that residents were not in danger from the town’s water, soil, or air, calling for answers and additional action after residents continue to report headaches, coughing, and other health concerns. Others have criticized Congress’ failure to pass rail safety legislation, pointing to the millions of dollars that Norfolk Southern and other industry players have spent in lobbying against increased regulation.

These criticisms demonstrate the importance of centering environmental justice, defined by the EPA as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people…with respect to the development, implementation and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies,” in environmental policy and action. Residents’ distrust of the government, Norfolk Southern, and other actors has hindered East Palestine’s recovery, leaving many community members in limbo over a year after the derailment.

A lack of transparency can create distrust: In East Palestine, delays by the EPA and Norfolk Southern in releasing testing results and data fueled frustration and criticism from community members and advocacy groups. Power and information asymmetries can also arise from a lack of transparency between researchers and local communities. These asymmetries often perpetuate injustice: “Parachute science,” for example, is a practice whereby outside researchers conduct research in low-income areas, then depart to publish their findings in a different space–without acknowledging local contributions or sharing the benefits of their research.

Open Science

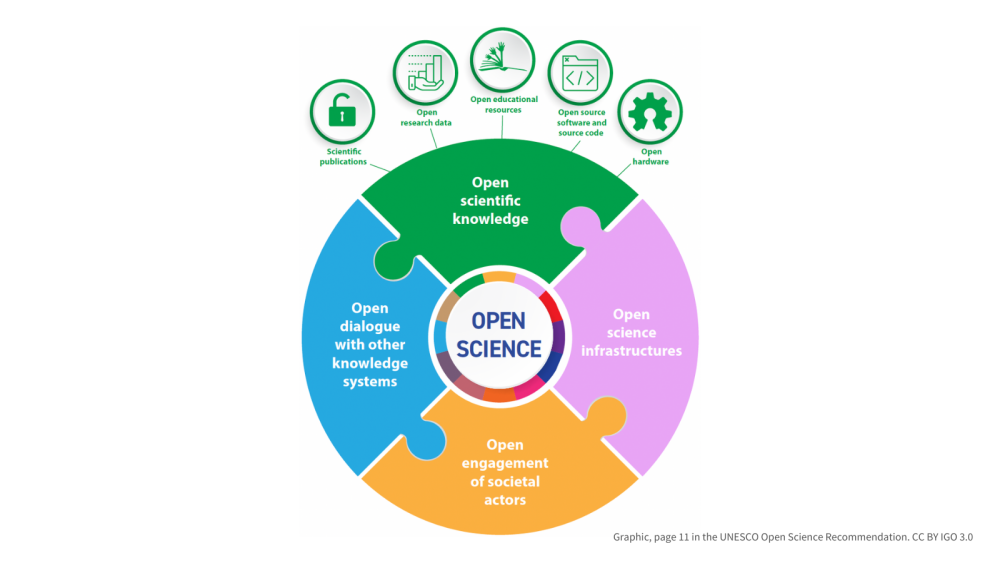

Open science is a commitment to making the products and processes of science more inclusive, accessible, and transparent; thus, it can offer an opportunity to rebuild trust and address asymmetries between the government, the scientific community, and the public. According to the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and the National Science and Technology Council, open science is “the principle and practice of making research products and processes available to all, while respecting diverse cultures, maintaining security and privacy, and fostering collaborations, reproducibility, and equity.”

Is open science a potential solution to advance trust and, in turn, environmental justice? Open science encourages researchers to make their findings and collected data publicly available, which can create direct and indirect benefits for local communities. The potential benefits for environmental justice are exemplified by a 2021 ProPublica investigation that used open data from the EPA to map how toxic air blooms around industrial plants spread into nearby neighborhoods, many of which were predominantly Black. In Verona, Missouri, the site of a manufacturing plant, the analysis led Mayor Joseph Heck to demand a state investigation into the city’s local cancer rate and to (successfully) fight for EPA air monitoring. 18 months after ProPublica’s report, the EPA proposed new air pollution rules for industrial facilities.

However, open science can also perpetuate distrust and exploitative practices. One ongoing challenge pertains to the relationship between open data and Indigenous Data Sovereignty, defined as “the rights of Indigenous Peoples to govern the collection, ownership, and application of their own data.” Indigenous Knowledge offers important benefits for conservation, sustainability, and other environmental action; however, environmental researchers often extract and exploit Indigenous Knowledge without appropriately engaging with Indigenous communities.

In its pursuit of making knowledge and data as accessible as possible, there is the potential that open science can infringe upon Indigenous Data Sovereignty and, in turn, engender mistrust between researchers and Indigenous partners. In the United States, for instance, Tribal members have raised concerns about whether the knowledge they share with federal or state agencies may be subject to disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

To address these concerns, the Global Indigenous Data Alliance developed the CARE Principles to center the people and purposes connected to data. These principles are:

- Collective Benefit: Indigenous Peoples should derive benefit from the data.

- Authority to Control: Indigenous Peoples and governing bodies have the right to control Indigenous data.

- Responsibility: Those working with Indigenous data have a responsibility to ensure the data are used to benefit Indigenous Peoples.

- Ethics: Data governance must center Indigenous Peoples’ rights and wellbeing.

Opening the Process of Science

Although conversations around open science often focus on sharing publications and data, open science also offers opportunities to involve stakeholders in multiple stages of research–as not just consumers, but also producers of knowledge.

For example, open hardware for environmental research offers a cost-effective and accessible way to break down silos between researchers and local communities and encourage communities to independently engage in research and monitoring. In Belize, AudioMoth–a low-cost, open source acoustic logger–has been tested as a potential method for detecting gunshots, to prevent poaching in protected nature preserves. Similarly, in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, AudioMoth was deployed to help local rangers and managers regulate the hunting of jaguars and pumas. The team’s goal is to ensure that “local communities can afford to monitor their own natural resources.”

Making not just the products, but also the process of science more inclusive is crucial to the advancement of environmental justice. As Professor James T. Gathii expresses in the Wilson Center’s International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples collection, “environmental justice recognizes those disproportionately impacted by climate change not merely as victims or objects of study, but also as producers of knowledge whose agency in exposing and countering environmental injustices is crucial to understanding the threat that climate change poses.”

Conclusion: Looking Forward

During his visit to East Palestine, Ohio, President Biden stated, “We've tested the air, the water, the soil quality.” EPA Administrator Michael Regan told reporters that “We believe, and know, based on the science and the data, that the air is safe.” Yet the community remains divided over, and distrustful of, these and other assurances. Whether warranted or not, the distrust that persists in East Palestine demonstrates the need for a different approach to environmental research, policy, and action.

The President also announced six new National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants to top universities for studying the short- and long-term effects of the derailment. Open science practices, principles, and values could help expand the community’s trust in, and thus the impact of, the research that these grants produce.

For policymakers and researchers alike, open science often encourages us to move away from rigid top-down hierarchies and information silos, towards greater collaboration and transparency. This paradigm shift has the potential to transform our efforts to build not just a more sustainable, but also a more equitable, future.

Authors

Science and Technology Innovation Program

The Science and Technology Innovation Program (STIP) serves as the bridge between technologists, policymakers, industry, and global stakeholders. Read more