A blog of the Polar Institute

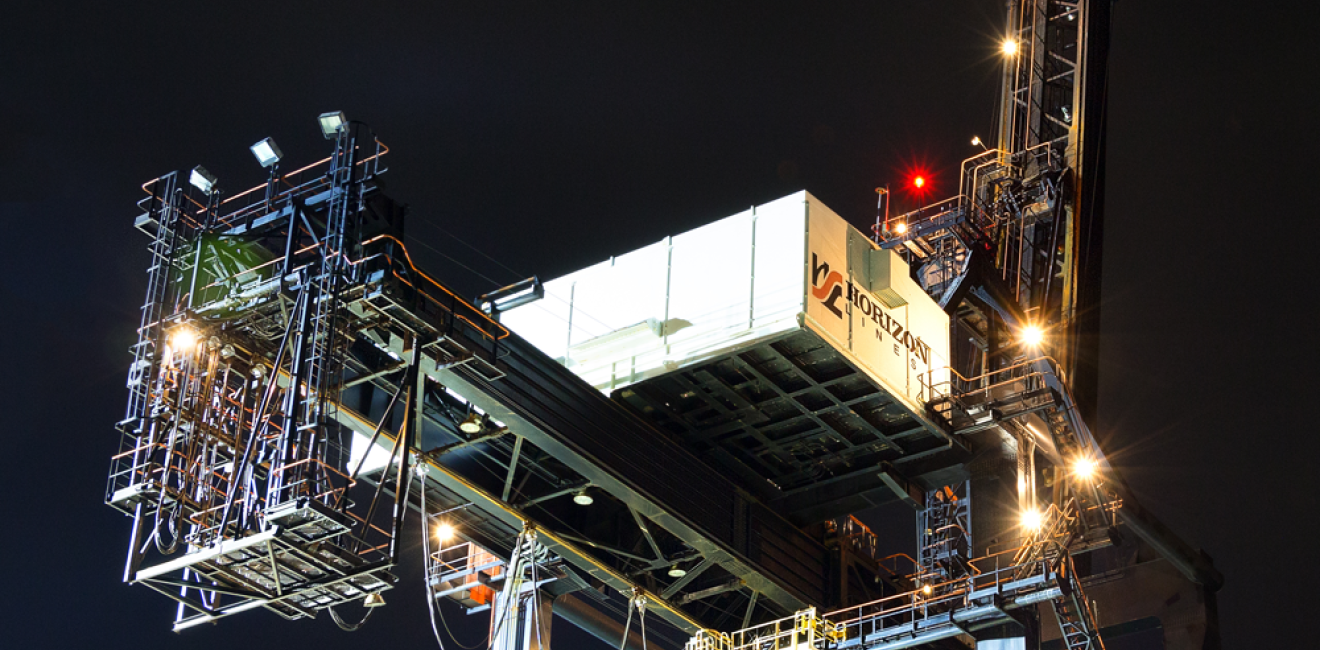

Unalaska, an island community of 4,500 sandwiched between the North Pacific and the Bering Sea, will soon be forever changed. By 2022, the nation’s largest fishing port will connect to mainland Alaska and the broader world via an 800-mile undersea cable that will replace the community’s existing satellite internet with high-speed broadband. For the first time, residents will have fast and affordable access to the internet.[1]

Unalaska’s transformation is part of a broader effort in the Arctic to address infrastructure gaps and build healthy, safe, and resilient communities. Across the region, the physical and digital infrastructure that enable daily life in an integrated, globalized world—roads, ports, power grids, internet cables—are all too often inadequate, outdated, or nonexistent. As a result, the cost of goods is higher, it takes longer to travel anywhere, and access to basic services (including emergency services) is unreliable —factors that weigh heavily on physical and mental health and prevent communities from reaching their full potential.

For decades, experts have recognized the Arctic’s infrastructure gap and the impact it has on regional security, economic growth, and the public’s general welfare. As Polar Institute Director Mike Sfraga wrote in a recent editorial, “The basic Arctic infrastructure deficit presents serious economic, social, political, national, and environmental security implications.” Recognizing the problem, however, is only the first step toward a solution. Understanding it is the next.

That is why the Polar Institute recently launched the Arctic Infrastructure Inventory (AII), a digital catalog of current and proposed infrastructure projects in the Arctic. With over 8,000 entries and coverage across all eight Arctic states, AII is the most comprehensive effort to date to quantify the size and scale of the Arctic’s infrastructure gap. Thoughtfully constructed and thoroughly researched, it aims to be a public resource advancing informed policy discussions, infrastructure development, direct investment, and scientific research.

To that end, the current version of AII offers a preliminary estimate of infrastructure requirements in the Arctic. It catalogs 64 partially-funded and permitted infrastructure projects valued at $69.4 billion, with an additional 98 proposed projects valued at $265.5 billion. Projects range from airports and roads to wind turbines and fiber optic cables, although most are tied to resource extraction. In the United States and Canada alone, 65 of 100 in-progress or proposed projects are linked to the development of new oil and gas fields or mines.

While AII’s coverage of some sectors is robust, gaps remain. The largest and most obvious is that of projects with an estimated cost below $10 million. Because the original dataset was built to identify opportunities for private investment, it only included projects with an estimated cost of $10 million or more. AII faces no such dollar-figure limit, but it still undercounts small-budget projects, particularly those financed wholly by governments or other public entities (e.g. community centers, health clinics, water and sewer systems). Given the likely number of projects in each community, and the number of communities overall, the aggregate value of missing projects is likely in the range of several billion dollars.

Additionally, the current version of AII does not include deferred maintenance costs. However, deferred maintenance is an under-reported cost and an undercover problem across the Arctic, where getting spare and replacement parts as well as qualified mechanics has always been difficult. As demonstrated by the massive diesel spill in Norilsk earlier this year, where a storage tank collapsed due to neglect and thawing permafrost, maintenance that has been deferred for too long can pose a real threat to both Arctic communities and the environment.

Closing these gaps will be AII’s primary focus in the coming months, though it will not be easy. Existing data on Arctic infrastructure is limited, with open-source coverage focusing on a handful of large, well-publicized projects like oil and gas fields, mines, pipelines, railroads, and ports. This has the effect of crowding out smaller projects, particularly those limited to a single community, restricting efforts to gain a fuller, more nuanced, and unbiased picture of overall regional development.

It is thus important to view the current version of AII not as a definitive database, but as the first step in the long process of understanding and meeting the Arctic’s infrastructure requirements. In time, AII will close the gaps and provide increasingly comprehensive coverage of the region. For now, we hope it is a useful if basic tool for those interested in sustainable development and the future of the Arctic.

[1] https://www.anchoragepress.com/news/gci-pushes-ahead-with-58-million-fiber-optic-link-to-unalaska-building-out-western-alaska/article_321862a2-22c4-11eb-8b36-8fb0d94bf340.html; https://www.alaskajournal.com/2020-10-21/alaska-receives-465m-grants-remote-broadband

Authors

Director of Business Development, Alaska Ocean Cluster

Polar Institute

Since its inception in 2017, the Polar Institute has become a premier forum for discussion and policy analysis of Arctic and Antarctic issues, and is known in Washington, DC and elsewhere as the Arctic Public Square. The Institute holistically studies the central policy issues facing these regions—with an emphasis on Arctic governance, climate change, economic development, scientific research, security, and Indigenous communities—and communicates trusted analysis to policymakers and other stakeholders. Read more

Explore More in Polar Points

Browse Polar Points

Ever Forward: The Unique Relationship Between the Arctic and Space

Sea Ice in 2024 – The New Abnormal

Norway’s Supposed Arctic Seafloor Treasures: What Does the Data Show?