Presidential Accountability in Russia and the United States

The "accountability of public officials–or the perceived lack of it–is a serious problem for democratic societies worldwide and even more so for quasi-democratic societies such as Russia," began Martha Merritt, Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame, at a 17 March 2003 Kennan Institute lecture. She explained that democratic political accountability is "distinguished by a complex web of monitors and checks that functions to limit the ability of leaders to craft public policy leading to undue harm," as opposed to the kind of rapid redress that some desire. According to Merritt, "accountability by its very nature is a peculiar phenomenon in political life, and must be understood as an ex post facto phenomenon, not something that can happen simultaneously with action or even before it." Merritt posited that an automatic tension exists between accountability and political power, as those in office seek to limit political accountability while those out of power seek to enhance it, and that this tension is particularly interesting in the cases of Russia and the United States.

Merritt discussed how war functions as a constraint on political accountability in both Russia and the United States. She explained that in Russia, "war has been a fundamental part of the exercise of federal state-building," and is "meant to legitimate and enhance presidential power." The handling of both the first and second Chechen crises helps illustrate how war has limited the political accountability of President Putin and his predecessor President Yeltsin, Merritt noted. She argued however, that despite its relatively brief history and limited role, political accountability does still exist in Russia. She explained that the Russian political environment is far more complex than it once was and certain elements do exist which could provide "proto-accountability." Merritt contended that in the Russian case, accountability is obviously an ex post facto phenomenon, and democratic tools such as elections have not proven to effectively impose accountability on Russian leaders.

According to Merritt, President Putin has created a "two-track system" of political accountability in Russia. She explained that Putin and other government officials have been relatively straightforward in addressing foreign policy controversies yet provide little information or justification on domestic matters. Using the latest Chechen crisis as an example, Merritt explained how the regime has effectively stifled domestic and foreign media coverage of the human rights abuses in Chechnya itself. But the aftermath of the gassing of hostage-takers and captives in the Moscow theater showed a clear divide between domestic and foreign press that could not be attributed to pressure from the regime alone. Merritt said that the Chechen war has taken on a peculiar power in the Putin presidency, allowing the President "to appear as the champion of the Russian people, while keeping the military busy in a war that is not going well."

Merritt noted that in the case of the United States, war is treated differently because communication between people and president requires that "the United States takes a lot longer to mobilize its war machine." She stated that "accountability as the voice of the opposition calling for constraints on the exercise of power is a very complex matter when a country is at war because there is this sort of Teflon shield that goes up as we rally as one nation." Merritt suggested that one major difference between the Russian and U.S. cases is that while the Chechen crisis serves to expand presidential power in Russia, the U.S.-led war in Iraq comes as part of a "package meant to reduce federal power." According to Merritt, the most dramatic difference between the two systems is that the U.S. president has proven able to launch a war effort that is extremely unpopular worldwide and elicits mixed responses at home because he is "borrowing on centuries of credibility for American presidential authority."

Differences in the potential for presidential accountability in Russia and the United States also have structural roots in the powers of the president, in addition to the obviously fewer constitutional checks and balances in Russia. Merritt noted that in the Russian Constitution, the president is not defined as part of the executive branch, though he oversees it. Therefore, the Russian president is structurally accountable to fewer forces than the U.S. president, who heads the executive branch and belongs to a political party.

Merritt concluded by reminding the audience that however unsatisfied Americans might feel about accountability in American politics, it is important to recognize that "there is a web of monitors gathering information that has the potential to hold U.S. public officials to account," though not in "real time." She stressed that in Russia monitoring bodies "find it increasingly difficult to gather information that has the potential to hold the Russian president to account." Merritt reiterated that because accountability is an ex post facto exercise, "it will always leave people hungry for democracy feeling dissatisfied."

Author

Ph.D.candidate, Department of Politics, University of Virginia

Kennan Institute

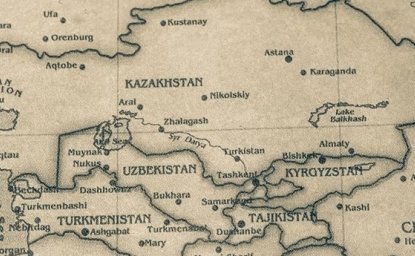

The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region though research and exchange. Read more