Kennan Cable No. 68: Central Asia’s Multi-vector Defense Diplomacy

The post-Cold War order is eroding in strategic theatres across the globe. Economic and political power is shifting east, and the rules of the game are being re-written. Amid these tectonic shifts, Central Asian leaders are better placed to pursue multi-vector foreign policies, balancing neighboring powers and creating a wider array of strategic partnerships than the region has seen since independence. Across the board, the Central Asian republics are embedding their defense sectors within diffuse new networks of arms suppliers, instructors, and partners across Europe, Asia, and North America.[1]

China’s growing role in Central Asia’s security sector is clear. Beijing has provided 13 percent of the region’s arms over the past five years, a significant increase from the 1.5 percent of Central Asian arms imports that it provided between 2010 and 2014.[2] Meanwhile, the United States is largely exiting the region. While Washington’s security establishment fears that Beijing will fill vacuums left behind by U.S. retrenchment, Central Asia suggests a more complex picture. China, the U.S., Russia, Europe, and an increasingly assertive India, driven by concerns over spillovers from Afghanistan, have each projected a significant degree of military power in the region.

Russia remains the main external security partner for Central Asia, with military facilities in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, and the lion’s share of the regional arms market, at 52 percent. But in recent years Central Asian states like Uzbekistan have shown an unprecedented degree of leadership in initiating new channels for nascent regionalism, allowing the countries to take advantage of an emerging multipolar system and signal to external powers that they can address regional issues without outside help.

Defense Diplomacy in Central Asia: An Overview

In recent decades, defense diplomacy has emerged as one of the key tools of statecraft as governments seek to maximize their influence at minimal cost. Defense diplomacy refers to the state’s pursuit of foreign policy objectives through the peaceful use of its military and security apparatus. The concept is now used as a catch-all term encompassing the full gamut of activities from officer exchanges, training missions, arms transfers, and strategic aid, to joint military exercises designed to enhance interoperability between national units.

This report focuses on the latter aspect, analyzing trends from a comprehensive new dataset we created of 256 joint exercises involving Central Asian militaries since 1991. The dataset collects available information on the countries involved, the number of troops that participated, the weapons systems deployed, and the nature and strategic emphasis of the operations.

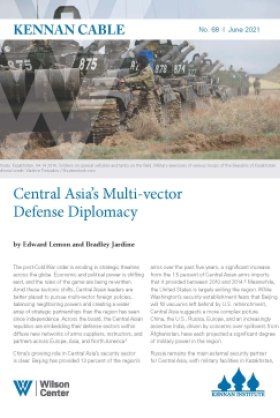

Figure 1: Joint Military Exercises Since 1991 by Organizer[3]

Russia and Russian-led organizations, such as the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), account for the bulk of exercises, with some 110 conducted under Moscow’s auspices since 1991 (see Figure 1). The U.S. and NATO collectively account for 85, but with numbers dropping from a peak of seven in 2003 to an average of two since 2018. While China’s share has grown from 11 percent in the first half of the 2010s to 14 percent in the second half—both bilaterally and under the umbrella of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO)—it lags behind Russia and the U.S. in absolute terms, with just 32 exercises. India has organized 12 drills to date, 10 of which took place in the past five years, signaling its growing interest in the region as its military capabilities increase.[4]

Overall, the trends point to the declining role of the U.S, which has cut its exercises by half over the past 20 years. China’s share in exercises has remained relatively steady, while Russia’s has increased, from 39 percent in the first decade of the 21st century to 49 percent in the second. A similar picture emerges with regards to scale, with Russian exercises being the largest, followed by those of China and the U.S. While India’s rising number of exercises looks impressive on the surface, the reality is that the exercises are relatively small, with an average of 90 participants.

Figure 2: Average Size of Exercises by Country

Country

Average Size of Exercise (Number of Troops)

Russia (including CIS & CSTO)

4,467

China (including SCO)

1,844

United States

1,295

India

90

The active promotion of political, economic, and security ties between countries to address collective interests reflects a growing regionalism. Since the death of Uzbek President Islam Karimov in 2016, there has been a growth in bilateral exercises involving just Central Asian militaries, with seven exercises, five of which have occurred since 2018. A catalyst for this development was the ascendance of President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, who has made strengthening regionalism the centerpiece of his foreign policy—a sharp U-turn from his predecessor’s isolationism. Regime transition in Uzbekistan has also opened up political space for outside cooperation. In 2017, Russia held its first exercise with Uzbekistan in 12 years, signaling a revival of security ties. India conducted its first exercise with the country in 2019, and in that same year China began a series of new exercises with the Uzbek National Guard.

Multi-Vectorism and Declining Engagement with the United States

Defense diplomacy first gained traction as part of national strategic doctrines in the 1990s, following the end of the Cold War. Western powers feared at the time that the large Soviet-style armies of former Warsaw Pact countries would act as significant stumbling blocks in the process of democratic transition. NATO was the first organization to hold a joint exercise involving the Central Asian militaries in 1995. Later NATO exercises emphasized interoperability with NATO and Partnership for Peace members, a program in which all five Central Asian states still participate in today.

Exercises involving NATO peaked in 2002 in the aftermath of the invasion of Afghanistan, as the U.S. sought to prepare Central Asia’s militaries for potential spillovers from their southern neighbor. At that time, three member countries had NATO-aligned bases in the region, with the U.S. overseeing a base in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, Germany in Uzbekistan, and France operating a small logistics center in Tajikistan. By 2015, all these bases had been closed and the Northern Distribution Network, a sprawling web of supply lines to Afghanistan via Russia and Central Asia, had been shuttered. In 2017, NATO closed its liaison office for Central Asia in Tashkent, citing budgetary constraints, and further signaling the organization’s lack of interest in the region.[5]

This drawdown reflected both NATO and individual member states’ declining interest in the region, with the planned withdrawal of troops in Afghanistan, and Russia’s annexation of Crimea and support for separatism in Ukraine drawing away strategic attention and causing Russia to pressure the Central Asian republics into pushing the U.S. out.

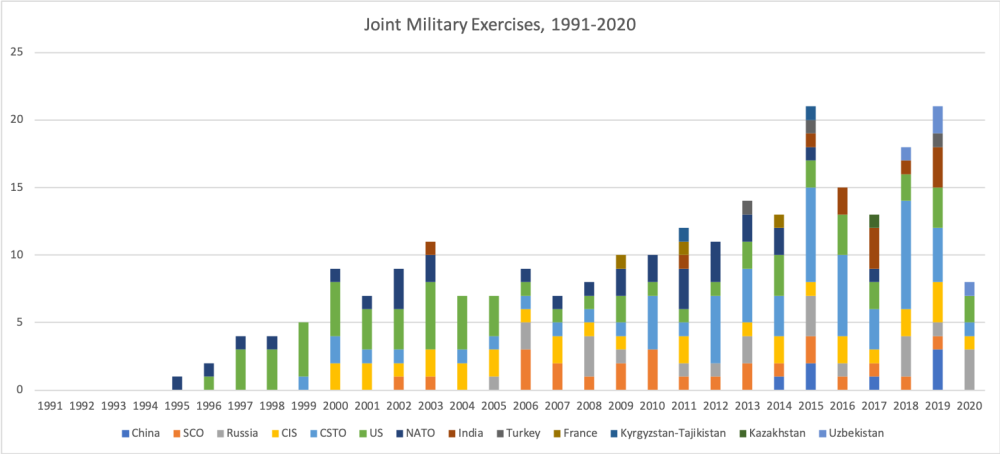

Figure 3: U.S.-led Joint Exercises in Central Asia

The U.S. has typically relied on bilateral engagement with the region. Since organizing its first exercise, Balance Ultra, held in 1996 in the Ferghana Valley in Uzbekistan, it has organized at least 88 additional joint exercises. The vast majority (71 percent) involved army units, with others involving peacekeeping units (19 percent), emergency services (9 percent), and special operations forces (7 percent). The largest exercise, Khaan Quest-2016, involved 2,000 troops, but also included contingents from Russia, China, and Mongolia. But as the U.S. has slowly withdrawn from Afghanistan and lost any hope of the Central Asian republics adopting systems of governance in keeping with its values, the general trend in terms of U.S. involvement in joint exercises is downward, with the peak of five exercises in 2003 declining to one or two per year since 2006. This has moved in step with a precipitous decline in U.S. military aid and assistance to the region, which has fallen from a high of $450 million a decade ago to just $11 million in 2020.[6]

China’s Internal Security Forces March West

Since the 2014 launch of the People’s War on Terror in China’s westernmost province of Xinjiang, Beijing has been taking a more active role in defense in Central Asia, seeing it as a bulwark preventing instability in Afghanistan from pouring across its western borders. This has led China to focus primarily on cooperation between its internal security services and those of neighboring states. But China is also boosting its geopolitical ambitions.

In a landmark January 2015 speech, Chinese President Xi Jinping cited several specific goals for military diplomats at the All-Military Diplomatic Work Conference, including supporting the overall foreign policy objectives of the country, protecting national security, and building strategic capacity. Since then, Chinese strategic initiatives have surged worldwide. According to data gathered by the CSIS China Power blog, from 2003 to 2012, China averaged 151 military activities per year, rising to 179 between 2013 and 2018—a 20 percent increase. But the raw numbers obscure a crucial qualitative shift.[7] Over the first nine years described above, 90 percent of these interactions consisted of senior-level visits. However, since his ascent to power, Xi Jinping has emphasized the importance of combat readiness. From 2016 to 2018, senior-level meetings accounted for just 56 percent of all military-diplomatic activity, with drills and joint-training exercises growing in importance.

This shift has been particularly notable in Central Asia. In 2002, China took part in its first known bilateral exercise, with Kyrgyzstan. The drill, organized under the auspices of the SCO, involved only a small cohort of some 100 soldiers armed with light weapons, anti-tank missiles, helicopters, and armored personnel vehicles. It was not until August 2003, in eastern Kazakhstan and Xinjiang, that the first multilateral Chinese-led military exercises took place. All member states, except Uzbekistan, participated. Since then, the picture has begun to shift drastically.

Figure 4: Military Exercises by Military or Security Institutions Involved

China

United States

Russia

Security Services

59%

Army

71%

Army

65%

Special Operations Forces

47%

Peacekeeping Units

19%

Air Force

57%

Army

38%

Emergency Services

9%

Special Operations Forces

25%

Police

28%

Special Operations Forces

7%

Security Services

19%

Air Force

25%

National Guard

4%

Police

13%

Almost 59 percent of China’s exercises involve security services, with special operations forces and police units following close behind, showing a very different strategic orientation to that of other major actors in the region (see Figure 4). These reflect China’s domestically oriented security interests. In 2014, President Xi Jinping made a number of secret speeches in the bordering Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), since leaked to the New York Times, in which he expressed concern that “Uyghur fighters” could return from Syria and use Tajik territory as a transit zone.[8]

To enhance stability on its border, China launched “Cooperation-2019,” a series of drills allowing it to enhance the interoperability of local paramilitary units with its own People’s Armed Police (PAP). Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan all took part, marking the first time their national guard units had trained with Chinese counterparts on counterterrorism. A few years before, the Chinese Ministry of Public Security (MPS) conducted its first training exercises overseas in 2015, when MPS forces trained with their Tajik counterparts near Dushanbe.

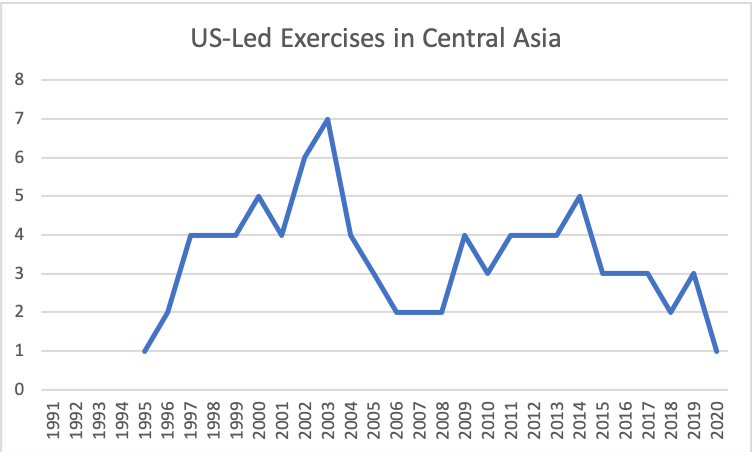

Figure 5: China-led Exercises by Weapons Deployed

The security-focused nature of the drills may serve an additional purpose of placating Russia, which sees itself as the prime security-guarantor of the region. China has shown deference to Russia on such matters in the past and tends to inform Moscow well in advance of its policies. In 2017, the Development Research Center, a powerful think tank under China’s cabinet, invited a number of Russian researchers to a private seminar to ascertain Moscow’s red lines on what is and is not acceptable Chinese regional policy.[9]

Russian Firepower on the Rise

Moscow continues to view Central Asia as a part of its Near Abroad, or sphere of influence, an area of potential political instability and a pathway that could allow violent extremism to enter Russia. This threat perception has guided policy in the region since the collapse of the Soviet Union and has justified the maintenance of its outsized security role in the region. Both Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan continue to host Russian military bases, and both nations remain highly dependent on Moscow to build up their security capacities.

Figure 6: Russia-led Joint Exercises

Russia, either on its own or through the CIS and CSTO, has organized an increasing number of joint exercises in Central Asia, peaking with 13 in 2018, and then dropping off suddenly in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Russia still conducts most of its exercises through the CSTO, with 45 of the 115 exercises that have taken place with Russian involvement since 2004 occurring within this framework. The key CSTO exercise series in recent years is the Combat Brotherhood series. In 2018, it took place as an operational-strategic level exercise series covering various stages of a simulated conflict in Central Asia. The CIS, which has organized 34 exercises in the region, has largely focused on joint air defense under the framework of the Joint CIS Air Defense System, launched in 1995. Russia has also organized its own bilateral exercises or invited Central Asian militaries to participate in its annual Tsentr exercises. Of the 22 Russian-organized exercises, 10 have occurred in the past five years.

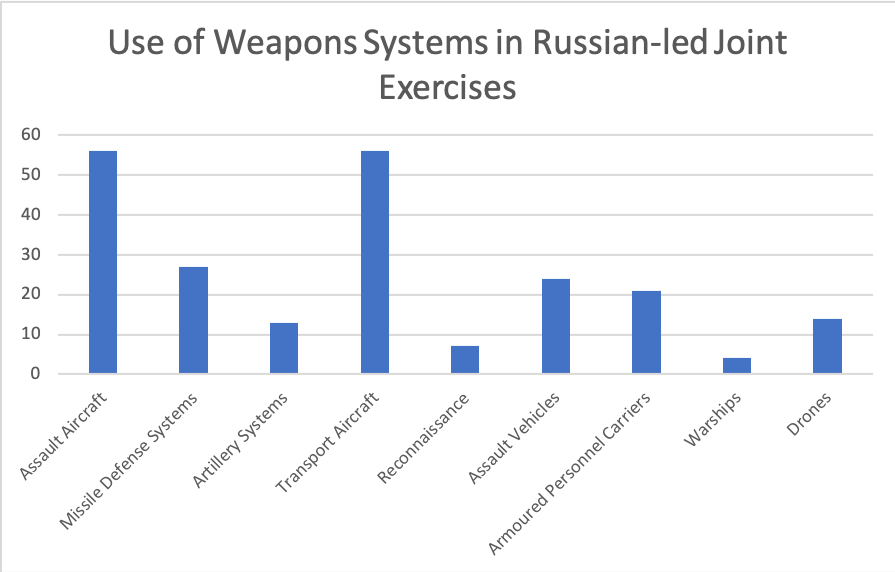

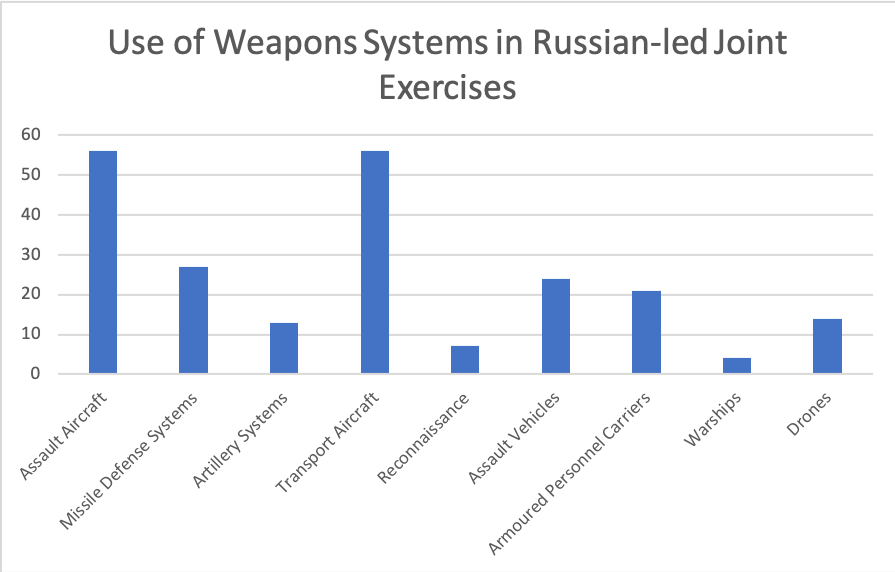

More than any other external power, Russia tends to deploy heavy weaponry during its exercises, with over half involving assault aircraft, a quarter using assault vehicles, and 28 percent involving missile defense systems. Such power projection is facilitated by Russia’s 12 military facilities in the region, including the Soviet-era 201st Motorized Rifle Division’s base in Tajikistan. Re-established in 1992 by Boris Yeltsin, the base is now Russia’s largest abroad, housing 7,000 troops, 100 main battle tanks, 300 infantry fighting vehicles, and a number of helicopters and ground-attack aircraft. The Kant Airbase, just outside of Kyrgyzstan’s capital city Bishkek, was opened in 2003 under the auspices of the CSTO.

Russia’s exercises often involve tens of thousands of troops and focus on the army (65 percent of exercises) and air force (57 percent) more than the security services (19 percent) and police (13 percent), institutions that China has prioritized cooperation with (see Figure 4).

Figure 7: Russia-led Exercises by Weapons Deployed

This division of tasks helps dampen competition between Russia and China, allowing them to pursue complimentary agendas of limiting U.S. influence and securing the rule of autocratic client states. Competition is further softened through a number of joint exercises binding the two powers, such as the widely publicized Vostok-2018 and Center-2019 drills.

India Enters the Fray

India was slow to take an interest in Central Asia following independence. By 2000, trade stood at just $94 million and military cooperation was negligible. But the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and the subsequent stationing of U.S. troops in the region, coupled with a desire to contain Pakistan, drove it to become more active in Central Asian security matters. In 2001, India set up a small field hospital at Farkhor in Tajikistan and the next year began renovation work of the Ayni air base in Tajikistan in 2002, its first attempt to set up a military base in the region to monitor conflict-torn Afghanistan and the activities of Pakistan.[10] In the period after 9/11, India stepped up defense cooperation with the region by signing agreements on counterterrorism and military cooperation with Tajikistan in 2003 and Uzbekistan in 2005. Ties were symbolically upgraded to strategic partnerships in 2009 in Kazakhstan, 2011 in Uzbekistan, 2012 in Tajikistan, and 2019 in Kyrgyzstan.

With India’s accession to the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation in 2017, ties have also strengthened. This renewed focus on Central Asia can be attributed to the changing geopolitics of the region, particularly the formation of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and growing external security threats. As it has sought to strengthen ties with Central Asia, India has organized a growing number of exercises, with 10 of the 12 exercises it has organized coming in the past five years. India held its first military exercise in Tajikistan in 2003, at the time it was trying to establish its airbase in Ayni. Its second exercise, this time with Kyrgyzstan, followed in 2011, involving just 20 troops.[11]But since 2015, India has ramped up its activities in the region, organizing five further exercises with Kyrgyzstan, holding its first exercise with Kazakhstan in 2016, and then holding the KAZIND exercises annually since 2018, and a first exercise with Uzbekistan in 2019. Early exercises involved special operations forces and focused on joint counter insurgency and counterterrorist operations in urban and rural environments, as well as mountainous terrain. Since 2018, cooperation has switched to focus on the army. But these exercises are largely symbolic, with fewer than 200 personnel involved in each, and are driven by India’s desire to brandish its credentials as a world power, as well as signal its interest in Central Asia to rivals China and Pakistan.

Rising Regional Cooperation

For many years following independence, Central Asia was one of the least integrated parts of the world in terms of regional trade, investment, and multilateral cooperation. Regionalism was often enforced by external powers pursuing their own agendas. But since the turnover in power in Uzbekistan in 2016, this has started to change: Uzbekistan has reopened borders, increased regional trade ties exponentially, and begun development on new joint projects.

Defense diplomacy between the Central Asian states has also grown in recent years, with eight joint exercises since 2011. The first joint exercises between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan was a small, largely symbolic affair involving around 30 troops. This was followed by a second exercise in 2015. A first exercise, Sapper’s Friendship, took place between Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan in 2017.[12]

In a move that would have been unthinkable a decade earlier, when tensions between Uzbekistan and Tajikistan were at their peak, the two countries held their first bilateral exercise, Jaihun-2018, in the south of Tajikistan.[13] Tajikistan and Uzbekistan signed an agreement on military-technical cooperation in March 2019, envisaging bilateral exercises and joint production of military equipment.[14] Under the new agreement, the two countries have held three further exercises, all involving special operations forces. The latest exercise, in March 2020, was the largest to date, with 400 troops, drones, armored vehicles and personnel carriers deployed.[15] A month later the two countries signed an agreement on intelligence sharing.[16]

Uzbekistan’s emergence as a lynchpin in Central Asian regionalism challenges the position of the region’s richest state, Kazakhstan. But rising regionalism also allows the governments to address regional issues, such as border delimitation, collective security, and trade without external mediation from Russia, the U.S., and China, potentially decreasing their influence in these areas in the future.

Conclusion: Central Asia Asserts Itself

Burgeoning global multipolarity offers the Central Asian states more options as they pursue their multi-vector foreign policies and attempt to avoid becoming overly dependent on any one external partner. Even as the U.S. is slowly reducing its role in Central Asian security, other options for defense cooperation exist. China’s role, at least in terms of exercises, has been relatively steady, but its internal security forces are establishing important footholds across the region, with potential political ramifications in the medium-term. India’s efforts remain largely symbolic for the time being, with plenty of agreements, but little substantive cooperation beyond some small-scale exercises. Russia, meanwhile, remains the dominant external security partner for the region, organizing its largest exercises. It has actually increased its share in recent years, despite the rising role of China and India.

Since Mirziyoyev became president of Uzbekistan in 2016, he has reinvigorated regionalism and the Central Asian states are stepping up intra-regional defense diplomacy, signaling to each other and to external powers that they have the potential to cooperate and develop military capacity without external assistance. These developments point to a dynamic region that is successfully cooperating with a range of partners and capitalizing on an emerging multipolar system.

[1] Bradley Jardine and Edward Lemon, “In Russia’s Shadow: China’s Rising Security Presence in Central Asia,” Kennan Cable 52 (May 2020), https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/kennan-cable-no-52-russias-shadow-chinas-rising-security-presence-central-asia

[2] Bradley Jardine and Edward Lemon, Avoiding Dependence? Central Asian Security in a Multipolar World (Washington, DC: The Oxus Society, September 28, 2020), https://oxussociety.org/avoiding-dependence-central-asian-security-in-a-multipolar-world/

[3] Please note the 2020 exercise figure is lower due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

[4]See Stephen P. Cohen and Sunil Dasgupta, Arming Without Aiming: India's Military Modernization (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2010), https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/armingwithoutaimingrevised_chapter.pdf

[5] Joshua Kucera, “NATO Closes Shop in Central Asia,” Eurasianet, November 17, 2016, https://eurasianet.org/nato-closes-shop-central-asia

[6] Figures are from the Security Assistance Monitor (website), https://securityassistance.org/

[7] China Power, “How is China Bolstering its Military Diplomatic Relations?” October 27, 2017, updated August 26, 2020, https://chinapower.csis.org/china-military-diplomacy/

[8] Austin Ramzy and Chris Buckley, “‘Absolutely No Mercy’: Leaked Files Show How China Organized Mass Detentions of Muslims,” New York Times, November 16, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/11/16/world/asia/china-xinjiang-documents.html

[9] Gerry Shih, “In Central Asia’s Forbidding Highlands, a Quiet Newcomer: Chinese Troops,” Washington Post, February 18, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/in-central-asias-forbidding-highlands-a-quiet-newcomer-chinese-troops/2019/02/18/78d4a8d0-1e62-11e9-a759-2b8541bbbe20_story.html

[10]Catherine Putz, “Will There be an Indian Air Base in Tajikistan?” The Diplomat, July 15, 2015, https://thediplomat.com/2015/07/will-there-be-an-indian-air-base-in-tajikistan/

[11] “India, Tajikistan to hold Military Exercises,” Silliconindia, February 13, 2003, https://www.siliconindia.com/shownews/india-tajikistan-to-hold-military-exercises-nid-18553-cid-Top.html

[12] “В Казахстане завершаются совместные учения инженерных подразделений ‘Саперлер достығы-2017’” [Joint Exercises of Engineering Divisions "Minesweeper Dostygy-2017" Coming to an End in Kazakhstan], Inform, August 25, 2017, https://informburo.kz/special/v-kazahstane-zavershayutsya-sovmestnye-ucheniya-inzhenernyh-podrazdeleniy-saperler-dostyy-2017.html

[13] "Узбекистан перебросил свой войсковой контингент на север Таджикистана" [Uzbekistan Has Transferred Its Military Contingent to the North of Tajikistan], Asia Plus, November 17, 2018, https://asiaplustj.info/ru/news/tajikistan/security/20180917/258947

[14] “Tajikistan, Uzbekistan Intend to Establish Joint Production of Military Equipment,” AzerNews, March 6, 2019, https://www.azernews.az/region/146868.html

[15] Umida Hashimova, "Uzbekistan and Tajikistan Engage in Joint Military Exercises," The Diplomat, March 23, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/03/uzbekistan-and-tajikistan-engage-in-joint-military-exercises/

[16] “Uzbekistan, Tajikistan Boost Security Cooperation,” UniPath, January 5, 2021, https://unipath-magazine.com/uzbekistan-tajikistan-boost-security-cooperation/

Authors

President, Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs; Research Assistant Professor, The Bush School of Government and Public Service, Texas A&M University (Washington, D.C. Teaching Site)

Director of Research, Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs

Kennan Institute

The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region though research and exchange. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Israel Expands Buffer Zone and Launches Hundreds of Airstrikes on Syria

Уехал на СВО

The Structural Redesign of Security in Mexico