Kennan Cable No. 44: Ukrainian Local Governance Prior to Euromaidan: The Pre-History of Ukraine’s Decentralization Reform

Introduction

Democratic states often decentralize power because the dispersion of prerogatives and responsibilities improves the involvement of ordinary people in government. Political elites in semi- or non-democratic states, in contrast, tend to prefer power concentration, as they benefit from centralized decision-making and implementation; policymakers in regionally diverse states may promote centralized power in order to prevent secession.

Yet in spite of authoritarian arguments for maintaining or increasing centralization, a high concentration of power in a country’s capital often hinders rather than fosters sustainable state building. Developmental, patriotic, and social narratives may be used to justify limitations on regional or municipal autonomy, but such restrictions on local self-government can eventually lead to lower efficiency in delivering public services, encourage separatism, and inhibit economic growth.

The case of post-Soviet, and especially post-Euromaidan, Ukraine highlights the importance of properly framing center-periphery relations in democratic transformations. Since its independence in 1991, Ukraine has experienced a constant struggle between bottom-up demands for decentralization and top-down policies of centralization accompanying political battles between its presidents, parliaments, and governments. Instead of increasing state efficacy, institutional centralization in Ukraine has undermined the government’s capacity to deliver public services.[1]

Ukraine’s centralized state was also unable to meet challenges to its territorial integrity. Only after the Euromaidan Revolution was there a serious reset of center-periphery relations. Both voters and policymakers in Ukraine quickly prioritized decentralization for the sake of increasing democratic processes; this was also seen as improving the resilience of the state vis-à-vis complex external and internal pressures.

The local governance reform that started immediately after Euromaidan, in the last two years, has finally received some international attention.[2] However, in the West, this deep transformation of Ukrainian center-periphery relations sometimes still is seen as being mainly driven by foreign factors, such as Kyiv’s Association Agreement with the EU or the Minsk Agreements with Russia. The internal origins of the ongoing, and already partly successful, reform are often insufficiently appreciated, and even wholly misunderstood.

Domestic demand for genuine decentralization, however, has been present ever since Ukraine’s independence. Thus, the ongoing reform benefits from previous domestic lessons, as well as from generous Western developmental support.[3] The dynamic story of post-Euromaidan decentralization is the result of lessons from earlier, and often failed, attempts to devolve power to the local level. Substantial institutional change was formerly constrained by a lack of political will, or of evidence-based expertise. After the victory of the Euromaidan Revolution in 2014, these two missing components finally coalesced.[4]

What Was Wrong in Ukraine’s Center-Periphery Relations?

Noteworthy previous reform efforts aimed at improving multi-level governance and introducing more meaningful self-government in Ukraine are among the historic roots of post-Euromaidan decentralization.[5] Certainly, these earlier attempts were largely unsuccessful. Yet they are informative not only for understanding the background and sources, but also the nature and chances, of current transitions in Ukraine’s post-Euromaidan political life.

Prior to the Euromaidan Revolution, Ukrainian policymakers competing for power and resources often exploited center-periphery relations in intra-elite struggles. Instead of designing and implementing either decentralization or centralization for the sake of improving public policies and promoting regional development, political factions tried to shift institutional prerogatives for the benefit of competing interest groups, often with particular regional affiliations. As a result, Ukraine was, by early spring 2014, still a formally centralized state with administrative and territorial structures largely inherited from the USSR.[6]

In March 2014, Russia illegally annexed Crimea and Sevastopol, and the Moscow-fueled conflict in the Donbas started shortly thereafter.[7] These events, while being instigated from outside,[8] also illustrated the vulnerability of the Ukrainian state’s regional and municipal structures.[9] The country suffered from a lack of territorial cohesion, large intra-national disparities, insufficient local self-government, and limited inter-communal cooperation—conditions that, while not alone sufficient to generate an armed uprising, certainly eased Russian meddling.[10]

Before 2014, institutional and financial opportunities and incentives to foster local development were modest. Sub-national self-governance remained weak and provided little room for development. In the 24 regions (oblasts) and 490 districts (rayons) of unitary Ukraine, only directly elected councils in villages, towns, and cities had the constitutional right to establish their own “executing organs” (vykonavchi orhany). Smaller towns and villages which elected councils and established executive committees, however, suffered, and often still suffer today, from too low institutional and financial capacity to properly provide basic services. They were, and partly still are, dependent on central state organs.

Directly elected councils in regions and districts so far have no constitutional rights to establish executive committees on their own. Thus, they delegate their decisions to executives appointed directly by the center. Accompanying weak self-government in regions and districts was a centrally imposed executive vertical designed to implement Kyiv’s decision-making across Ukraine. In practice, the prerogatives of the oblast and rayon councils, on the one side, and the central executive vertical, on the other, thus competed with, and still partly duplicate, one another.[11] This peculiar arrangement was the result of a compromise between the president and parliament in 1996, a reflection of the government’s effort to secure the loyalty of regional elites to the center.

At the local level, only certain so-called “cities of oblast significance” had enough power and resources to enjoy some genuine self-government. Their residents elected mayors and city councils that established executive committees and generated income for their municipal budgets. Although smaller towns and villages also elected councils that established executive committees, those areas depended on, and still partly rely on, financial transfers from Kyiv. Still, prior to 2014, there had already been some drives to support meaningful local self-governance.

First Decentralization Attempts

Pre-independence legacies of authoritarian and totalitarian governance have contributed to institutional resilience against early post-Soviet decentralization efforts in independent Ukraine. Enormous differences in the socio-economic development of regions and a lack of inter-regional cooperation both triggered and complicated several earlier decentralization drives. Most of them reflected power struggles either between the president and the parliament (in 1991–96), or between the president and the prime minister (in 2005–13).[12]

The very first attempt to introduce local self-governance occurred before Ukraine’s formal independence from the Soviet Union, and was aimed at decreasing the role of the Communist Party in local governance. Already on the eve of its full separation from Moscow, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic’s newly elected national parliament introduced a legislative framework on local self-governance. On December 7, 1990, it approved the law “On Local Councils and Local & Regional Self-Governance,” which allowed all directly elected councils to exert more power over their jurisdictions. It also made these councils responsible for carrying out functions of regional or local self-government.

Yet there was no clear distinction between the responsibilities of the center, on the one hand, and the duties of local governance, on the other. This was, moreover, not the key pitfall of the 1990 law. Its major negative repercussions paradoxically resulted from the excessive freedoms it provided to municipalities. The law allowed even very small villages to establish their own decision-making and executive organs.

As a result, soon after Ukraine gained independence in 1991, the number of self-governing units dramatically increased. In the early 1990s, there appeared around 10,000 self-administering local communities. Yet, with an average population of about 1,500 inhabitants, these municipalities were often far too small to provide even basic public services - not to mention to effectively promote local development. Such weak local self-governance was not yet a major issue because in early independent Ukraine, policymakers prioritized the regional (oblast) as well as district (rayon) levels of self-governance while often ignoring the municipal one. Local matters of public service delivery were—with some notable exceptions in certain dynamic cities—largely overlooked.

What followed was a mind-boggling back-and-forth in the provision and cancellation of prerogatives to regional and local governmental organs during the first decade of independence. These frequent shifts were, however, less the result of genuine concern for decentralization than of national political struggles between the presidents (Leonid Kravchuk and Leonid Kuchma) and the national parliament, which were competing with each other for power. In 1992, the law “On the Presidential Representative” and the new edition of the law “On Local Councils and Local & Regional Self-Governance” were approved. They abolished the just-created executive organs of the directly elected regional and sub-regional councils and introduced instead, as oblast and rayon executives, presidential representatives. These centrally appointed governors and district managers were in charge of implementing decisions from Kyiv and overseeing decision-making within the directly elected regional and sub-regional councils.

Two years later, however, parliament approved the law “On the Establishment of Local Power Institutions and Self-Government,” in 1994. This law again abolished regional executives and transferred their responsibilities back to executive committees appointed by elected regional and sub-regional councils. The 1994 law appeared to be a genuine attempt to strengthen self-government. Yet it provoked a largely chaotic regionalization and altogether failed to strengthen the capacity of the local governing bodies to deliver public services properly.

In 1995, the newly elected President Leonid Kuchma and national parliament signed a constitutional agreement. Among other provisions, this treaty converted the executive committees of the directly elected regional and sub-regional councils back into state administrations headed by officials appointed by the president. Subsequently, this mixed model became entrenched in Ukraine’s new 1996 constitution: directly elected oblast and rayon councils served as bodies of (sub)regional representation and decision-making, but centrally appointed regional and district state administrations fulfilled the executive function. These constitutional provisions also made clear that the president, and not the parliament, was responsible for managing center-periphery relations in the newly introduced presidential-parliamentary republic.

Alas, following its accession to the Council of Europe, Ukraine signed (in 1996) and ratified (in 1997) the European Charter on Local Self-Government. Under the new responsibilities of both its own 1996 constitution and the European Charter, Ukraine had to pass new domestic legislation that again re-defined the prerogatives of municipalities and specified anew the responsibilities of regional executives, in the 1997 law “On Local Self-Government in Ukraine” and the 1999 law “On Regional State Administrations.” These changes proved, however, insufficient to establish a sustainable model of multi-level governance. In practice, regional executives subordinated to the president continued to concentrate local power in their hands.

There were also noteworthy attempts to reform Ukraine’s territorial division and sub-national budgets. For instance, the 1998 Concept of Administrative Reform in Ukraine, approved by Presidential Decree No. 810, indicated an ambitious plan to introduce new forms of governance and divisions of territories. For various reasons, this Concept, however, failed to effect real policymaking. Its vague formulations left unclear the particular tasks and expected results of the suggested changes.

Due to a lack of consistent, comprehensive, and deep administrative reforms, bargaining between central and local actors continued. Inter-regional disparities did not decline, but rather sharpened further. Many organs of supposed self-government, with the partial exception of certain large cities, continued to depend heavily on transfers and subsidies from Kyiv, which were allocated in an often insufficiently transparent manner.

Precursors to the 2014 Decentralization Reform

While a coherent system of multi-level governance remained absent before the Euromaidan, an early attempt to reform the Budget Code of Ukraine was relatively successful. In 2001, Ukraine introduced a formula for regions, districts, and localities to certain parts of central budget allocations. This change improved the system of intergovernmental transfers, increased overall transparency in public finances and contributed to a gradual decline of bargaining.[13]

However, an attempt to proceed further with the transformation of center-periphery relations failed. The Law Draft 3207-1 contained a new fundamental reform attempt, submitted to parliament in 2003. It proposed a redefinition of the administrative-territorial structure of Ukraine via, among other things,

- An introduction of the concept of hromady (communities) instead of cities, towns, and villages,

- The subordination of regional executives to the Council of Ministers (thereby excluding the president from this part of intragovernmental relations), and

- The establishment of “executing organs” (vykonavchi orhany) appointed by elected regional and sub-regional councils.

Yet, due to severe tensions between outgoing President Leonid Kuchma and his opposition in 2003–04 - a confrontation eventually culminating in the Orange Revolution - the amendment failed to gain support.

Instead, during the 2004 electoral uprising, a far-reaching constitutional reform, known in Ukraine as politreforma, was negotiated between the governing coalition and opposition forces. This fundamental rearrangement of institutional power in Ukraine weakened the office of the president and introduced the current parliamentary-presidential republic where the prime minister formally holds almost as much power as the president and, in some ways, even more. Yet, this transition did not tackle the issue of decentralization.

The politreforma merely re-subordinated regional executives to both the president and the prime minister. It thereby created an additional source of confusion. The newly shared responsibility for (sub)regional state administrations had been expected to become an institutional stimulus for compromise and cooperation.[14] In reality, however, it became yet another field of competition between president and prime minister.[15]

After the triumph of the Orange Revolution in late December 2004, the post-revolutionary government finally included decentralization and a territorial remake of Ukraine among its reform priorities. A team led by new First Deputy Prime Minister Roman Bezsmertnyi designed and promoted, throughout 2005, a so-called “Concept of Administrative-Territorial Reform” that aimed to improve local governments’ capacity to provide services to citizens and to boost regional development. The draft Concept suggested introducing a three-level administrative-territorial system that would have consisted of

(a) territorial local communities (hromady) with no less than 5,000 residents;

(b) sub-regional districts (rayony) with no less than 70,000 residents, including so-called “cities-districts” for towns with more than 70,000 residents; and

(c) regions, including all oblasts, Crimea as well as Sevastopol, and so-called “cities-regions,” i.e., metropoles with no less than 750,000 residents.

According to this scheme—previewing changes that started in 2015—the existing smaller local communities would have to be fused in order to improve their capacity to provide basic services to residents. Bezsmertnyi’s Concept thus already explicitly linked the issue of a new administrative-territorial division of the state to its ability to deliver public services. It would have significantly reduced the number of rayons and increased their size. Moreover, rayons would have lost a significant share of their responsibilities due to the empowerment of new territorial communities emerging out of amalgamation of villages and towns.

The 2005 draft Concept highlighted the special role of cities, enlarging their budgets and delegating to them more responsibilities regarding service provision and local development. Moreover, the draft Concept suggested strengthening executive committees of regional and sub-regional councils, and drawing a clearer dividing line between their competencies and the centrally appointed regional executives.

Such radical changes, however, required further constitutional amendments. It also necessitated the adoption of up to 300 new laws—or so, at least, Bezsmertnyi then claimed.[16] But due to a lack of political will among central and regional stakeholders as well as to an absence of relevant draft laws, Bezsmertnyi’s ambitious plan fell, in the fall of 2005.

Instead, parliament approved the State Law on the Stimulation of Regional Development, and, in 2006, the State Strategy on the Stimulation of Regional Development. They provided institutional frameworks for identifying regional development priorities and allocating money for certain tasks. One of the instruments that they suggested were agreements signed by regional councils and the central government. In practice, such regional agreements did not serve their purpose of improving economic development. Instead, they quickly emerged as a battleground contested by oligarchs looking to promote their enterprises rather than the public interest of the respective regions and municipalities.

Darkness before Dawn

Post-Orange governments blocked, rather than advanced, changes in the division of power between the center and regions as well as municipalities and stalled a reform of Ukraine’s dated administrative and territorial architecture. The most telling case was the fate of the promising “Concept of Reforming Local Self-Government,” designed by the newly established Ministry of Regional Development and approved by the Cabinet of Ministers in July 2009. Supporting legislation at the time included a package of drafts for urgent laws, including amendments to the 1997 law “On Local Self-Government in Ukraine” and to the 1999 law “On Regional State Administrations,” as well as new drafts on the amalgamation of communities (hromady) and changes to the administrative-territorial division of Ukraine.

Despite the emergence of this comprehensive and concrete reform agenda, the Cabinet of Ministers did not hasten with its implementation. In 2009, this turned out to be a fateful omission. Soon, a new and very different political period, the presidency of Viktor Yanukovych (2010–14), saw a new concentration of power in Kyiv via a revival of the super-presidential and centralistic 1996 constitution.

One rare case indicating at least some commitment to regional interests in policymaking was the establishment of the Council of Regions in 2010. This organ constituted, however, only a consultative institutional platform for central political actors, regional executives, and the heads of regional councils, and functioned mainly as a transmission-belt for implementing the central government’s regional policies. The Council of Regions—while, perhaps, by itself a good idea—was not designed to promote genuine de-concentration of power.

In sum, Ukrainian policymakers’ promotions of decentralization were half-hearted and not particularly fruitful, before Euromaidan opened a new chapter in post-Soviet history. Still, these earlier attempts, their various failures, and the lessons learned were not entirely meaningless. These and similar experiences paved the way for a more successful, domestically driven, and externally supported decentralization reform that started in 2014.

Conclusions

Among the most successful post-Euromaidan transitions, are the fundamental changes to state-society relations resulting from decentralization. It gives ordinary citizens across the country a larger say in local political decision-making and public policy formation. So far, the reform has meant, above all, the creation and empowerment of new amalgamated territorial communities that receive novel prerogatives, resources, and responsibilities within, among others, a parallel sectoral decentralization.[17] The reform, moreover, is about to enter a new phase, announced by the government of Ukraine in January.[18] It foresees the amalgamation of Ukraine’s rayons (districts) as well as a strengthening of regional and sub-regional government via constitutional reform.

The already visible success of post-Euromaidan decentralization can be partly explained by the valuable lessons that civic activists and interested policymakers had learned while trying to introduce amendments to center-periphery relations in Ukraine before 2014. Why have these attempts been more successful in the last five years? Firstly, the degree of strategic controversy and political confrontation around the issue of decentralization has dropped. Most post-revolutionary policymakers agree with the necessity to introduce stronger local self-governance, and only contest the sequence as well as the pace of the proposed changes.[19] In contrast to the pre-Euromaidan period, policymakers now not only claim to support decentralization during electoral campaigns, but have implemented decisions to this effect once in office.[20]

Secondly, Ukrainian experts are now better prepared to address relevant domestic needs and circumstances when implementing decentralization, because they have learnt the bitter lessons of pre-2014 unsuccessful attempts to empower self-government and amend the administrative and territorial system of Ukraine. Today, effective policy development and implementation often results less from top-down administrative pressure than from bottom-up promotion of research-based solutions.

Thirdly, post-Euromaidan civil society has become strong enough to end central policymakers’ continued ignorance of the decentralization agenda. More effective policymaking has, since 2014, resulted from persuasive advocacy from civic activists.[21] Moreover, foreign donors have provided financial support and technical expertise for these campaigns.

Pre-Euromaidan attempts to promote decentralization in Ukraine not only generated valuable evidence-based domestic expertise on how (and how not) to reform center-periphery relations. Russia’s exploitation of the structural incoherence of the Ukrainian state also demonstrated that it is dangerous to neglect local governments and to fail to increase their authority.[22] The continuing post-Euromaidan decentralization’s remarkable broadness, growing sustainability, and increasing depth increases the likelihood that this reform effort will succeed, unlike previous attempts.[23] This should make Ukraine a more successful democracy in which stronger self-government leads to faster economic development and better public services.[24]

In view of Ukraine’s pivotal role in the post-Soviet space, its local governance reform also has a geopolitical dimension. Decentralization supports the Ukrainian state’s administrative capacity, general resilience, internal cohesion, and the young country’s pro-European course.[25] It may also play the role of a reform template for other former republics of the USSR on how to strengthen their own political stability.[26]

========================

Valentyna Romanova holds a BA, MA, and PhD in political science from the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. With more than 10 years of experience in academia and think tanks, she focuses on territorial politics, regional policy, and multi-level governance. Romanova is a senior consultant for the Department of Regional Policy at the National Institute for Strategic Studies and teaches within a joint German-Ukrainian MA program at NaUKMA. She has conducted, with a Chevening Scholarship, research on good governance regarding regional differences, and, with a Marie Curie Fellowship at the University of Edinburgh, work on territorial politics in Ukraine during the transition from authoritarian rule. Romanova is a co-editor of the “Annual Review of Regional Elections” issue of the journal Regional & Federal Studies. E-mail: vromanova@ukr.net

Andreas Umland, CertTransl (Leipzig), AM (Stanford), MPhil (Oxford), DipPolSci, DrPhil (FU Berlin), PhD (Cambridge), has held fellow- and lectureships at the Hoover Institution, Harvard’s Weatherhead Center, St. Antony’s College, Urals State University, Shevchenko University of Kyiv, Catholic University of Eichstaett, and Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. Since 2014, he has been a researcher at the Institute for Euro-Atlantic Cooperation in Kyiv, and, since 2019, a non-resident fellow at the Center for European Security of the Institute of International Relations in Prague as well as adjunct professor at the Friedrich Schiller University of Jena. He is the editor of the book series Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society and Ukrainian Voices published by ibidem-Verlag in Stuttgart, and distributed by Columbia University Press in New York. His publications focus on Russian and Ukrainian domestic and foreign affairs including radical nationalism, party politics, and international security.

E-mail: andreas.umland@uni-jena.de

Umland's work for this article benefited from support by "Accommodation of Regional Diversity in Ukraine (ARDU): A research project funded by the Research Council of Norway (NORRUSS Plus Programme)." See blogg.hioa.no/ardu/category/about-the-project/.

[1] Roger Myerson and Tymofiy Mylovanov, “Fixing Ukraine's Fundamental Flaw,” Kyiv Post, March 7, 2014, https://www.kyivpost.com/article/opinion/op-ed/fixing-ukraines-fundamental-flaw-338690.html; Editorial Board, “Decentralization: Second Try,” Vox Ukraine, July 16, 2015, https://voxukraine.org/2015/07/16/decentralization-second-try/; and Ivan Lukerya and Olena Halushka, “Decentralization as a Remedy for Bad Governance in Ukraine,” Euromaidan Press, December 5, 2016, http://euromaidanpress.com/2016/12/05/decentralization-governance-ukraine-reform/.

[2] For example, see Balazs Jarabik and Yulia Yesmukhanova, “Ukraine’s Slow Struggle for Decentralization,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 8, 2017, carnegieendowment.org/2017/03/08/ukraine-s-slow-struggle-for-decentralization-pub-68219; and Maryna Rabinovych, Anthony Levitas, and Andreas Umland, “Revisiting Decentralization After Maidan: Achievements and Challenges of Ukraine’s Local Governance Reform,” Kennan Cable, no. 34 (July 16, 2018), www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/kennan-cable-no-34-revisiting-decentralization-after-maidan-achievements-and-challenges; William Dudley, “Ukraine’s Decentralization Reform,” SWP Working Papers, no. 1 (May 2019), https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/arbeitspapiere/Ukraine_Decentralization_Dudley.pdf.

[3] For example, see Angela Boci, “Latent Capacity of the Budgets of Amalgamated Territorial Communities: How Can It be Unleashed?” Vox Ukraine, August 30, 2018, voxukraine.org/en/latent-capacity-of-the-budgets-of-amalgamated-territorial-communities-how-can-it-be-unleashed/; and Maintaining the Momentum of Decentralisation in Ukraine (Kyiv: OECD, 2018), www.oecd.org/countries/ukraine/maintaining-the-momentum-of-decentralisation-in-ukraine-9789264301436-en.htm.

[4] Jurij Hanuschtschak, Oleksij Sydortschuk, and Andreas Umland, “Die ukrainische Dezentralisierungsreform nach der Euromajdan-Revolution 2014–2017: Vorgeschichte, Erfolge, Hindernisse,” Ukraine-Analysen, no. 183 (2017): 2–11, http://www.laender-analysen.de/ukraine/pdf/UkraineAnalysen183.pdf.

[5] Among early seminal Ukrainian-language surveys were Anatolii Tkachuk, Mistseve samovryaduvannya ta detsentralizatsiya: Praktychnyy posibnyk (Kyiv: Sofiia, 2012); and Yuriy Hanushchak, Reforma terytorial’noi orhanizatsii vlady (Kyiv: DESPRO, 2012).

[6] Kyiv and Sevastopol are two Ukrainian cities with a special status acknowledged in the constitution and regulated by separate laws.

[7] Nikolai Mitrokhin, “Infiltration, Instruction, Invasion: Russia’s War in the Donbass,” Journal of Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society 1, no. 1 (2015): 219–250; Oleksandr Zadorozhnii, “Hybrid War or Civil War? The Interplay of Some Methods of Russian Foreign Policy Propaganda with International Law,” Kyiv-Mohyla Law and Politics Journal, no. 2 (2016): 117–128; and Andrew Wilson, “The Donbas in 2014: Explaining Civil Conflict Perhaps, but Not Civil War,” Europe-Asia Studies 68, no. 4 (2016): 631–652.

[8] Andreas Umland, “The Glazyev Tapes, Origins of the Donbas Conflict, and Minsk Agreements,” Foreign Policy Association, September 13, 2018, foreignpolicyblogs.com/2018/09/13/the-glazyev-tapes-origins-of-the-donbas-conflict-and-minsk-agreements/.

[9] Sergiy Kudelia, “Domestic Sources of the Donbas Insurgency,” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memos, no. 351 (2014), www.ponarseurasia.org/memo/domestic-sources-donbas-insurgency; Andreas Umland, “In Defense of Conspirology: A Rejoinder to Serhiy Kudelia’s Anti-Political Analysis of the Hybrid War in Eastern Ukraine,” PONARS Eurasia, September 30, 2014, www.ponarseurasia.org/article/defense-conspirology-rejoinder-serhiy-kudelias-anti-political-analysis-hybrid-war-eastern; and Sergiy Kudelia, “Reply to Andreas Umland: The Donbas Insurgency Began At Home,” PONARS Eurasia, October 8, 2014, www.ponarseurasia.org/article/reply-andreas-umland-donbas-insurgency-began-home.

[10] Ivan Katchanovski, “The Separatist War in Donbas: A Violent Break-up of Ukraine?” European Politics and Society 17, no. 4 (2016): 473–489; and Serhiy Kudelia, “The Donbas Rift,” Russian Politics and Law 54, no. 1 (2016): 5–27.

[11] The most prominent partial exception, in formal terms, was the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (ARC), where the directly elected regional parliament appointed the head of the regional government (i.e., the prime minister), who was then approved by the president of Ukraine, who appointed the ministers of the regional government, on the suggestion of the prime minister of the ARC. In practical terms, by February 2014, the regional government in ARC was largely represented by the so-called makedontsy. These were ministers lobbied, first, by former ARC prime minister Vasyl Dzharty from the Party of Regions and, later, by his successor Anatolyi Mohyliov from the same party, jokingly referred to as “Macedonians,” after Yanukovych’s Donbas home town Makiivka. For more on this, see Andrew Wilson, “The Crimean Tatar Question: A Prism for Changing and Rival Versions of Eurasianism,” Journal of Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society 3, no. 2 (2017): 1–46.

[12] Valentyna Romanova, “The Role of Centre–Periphery Relations in the 2004 Constitutional Reform in Ukraine,” Regional & Federal Studies 21, no. 3 (2011): 321–339.

[13] Jorge Martinez-Vazquez and Signe Zeikate, Ukraine: Assessment of the Implementation of the New Formula Based Inter-Governmental Transfer System (Atlanta, GA: Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, Georgia State University, September 2004), https://www.academia.edu/19727028/Ukraine_Assessment_of_the_Implementation_of_the_New_Formula_Based_Inter-Governmental_Transfer_System.

[14] Robert K. Christensen, Edward R. Rakhimkulov, and Charles R. Wise, “The Ukrainian Orange Revolution Brought More than a New President: What Kind of Democracy Will the Institutional Changes Bring?” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 38, no. 2 (2005): 207–230.

[15] Romanova, “The Role of Centre–Periphery Relations.”

[16] Roman Bezsmertnyi, “Derzhava, yak i budyvlya, pochynaet’sya z fundamentu,” Uryadovyi kur’er, April 22, 2005, http://crimea-portal.gov.ua/kmu/control/uk/publish/printable_article?art_id=15884111.

[17] Anatolij Tkatschuk, “Zur Dezentralisierung: Erfolge, Risiken und die Rolle des Parlamentes,” Ukraine-Nachrichten, January 26, 2017, https://ukraine-nachrichten.de/dezentralisierung-erfolge-risiken-rolle-parlamentes_4568.

[18] The Cabinet of Minister’s Decree “On Approving the Action Plan of a New Phase of Reforming Local Self-Government and the Territorial Division of Power in Ukraine in 2019–2021” issued on January 23, 2019 (№ 77-р), https://www.kmu.gov.ua/ua/npas/pro-zatverdzhennya-planu-zahodiv-z-realizaciyi-novogo-etapu-reformuvannya-miscevogo-samovryaduvannya-ta-teritorialnoyi-organizaciyi-vladi-v-ukrayini-na-20192021-roki.

[19] Ya. A. Zhalilo et al., Detsentralizatsiya vlady: Yak zberehty uspishnist’ v umovakh novykh vyklykiv? (Kyiv: NISD, 2018).

[20] Natalia Shapovalova, “Mühen der Ebenen: Dezentralisierung in der Ukraine,” Osteuropa 65, no. 4 (2015): 143–152.

[21] Oesten Baller, “Korruptionsbekämpfung und Dezentralisierung auf dem Prüfstand des Reformbedarfs in der Ukraine,” Jahrbuch für Ostrecht no. 2 (2017): 235–268.

[22] Hennadiy Poberezhnyy, “Detsentralizatsiya yak zasib vid separatyzmu,” Krytyka no. 11 (2006): 3–7, http://krytyka.com/ua/articles/detsentralizatsiya-yak-zasib-vid-separatyzmu.

[23] Tony Levitas and Jasmina Djikic, Caught Mid-Stream: “Decentralization,” Local Government Finance Reform, and the Restructuring of Ukraine’s Public Sector 2014 to 2016 (Kyiv: SIDA-SKL, 2017), http://sklinternational.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/UkraineCaughtMidStream-ENG-FINAL-06.10.2017.pdf.

[24] Ruben Werchan, “Dezentralisierung: Der Weg zu einer effizienteren Regierung, Wirtschaftswachstum und dem Erhalt der territorialen Integrität?” in Evgeniya Bakalova et al. (eds.), Ukraine–Krisen–Perspektiven: Interdisziplinäre Betrachtungen eines Landes im Umbruch (Berlin: WVB, 2015), 187–212.

[25] Mykola Rjabcuk, “Dezentralisierung und Subsidiarität: Wider die Föderalisierung à la russe,” Osteuropa 64, nos. 5–6 (2014): 217–225.

[26] Andreas Umland, “International Implications of Ukraine’s Decentralization,” Vox Ukraine, January 30, 2019, voxukraine.org/en/international-implications-of-ukraine-s-decentralization/.

Authors

Analyst, the Stockholm Centre for Eastern European Studies at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs

Kennan Institute

The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region though research and exchange. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

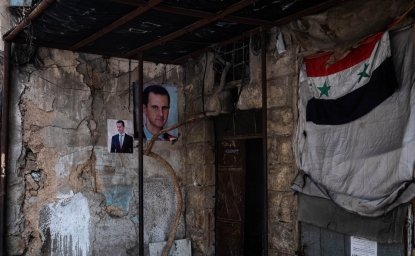

Assad's Reign Ends: Rebel Forces Overthrow Decades-Long Rule in Syria

Любовь до гробовых