189. Europe and U.S. Relations 10 Years After the Fall of the Berlin Wall: A Retrospective

A decade later, the events of 1989 have lost none of their capacity to astonish. The sheer possibilities open at that time are enough to baffle even the knowledgeable observer. For those of us who lived through these events as they happened and had a certain role in shaping them, the enormity of what transpired that fateful year becomes even more amazing with the passage of time.

Looking back on the historic events of 1989, especially the events leading up to the unification of Germany, proves more than ever that history cannot be pre-determined.

With the adoption of the March-April 1989 Polish Roundtable Agreement which promised free and fair elections that summer, America recognized the unique opportunity to end communism in Poland. And if communism ended in Poland, it meant the beginning of its demise everywhere in Eastern Europe, including the G.D.R., which brought the German Question to the forefront of the West's agenda, whether the world was ready for it or not.

Throughout this domino process, the role of U.S. leadership proved to be the necessary catalyst enabling the possibility of German unification and, in turn, the beginning of the end for communism and the Cold War. It is important to distinguish that American leadership was required not to ensure German unification - that was a process driven internally, from below - but to ensure that the process came out right by creating an international environment conducive to its success. Yet, though the Administration recognized the historic chance and seized the opportunity, despite its less than obvious character at the time, it overestimated the amount of time needed for the disintegration of the Warsaw Pact, judging the crumbling process to be a matter of years, not months.

This overestimation by the international community proved to be partially the result of a lack of clear focus and direction in American leadership. U.S. leadership had to first be developed, not simply asserted and, to the credit of the Bush Administration, it recognized the need for the creation of preconditions such as bi-partisan cooperation and governmental coherence required for the kind of leadership needed to enable peaceful and democratic change in Central and Eastern Europe. Furthermore, the Atlantic Alliance was also suffering from a period of disarray and lack of coherence. With grudging acceptance of self-determination by the Soviets and the uncertain, incoherent reaction from Western Europe, Alliance cohesion was paramount to ensuring the possibility for change in Eastern Europe.

The fact that the U.S. did recognize the need for action and threw its weight behind the Polish and Hungarian efforts for democratic change at a time when the choice was less than obvious and the rest of the international community was in favor of waiting for events to unfold, was in my estimation, the most important thing America did in helping bring about the end of the Cold War. This action implied the correct judgement that the Cold War began in and was about Eastern Europe, hence this was the place where it must end.

Over the next few years, the U.S. lost this clear direction and strategic focus when dealing with Eastern Europe, something that unfortunately was never again rebuilt. The scope and speed of these momentous changes are partially to blame. For Americans, the loss of focus at the end of the Cold War was accentuated by the manner in which it ended - without military victory, demobilization and celebration, without a certain date and sense of finality but with the unexpected capitulation of the other side without a shot being fired.

America's focus on close U.S.-German relations which it considered central to strategic national interests in the region, also played a role, leading to extravagant exaggerations and expectations for bilateral relations after Germany's unification and, in turn, resulting in the neglect of other key relations in Europe (i.e. France) and a total dismissal of the signs of approaching Yugoslav disintegration. Despite international outcries at America's "unrealistic" determination to secure a united Germany in NATO, the U.S. stubbornly backed its original decision, primarily due to its concern over its future role in a Europe increasingly self-absorbed with its own integration. The judgement was that America's role in Europe transcended the Cold War; it was the factor of stability in Europe and NATO was the vehicle to ensure its involvement. By backing a united Germany in NATO, the U.S. was attempting to preserve NATO and thereby ensure its active involvement in the future of Europe.

America did succeed in transforming Germany from a "net importer of stability" to an actual factor of stability in the heart of Europe. In emphasizing the role of Germany in Europe however, the U.S. alienated other former traditional Western partners, adding to historic intra- European hostilities. On a positive note, the focus of the U.S. in Europe over time gave way to a more normal, healthier set of diversified relations with the rest of its Western partners.

In its zeal to preserve NATO however, America undermined certain European efforts to build a Common Foreign and Security Policy as well as the full development of other institutions which might have been better suited to the task of integrating the post-communist states of Eastern Europe. Consequently, despite recent NATO enlargement to the east and reluctant European Union commitment for similar accession eastward, the de facto division of Europe will persist longer than originally expected.

The end result of American focus on a unified Germany and preserving NATO at all costs was the failure of the United States and its Western European partners to fashion a new transatlantic balance of roles and responsibilities to carry the international order into the next century and hence, their inability to deal in a coherent manner with crises erupting in the Balkans as well as with the disintegration of the Soviet empire. The collapse of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia were far from our strategic radar in 1989. America foresaw the logic leading to the self-liberation of Eastern Europe, the unification of Germany, even the liberation of the Baltic states because these processes all fit in the Cold War frame of reference. What we failed to see was the prospect for the disintegration of the last of the multiethnic empires because this logic came from a different period of history - from the break-up of empires at the turn of the century. By approaching these events with a Cold War perspective, obvious signs were missed. And because we were not prepared to deal with events of such magnitude and insisted on approaching the rapidly disintegrating Soviet Union in a similar manner to Eastern Europe - as former Secretary James Baker asserted: "to bring democracy to a people who have never experienced it" - we started off on the "wrong foot" with Russia and the post-Soviet states. What the international community refused to recognize was that the chance for democratization in Russia belonged to the Russian people alone and to pretend that the U.S. and NATO had the power to bestow such gifts has led to the current backlash in Russia-West relations and the increasingly eroding domestic support for any Russia policy.

Similarly, despite superficial progress made in the enlargement of NATO to include three new East European members (Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic) and its halting adaptation to new strategic purposes in Bosnia and Kosovo, beneath the surface, the Alliance suffers more and more from a hallowing out process. The Europeans seemingly take for granted their relation with NATO, concentrating their energies instead on the European integration process. Simultaneously, the Alliance struggles for its self-preservation and definition as each new challenge becomes a litmus test for its survivability. In the process, the U.S. consistently shoulders most of the burden, leading to increasing questioning by the American public as to the need for such a burden.

Unfortunately, given the exaggeration of America's global leadership, the United States has yet to limit its visionary policy objectives to those on which it has the actual capacity to deliver. At the start of the twenty-first century, America is faced with the prospect of a more confused world order than ten years ago. Somewhere in the last ten years, America lost its strategic focus, its interest in the region becoming driven by short-term assessments instead of a longer, broader vision. The stop-gap measures employed in Bosnia and Kosovo most clearly bear witness to this shift in leadership policy. The U.S. continues to assert a level of leadership that its public is not willing to shoulder. Some policy figures in the current Administration believe that the U.S. has a unique responsibility to fashion a new global order. I myself, doubt it. This kind of misreading of America's place in history may lead to the pursuance of policies which are vastly in excess of our capabilities. Domestic preconditions do not exist for creating this kind of broad leadership and I do not see any immediate prospects for creating such preconditions.

Among the most important lessons to be drawn from the last decade is the necessity for more manageable objectives and a more detached view of how America might assist in the self-liberation and the long struggle for self-consolidation of democracy in Russia, the Balkans and the rest of Eastern Europe. America needs a more subtle foreign policy which would articulate a vision of a future that is more modest but more sustainable, generating at least the basic level of domestic public support and the basic level of bi-partisan agreement needed to carry out the clear-sighted kind of international leadership position the U.S. enjoyed in 1989.

Ambassador Hutchings spoke at an EES Noon Discussion on November 10, 1999 on the occasion of the 10th Anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall

Author

Professor of Public Affairs and Walt and Elspeth Rostow Chair in National Security, Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, University of Texas at Austin

Global Europe Program

The Global Europe Program is focused on Europe’s capabilities, and how it engages on critical global issues. We investigate European approaches to critical global issues. We examine Europe’s relations with Russia and Eurasia, China and the Indo-Pacific, the Middle East and Africa. Our initiatives include “Ukraine in Europe”—an examination of what it will take to make Ukraine’s European future a reality. But we also examine the role of NATO, the European Union and the OSCE, Europe’s energy security, transatlantic trade disputes, and challenges to democracy. The Global Europe Program’s staff, scholars-in-residence, and Global Fellows participate in seminars, policy study groups, and international conferences to provide analytical recommendations to policy makers and the media. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

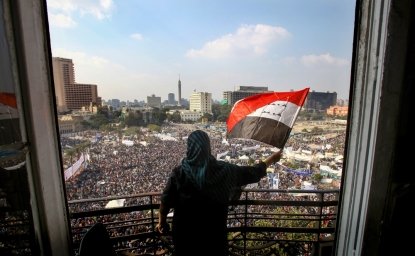

Living Interesting Lives: Daily Life Amidst Coup D’etat and Revolution