When the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) celebrated the 100th anniversary of its counterintelligence branch in May 2022, the Russian Postal Service released a collection of stamps that featured the leaders of Soviet counterintelligence. One of the individuals depicted was Pyotr Fedotov (1900-1963), who played a key leadership role in Soviet state security in its most infamous period from the late 1930s to the mid-1950s.

The general outline of Fedotov’s Chekist career has been known since the 1990s and is presented in Petrov and Skorkin’s well-researched reference guide Those Who Led the NKVD, 1933-1941.[1] I have also discussed Fedotov in my article “An Inside Look at Soviet Counterintelligence in the 1950s,” published by the Wilson Center in May 2023.[2]

Having started his Chekist career in the North Caucasus in the early 1920s, Fedotov rose to the top of the NKVD during the time of the Great Purge (1937-1938) and is known to have taken part in brutal interrogations and forgeries involving Stalin’s imaginary enemies. He was first made the head of counterintelligence in September 1939 and held that position throughout World War II. As a reward for his WWII efforts–which involved mass-scale, egregious violations of human rights–Fedotov was briefly put in charge of the intelligence branch of Soviet state security in the immediate post-war period (September 1946-May 1947). He returned to take the reins of counterintelligence in March 1953 and stayed on when the Committee for State Security (KGB) was founded in March 1954. A small portion of his crimes came back to haunt him in 1956, a period of relative openness in Soviet public life thanks to Khrushchev’s anti-Stalinist policies. At that time, Fedotov was reported to have supervised a devious operation involving a fake border post near Khabarovsk in the Russian Far East designed to terrorize the suspected critics of the Soviet regime in the 1940s.[3] The report of this operation, produced by the Soviet Communist Party Administrative Control Committee, made it to the Politburo, which removed Fedotov from the top KGB counterintelligence position (the head of the Second Chief Directorate) and demoted him to an insignificant position at the Higher School of the KGB.[4] In 1959, during the “house cleaning” efforts initiated by the new KGB Chairman Aleksandr Shelepin, Fedotov was fired from the KGB, stripped of his general’s rank, and expelled from the Communist Party. The official charge against him was “violations of legality during the Stalin Era.”[5] Unlike many of his innocent victims, however, he died a free man in 1963.

Given Fedotov’s biography, it is clear why the FSB has been reluctant to declassify any archival documents related to his operational activities. Having those documents available for public scrutiny would puncture and dissolve the image of Fedotov as a praiseworthy servant of the Soviet state that the 2022 Russian stamp honoring him seeks to project.

However, there are documents concerning the activities of Soviet state security that are out of the control of the FSB and Putin’s Russia, such as the Lithuanian KGB files housed

in the Hoover Institution at Stanford University.[6] On a recent research visit to Hoover, I discovered a hitherto unknown document written by Fedotov in 1940 which reveals not only his personal leadership style and operational approach, but also the sources and methods of Soviet counterintelligence during that period.[7]

Here, I provide a close reading and analysis of this document, framing it as a means of countering the ongoing revisionism in Putin’s Russia regarding Stalin’s rule in general and the work of Soviet state security (the Chekists) in particular.

Raising the Curtain on Soviet Counterintelligence in 1940

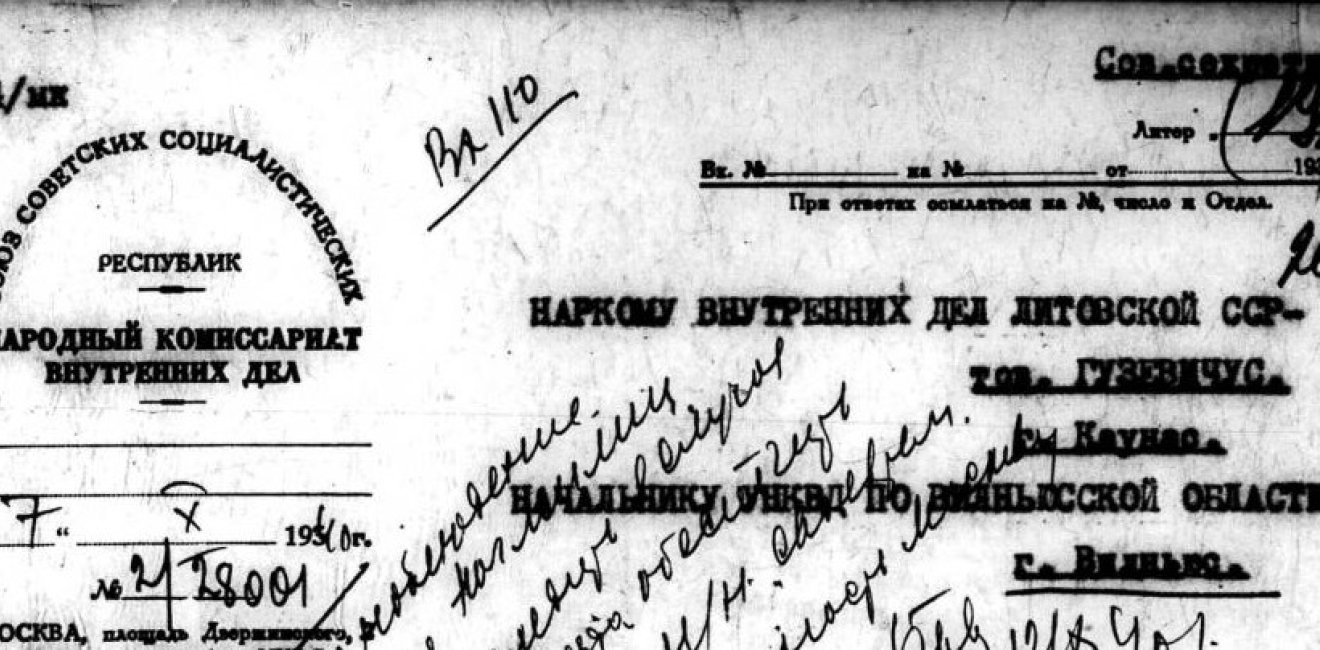

The document in question is a letter consisting of 6 typed pages. Written on the official stationery of the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD), the letter is numbered 2/ 28001 and dated October 7, 1940.[8] It is addressed to the People’s Commissar of the Internal Affairs (NKVD) of the Lithuanian SSR Aleksandr Guzevičius[9] based in Kaunas and the unnamed head of the Directorate of the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD) for the Vilnius region based in Vilnius. The Soviet Union had completed its annexation of Lithuania by early August 1940. The fact that Guzevičius was in Kaunas and that Fedotov was unaware of the name of the person in charge of the Vilnius NKVD suggests that the Soviet state security administration in

Lithuania was in the state of flux at that time. The center of operations was apparently still in Kaunas, the post-WWI temporary Lithuanian capital, rather than in Vilnius. This would soon change with the transfer of all major government institutions to Vilnius.

Fedotov began the letter in media res, displaying his direct, unmediated style of communication and reflecting the attitude of a superior officer speaking to his subordinates. He informed Guzevičius and the unnamed head of the Vilnius NKVD about four different cases that he wanted them to take immediate action on. He warned them that the NKVD assigned high priority to these cases and asked them to “personally ensure that proper actions are taken and report directly to [him] about the outcome.” There was no mistaking Fedotov's tone: the Lithuanian NKVD chiefs' own jobs were on the line if something went wrong.

The first case involved the so-called “traveling agent“ of the Soviet NKVD who had passed through Kaunas and Vilnius in September 1940.[10] It appears that this agent, who remained unnamed, was connected to the Catholic and, more specifically, Jesuit milieu because Fedotov recounted the agent's meeting with the former student of the Dubno Jesuit Seminary[11] Vladislav Solovei in Vilnius.[12] Fedotov stated that Solovei, whose full name he filled in by hand in order to hide his identity from the secretarial pool, told the agent that he intended to apply for an exit visa, ostensibly to go to Lviv in search of employment, but, in reality, to try to cross into Hungary and Italy with Rome as the final destination. Fedotov then cautioned his addressees that any measures taken against Solovei by the Lithuanian NKVD, including the denial of an exit visa, would throw suspicion on the NKVD agent who received the exit visa without any problems. Consequently, Fedotov asked the Lithuanian NKVD to issue Solovei the exit visa promptly when he applied for it in either Kaunas or Vilnius.

At the same time, Fedotov instructed the Lithuanian NKVD to place Solovei under surveillance until his arrival in Lviv, where they were to hand the surveillance over to the Lviv branch of the NKVD. This shows that the NKVD had an established practice of inter-regional cooperation on operational matters and that it was nothing extraordinary for the officers of one branch to travel on assignment to the jurisdiction of another branch, even if this involved two different Soviet republics. Presumably Fedotov would also have notified the NKVD branch in Lviv about this arrangement, the confirmation of which could be sought in the Ukrainian NKVD archives.

However, the key point in Fedotov's letter regarding the NKVD counterintelligence approach to Solovei (and to other individuals who had been placed in the category of suspects by the NKVD) came at the very end. Fedotov revealed that “we intend to arrest [Solovei] when he attempts to cross the border [presumably, the border between Ukraine and Hungary], and, depending on his behavior during the interrogation, decide the question of his recruitment.“ Here was a description of one of the methods that the NKVD counterintelligence used to recruit agents: the suspected individuals were arrested and put under physical and psychological pressure during the interrogation. For those who refused to collaborate, the only option left was imprisonment, or worse.

In Solovei’s case, the archival documents chronicling his later fate were not found in the file containing Fedotov’s letter. Therefore, many questions remain, including whether or not he survived WWII. However, the fact that the NKVD counterintelligence was interested in recruiting him, while aware of his intention to go to Rome, demonstrates that one of the top NKVD requirements at that time was to penetrate Catholic clergy circles in the Vatican.

The second case mentioned by Fedotov was the case of Anthony Dombrowski (Антоний Домбровский), described as the head of the Jesuit Mission in Poland before the German invasion in 1939. According to Fedotov, Dombrowski lived in the village of Shavli near Kaunas.[13] Fedotov stated that although the already mentioned NKVD “traveling agent” did not get a chance to meet with Dombrowski in person, he heard from his acquaintances in the Jesuit communities in Kaunas and Vilnius that Dombrowski was “terribly frightened” and even prepared “to quit priesthood” in order to avoid getting imprisoned by the NKVD. Fedotov cynically emphasized that this made Dombrowski an ideal candidate for recruitment and therefore should be made use of by the Lithuanian NKVD. He insisted that Guzevičius and the unnamed head of the Vilnius NKVD immediately send “an experienced operative” to Shavli to “check on” Dombrowski and initiate the process of his recruitment. Thus, in the case of Dombrowski, just as in the case of Solovei, we see the NKVD counterintelligence brutally manipulate the genuine human fear of suffering and death and the desire for survival in order to recruit agents for their operational tasks. Unfortunately, I was unable to locate any documents regarding Dombrowski’s later fate.[14]

The third case from Fedotov’s letter involved Franz Helvegel (Франц Гельвегель) described as a priest of the Eastern Catholic Church (“not a Jesuit,” as Fedotov emphasized to his addressees). According to Fedotov, the NKVD “traveling agent” had a lengthy conversation with Helvegel in Kaunas. A citizen of the Netherlands, Helvegel told the agent that he did not intend to return to his native land, which, at that time, was under the German occupation, because he “hated Germans so much.” Helvegel further confided to the NKVD agent that he had written to the headquarters of the Eastern Catholic Church in the Vatican asking for permission to offer some of his “inventions” to the Soviets in order to obtain a more favorable treatment for his activities in Lithuania.[15] However, he received what he described as “a brutal and rude negative reaction,” which, according to the agent, did not dampen Helvegel’s initial enthusiasm for contacting the Soviets. The agent also added that Helvegel was academically engaged in studying the classics of Marxism but that he disagreed with what he called “[Marxist] anti-religious propaganda” which, of course, was hardly surprising for somebody who was a priest. Overall, however, the agent was convinced that Helvegel made a suitable candidate for recruitment.

What followed were Fedotov’s detailed instructions to Guzevičius and the Vilnius NKVD chief on how to approach Helvegel’s recruitment which, according to him, due to Helvegel’s position, had to be “carefully prepared and gradually developed.” The instructions reveal the chess-like nature of some of the NKVD counterintelligence tactics which, in this case, involved two interdependent moves. As the first move, Fedotov instructed his addressees to have Helvegel report to the Kaunas police station under the pretense of having his passport checked. Once there, he was to be paired with an experienced operational officer who, acting as a police official, would broadly inquire about Helvegel’s future plans and gradually lead the discussion to the topic of new inventions. According to Fedotov, this would provide a “spontaneous” opening for Helvegel to tell the officer of his idea of sharing his inventions with the Soviet government. The officer would then pretend to be surprised but vaguely interested and would offer Helvegel to introduce him to another official who could be of more assistance with that.

In Fedotov’s set-up, this would constitute the second move. The second official who, according to Fedotov, should “preferably be an engineer” would play the role of a scientifically well-informed and friendly conversation partner. He would endeavor to become a close acquaintance of Helvegel and get him to open up more fully. At the same time, he would genuinely work to advance the cause of Helvegel’s inventions with the Soviet government and industry officials. As Helvegel would begin seeing that he was being taken seriously by the Soviet authorities, the second official, now a friend, would slowly, using the principle of reciprocity, try to get Helvegel to provide him with the information of interest to the NKVD. It was only after all this played out that, according to Fedotov, the question of Helvegel’s actual recruitment as an agent would be decided. Unfortunately, the archival materials available at this time do not shed any light on whether this priest, a citizen of the Netherlands, who seemed to have been an idealistic humanitarian at heart, eventually became the NKVD agent.

The last case mentioned by Fedotov in his letter concerned three nuns named Anna Strashek, Olga Yankovskaya, and Kseniya Karpovich[16] who were the residents of the town of Narva in Estonia. Apparently displaced and now living in Kaunas, they had applied for official permission to move to Vilnius for work. However, as the “traveling agent” reported to Moscow, their application had thus far received no response from the Lithuanian NKVD authorities. In his own case, however, the authorities had acted quickly and issued him the necessary permission. Concerned that this state of affairs could compromise the NKVD agent in the Catholic milieu in which he was operating, Fedotov instructed Guzevičius to grant the permission to the three nuns as soon as possible. Importantly, he also stated that he would inform the Estonian NKVD of the nuns’ movement, thus confirming the point made earlier that the NKVD took steps to ensure the efficient functioning of inter-regional and inter-republican counterintelligence cooperation.

***

This relatively short, hitherto unknown letter written by the head of the NKVD counterintelligence Pyotr Fedotov in 1940 offers a direct insight into the manipulative methods of the NKVD agent recruitment at that time. Ordinary individuals, Soviet and foreign citizens, were treated as disposable playthings and were physically and psychologically pressured and abused if that suited the interests of the NKVD. Fedotov may have gotten his likeness on a stamp as an official hero in the revisionist system of Putin’s Russia, but archival documents like this letter reveal the extent of his cynical and willful violations of basic ethical principles and moral norms.

[1] N. V. Petrov and K. V. Skorkin. Кто руководил НКВД, 1934-1941: Справочник [Those Who Led the NKVD, 1934-1941: A Reference Guide]. Moscow: Memorial, 1999, pp. 499-500. For an inexplicable reason, Petrov and Skorkin refer to Fedotov not as Pyotr but as Pavel. This is one of the very few errors in their otherwise excellent publication.

[2] Filip Kovacevic, “Soviet Counterintelligence in the mid-1950s: An Inside View Based on New Archival Research,” Cold War International History Project Working Paper No. 96, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars (May 2023), https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/inside-look-soviet-counterintelligence-mid-1950s.

[3] For a more detailed description of this operation, see Filip Kovacevic, “’An Ominous Talent’: Oleg Gribanov and KGB Counterintelligence,” International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence 36, No. 3 (2023), p. 791. For a similar operation run by the Czech Communist state security service, see Igor Lukes, “KAMEN: A Cold War Dangle Operation with an American Dimension,” Studies in Intelligence 55, No. 1 (2011), pp. 1–13.

[4] This report remained classified for the general public until the early 1990s.

[5] Petrov and Skorkin, Кто руководил НКВД, 1934-1941, p. 499.

[6] Lietuvos TSR Valstybės Saugumo Komitetas [Lithuanian KGB] Selected Records, Hoover Institution, https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt2n39r888/. Accessed on August 20, 2023.

[7] I gratefully acknowledge the Hoover Institution Library & Archives as an essential resource in the development of these materials. The views expressed in this publication are entirely my own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the fellows, staff, or Board of Overseers of the Hoover Institution.

[8] The letter is included in the agent network file codenamed JESUITS produced by the Secret-Political Department of the Vilnius Municipal Directorate of the NKVD of the Lithuanian SSR. The file contents were described by the Lithuanian archivists as referring to “the members of the religious community of the Polish Jesuits suspected of ties with foreign intelligence services.” Fond K-1, Op. 45, File 774, pp. 192-197. Lietuvos TSR Valstybės Saugumo Komitetas [Lithuanian KGB] Selected Records, Hoover Institution.

[9] Aleksandr Guzevičius (1908-1969) was the leader of the Lithuanian Communist Party in the 1930s. He was arrested by the Lithuanian police in 1932 and spent several years in prison. After the Soviet takeover of Lithuania in 1940, he was appointed to the position of the head of the Lithuanian NKVD. He withdrew with the Soviets in the summer of 1941 after the Nazi invasion. Guzevičius returned to Lithuania in 1944 and resumed his duties as the head of the NKVD. He survived the assassination attempt in August 1945 but was severely wounded and had to resign from the NKVD due to health reasons. He turned to literature and published several novels, receiving the prestigious Stalin Prize in 1951. In the mid-1950s, Guzevičius headed the Lithuanian Ministry of Culture. See “Biography of Aleksandr Guzevičius,” https://shieldandsword.mozohin.ru/personnel/guzevicius_a_a.htm. Accessed on August 20, 2023.

[10] Even when the agent was a woman, the NKVD typically used the male pronouns. The NKVD used “traveling agents” as liaisons and couriers between the different members of their agent networks. They were often veterans of the service and therefore extra efforts were made to ensure their safety as Fedotov’s letter demonstrates.

[11] On the history of the Dubno Seminary, formally known as the Papal Eastern Seminary, see Fr. Jerzy Zając, “The Genesis of the Papal Eastern Seminary in Dubno and Its Patrons,” Seminare 37, No. 4 (2016): pp. 163-176. The Seminary operated from 1931 to 1939. At that time, Dubno was a part of Poland.

[12] The file includes the undated autobiography of Solovei written by him as a part of his application to the Papal Eastern Seminary with a note that it was translated from Polish, Fond K-1, Op. 45, File 774, pp. 187-188. The fact that the NKVD had access to this document means that its officers had seized the archives of the Papal Eastern Seminary and were using them for their operational purposes.

[13] Shavli in Russian is typically translated as Šiauliai in Lithuanian. However, Šiauliai is one of the largest towns in Lithuania and is about 150 km from Kaunas. In the letter, Fedotov referred to “a village of Shavli near Kaunas.” Therefore, either there was a village called Šiauliai near Kaunas, or Fedotov was misinformed about the geography of Lithuania. Considering that Fedotov was unaware of the name of the head of the Vilnius NKVD, it could easily be the latter.

[14] There is no digitized information regarding his biography in either English or Russian.

[15] Fedotov did not mention any specifics regarding Helvegel’s “inventions.” What they were remains unknown.

[16] Their names were typed and not filled in by hand as in the three other cases indicating that their identity was less of a concern to the NKVD.