Wilson Center Editor's Note: This article and interview was first published by Dimitry Goncharov on the Russian-language dissident website Republic.ru on July 31, 2024. It was translated into English by Alexander V. Pantsov.

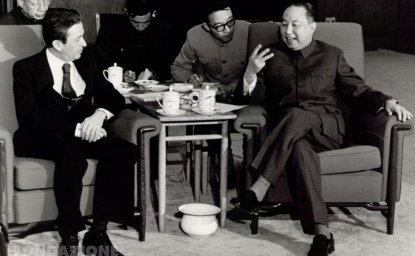

Aleksandar Novačić (b. 1939) is a renowned Serbian journalist and writer. He lived in China for fourteen years in the 1970s-90s and in the USSR/Russia for over ten years. He has written nineteen books on international politics, history, culture and literature, including eight on China. While he is not a China scholar by training, he has nevertheless been able to see more of China than many of his Chinese-speaking colleagues. He currently lives in Belgrade. - Dmitry Goncharov and Alexander V. Pantsov

Hu Yaobang, General Secretary of the CPC Central Committee in 1980-87 and Chairman of the CPC CC in 1981-82 was a ‘black sheep’ among the top Chinese leadership due to his openness to the ideas that did not accord with the official political line.

In early 1980, at one of the receptions at the Czechoslovak Embassy in Beijing, I was approached by Wang, my Chinese friend from the Xinhua News Agency. This time Wang acted as a mediator. After questioning whether I was really going back to Belgrade soon, he suddenly asked me why I should not ask for an interview with a high-ranking Chinese politician. According to him, I might get some interesting answers. I asked him if he had any suggestions and immediately got an answer: Hu Yaobang, General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China.

Somewhat dumbfounded, I returned to the press corps office. Unlike me, my translator Mr. Xi (at that time I still addressed him as “Comrade Xi”) was not surprised by this news. It was as if he, too, had expected something like this. Xi drafted a letter requesting an interview, and Chang, the chauffeur of the Tanjug News Agency corps, took the letter to the Information Department of the Chinese Foreign Ministry.

The reply did not have to wait for long. A few days later, which was an extremely short time in communicating with Chinese official institutions, I received a reply: The General Secretary of the CPC Central Committee invites all three Yugoslav correspondents permanently accredited in Beijing for an interview. The meeting place is Zhongnanhai!

I immediately passed this message on to my colleagues: Dragan Rancic, correspondent of the Belgrade newspaper Politika, and Tomica Butorac, correspondent of the Zagreb newspaper Vesnik. All three of us were not only surprised but also excited. We could not remember ever hearing of a foreign journalist recently being received in Zhongnanhai, that part of the Forbidden City where top Chinese politicians lived in their mansions inherited from the imperial times. We knew that the famous American journalist Edgar Snow had been there, and there was a relevant section in his book, The Long Revolution – “Breakfast with the Chairman.” But that had been ten years ago, on December 10, 1970. [Translator's note: Edgar Snow, The Long Revolution (New York: Random House, 1971), 165-176.]

We were also thrilled because Hu Yaobang was an extraordinary political figure. He was born into a rural family, ran away from home at thirteen to join Mao Zedong’s guerrillas, and at fourteen joined the Communist Party. He was one of the youngest participants in the 1934-35 Long March and after the war and the foundation of the People’s Republic of China, from 1953 to 1966, headed the Chinese New Democratic (since 1957 – Communist) Youth League, that was suppressed in the beginning of the “Cultural Revolution.” His patron was Deng Xiaoping who brought him back to the political life after Mao’s death.

Not a few Chinese politicians have gone through similar ordeals but Hu Yaobang was extremely open to the ideas that did not comport with the official pollical line. Foreign diplomats in Beijing spoke of his eccentricity. For example, sometimes at official dinners he would order that French rather than Chinese food be served, or that chopsticks be replaced by forks. We, Yugoslav correspondents, were interested in his life and his ideas. We didn’t know what to expect and how Hu would answer our questions.

He met us in front of his villa in Zhongnanhai, a beautiful lakeside pavilion. He was dressed in the simplest of Chinese Mao-style uniform, and I got an impression that it had been faded too much with numerous washings. Hu greeted us warmly, and I was surprised by the firm handshake of this sixty-four-year-old man who was only 5.1 feet tall. A fragrant jasmine tea was already prepared in the shade of the villa. Thus began our meeting with the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, which lasted almost six hours.

We also had lunch there: we were served simple Chinese dishes; of course, along with chopsticks. Afterward, Hu Yaobang took us on a walk around Zhongnanhai, showing us where Mao Zedong lived and where Zhou Enlai lived. He also showed us the villa where Deng Xiaoping lived with his family. According to him, Deng was kicked out of Zhongnanhai during the “Cultural Revolution” and never went back there. “That’s the way it should be,” Hu said.

What did we talk about? There was no specific topic. We switched from foreign to domestic politics and back again. When the conversation lagged, Hu urged us, “Ask, ask, ask. Anything you can think of.” He was quite open to conversation. I have never seen such openness in Chinese politicians before: they always try to say less than a journalist hopes to get. So, Hu Yaobang was a special case. Some things we heard from him for the first time. For example, that during the “Cultural Revolution,” three million people were killed and one hundred million were subjected to some kind of repression. Before and even after, Chinese politicians did not provide specific information about the victims of the “Cultural Revolution.” “Three million people were killed, one hundred million were in one way or another, physically or mentally, injured and politically degraded,” was Hu Yaobang’s response to our question. But he asked us not to publish the number of casualties yet because the Central Committee would still have to make an official statement about it.

Hu reminded us that Deng Xiaoping was also sent for “re-education and that he worked as a mechanic in a small factory. Deng, however, had a fenced-in house back then where he lived with his wife and stepmother. They had a bodyguard with them. Deng got all of this because of his self-criticism at a meeting of the political leadership. That’s why he remained in the party. It was a pragmatic procedure that saved his head and allowed him to rehabilitate himself, albeit briefly. Later, in the spring of 1976, he was again removed from all posts.

We asked Hu Yaobang if anything like that happened to him after falling into disgrace. He replied briefly that after working in a stable where he took care of horses and cleaned the stable premises, he was isolated and ended up in a village where he had no work at all. Returning to Beijing in 1972, a few months before Deng Xiaoping’s rehabilitation, he found “refuge” at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 1975, but later had to flee from there too to save his head.

‘Please don't publish it, but you can pass it on to your ambassador”

In our reports about the meeting to our press we did not reproduce everything Hu Yaobang said to us at that time. The General Secretary asked: “This is for your information only. Please don’t publish it, but you can pass it on to your ambassador.”

The most important thing that Hu Yaobang said was the announcement that “Comrade Hua Guofeng will no longer be Chairman of the Central Committee and Chairman of the Military Council of the Central Committee.” “At the Politburo meeting,” he said, “we criticized Hua Guofeng in a friendly manner for his mistakes during the nearly four years after the arrest of the Gang of Four, when he led the Party, the government and the Military Council of the Central Committee. He accepted our criticism and said that he was ready to step down from his posts. Of course, he had his own merits in destroying the Gang of Four, so he would continue to be a member of the Central Committee.”

We asked what mistakes Hua Guofeng had made, and the General Secretary of the CPC Central Committee told us that they were “leftist mistakes” like those made by Mao Zedong during the 'Cultural Revolution.' “There is no human being who is immune to mistakes,” Hu said. “Do you think Marx was sinless? Or Lenin? Our leader Mao Zedong, who made great contributions to the creation of New China and was the main creator of Chinese socialism, made serious political mistakes in the past twenty years and bears the greatest responsibility for the “Cultural Revolution.” This “Cultural Revolution” was the greatest tragedy of the Chinese people. Hua Guofeng has been criticized for his statements that everything Mao said must be implemented, which is actually a leftist approach that we have criticized. Also, we believe that one person should not have so many posts in the party and government, and I think in the future there will not be such a position – Chairman of the Party – as there is now. We are in favor of collective leadership.”

Hu Yaobang asked us not to publish anything about Hua Guofeng and the numbers of “Cultural Revolution” victims. We asked why, and the General Secretary said we should wait for the official decision from the Central Committee, but in the meantime, Hua would continue to fulfill his duties, receive foreign delegations, etc.

In the fall of 1980, after I returned to Belgrade at the end of my business trip, Hua Guofeng was still in charge of China. In the meantime, I learned that the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee had held eight or nine meetings on all these issues and had sent a secret letter to Party cadres informing them of the criticism of Hua Guofeng and his impending resignation. There were even two large meetings with four thousand participants each, who were also told to consider the Politburo’s decision as confidential information that under no circumstances should be discussed before the Central Committee plenum.

Decisions were made much earlier than announced to the public

The plenum took place exactly one year after our meeting with Hu Yaobang in Zhongnanhai. [Translator's note:It took place on June 27-29, 1981.] Hua Guofeng’s resignation was accepted (he remained a member of the Politburo), Hu Yaobang was elected as the new Party Chairman, Zhao Ziyang Prime Minister, and Deng Xiaoping Chairman of the Military Council. A year later, the position of Central Committee Chairman was abolished and Hu remained the Party’s General Secretary.

Everything Hu had told us in the summer of 1980 was confirmed. I was thinking at the time about how and when important political decisions were made in China. Apparently, decisions were made much earlier than they were announced to the public. And Hu had displayed courage by announcing them in advance and, moreover, to foreign journalists!

Hu Yaobang was not a typical party leader. We got the impression that he was sharp-tongued, although he had always adhered to the Party’s decisions or directives. In a conversation with us, he repeated several times that we should “seek truth from facts.” This was actually Mao Zedong's formula, from which Mao himself was the first to depart.

Hu spoke openly about the Party's mistakes and the people who made these mistakes. It was enough for him to recognize the mistakes and continue to work in a new way. He was very active in rehabilitating the CPC leadership. In his talk with us, he mentioned that about one hundred million people who had suffered from the “Cultural Revolution” had returned to economic and political life. Hu said he realized that China needed them now, but added that the cadre structure should be renewed immediately. One of those rehabilitated at his initiative was Xi Zhongxun, father of the current Chinese President Xi Jinping.

A Follow-Up Exchange between Aleksandr Novačić and Dmitry Goncharov and Alexander V. Pantsov

After reading these recollections, Dmitry Goncharov and Alexander V. Pantsov prepared questions for Aleksandr Novačić hoping to receive his answers that would shed additional light on the unique figure of Hu Yaobang and on Communist China. Here’s what came out of it.

– Did Hu talk about the reforms in the countryside?

– Yes, he said that the reform began in the countryside because 80 percent of the Chinese population lived there. He also said that Sichuan Province had the best results. The experience of that province was gradually spreading throughout the country.

– What was his attitude toward Stalin, Bukharin, Trotsky?

– He mainly spoke about Stalin and he spoke negatively, but at the same time Hu said that Stalin’s huge portrait must remain on the Tiananmen Square for some time (along with images of Marx, Engels, and Lenin), because “people would not understand if it were removed overnight.”

– Did you talk about the forthcoming Liu Shaoqi’s rehabilitation?

– He said that all repressed politicians will be rehabilitated gradually. Not only those who fell during the “Cultural Revolution,” but also those who were victims of the intra-party struggles before that. Liu Shaoqi will be rehabilitated in about a month after our meeting with Hu at the Fifth Plenum of the CPC Central Committee. [Translator's note: Liu was rehabilitated on February 24, 1980.]

– Did he talk about Kang Sheng's role in the "Cultural Revolution"?

– We did not talk about that.

– How did he feel about Wei Jingsheng and the “Democracy Wall”?

– We didn’t talk about that.

– Did the meeting give an impression that Hu Yaobang was a kind of a “misfit” among the top leadership of the CPC and the PRC?

– He was an unusual person among the politicians at the top of China. That was the impression he made on us during the conversation. He was open to all the questions we asked without any taboo topics.

– How liberal did Hu seem to you, based on what was said in the conversation?

– There have been similar ideas in the Chinese press from time to time, presented more or less freely. Of course, there have been other opinions also. Hu Yaobang represented the new wind of change in China, briefly but without formalities.

– Journalists who met Hu Yaobang and saw him in the early 80s had an impression that he was a simple, accessible man who did not surround himself with the trappings of pomp and luxury. Do you share this impression?

– Yes, we have that impression too.

– What was his assessment of the Soviet Union and the history of Sino-Soviet relations?

– He said that China’s foreign policy is based on the theory of three worlds. In the first world, there are two leading hegemonic powers, the United States and the USSR, of which the Soviet Union is the most dangerous one. The second group includes developed countries, and the third group includes developing countries including China. We did not get an impression from his speech that we should expect a change for the better in Soviet-Chinese relations. Unlike the change in relations with other Eastern European countries.

– What was his attitude towards the U.S., Japan, other leading powers?

– He did not speak directly about the prospects of relations with the U.S. and Japan, but hinted at improving relations with Western European countries, announcing some visits, for example, a visit of Francois Mitterrand. [Translator's note: Francois Mitterrand visited China from February 9-16, 1981, a few months before he was elected the 21st President of France.]

– Were the following topics discussed in the conversation: Pol Pot’s genocide in Cambodia, China's role in supporting the Pol Pot regime, the causes and consequences of China's military actions against Vietnam in February-March 1979?

– We didn’t talk about these.

– How far ahead of his time was Hu?

– Hu Yaobang was a vivid representative of the new thinking in China after the death of Mao Zedong. But the main actor was still Deng Xiaoping.

– Could China have taken a different path if Hu Yaobang had lived a few more years and become the supreme ruler of China?

– I don’t think China would have gone a different way. This country is huge. The Chinese traditions, the old cadres, and the political relations in the society could not be radically changed. Mao himself tried to change China radically, although in a different direction, during the "Cultural Revolution".

– But, as we know, he failed.

– That’s right.