A blog of the Indo-Pacific Program

Introduction

U.S. relations with Southeast Asian governments have not seen a significant uptick over the past decade. It is in contrast with officials’ acknowledgment of the increasing importance of Southeast Asia to strategic competition against China and in its overall Indo-Pacific strategy. Yet the relationship is seemingly stagnant on surface. There are, however, signs of a unique transition in U.S.-Southeast Asia relations taking place in terms of elite network formation through the relative decline of old security networks and the rise of new social entrepreneur networks, largely via the Young Southeast Asian Leaders Initiative (YSEALI) program.

At best, signs of decline or stagnation in the old relationship between the United States and Southeast Asia can be found in notable cases in the past decades. Thailand is one example. During the first three years after the post-2014 Thai military coup, the United States refused to welcome Thailand's leaders and cabinet members, a formal military ally in Asia, to Washington, all while welcoming another coup leader from Egypt during the same period. In the case of the Philippines, newly elected Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte’s public cursing of the sitting U.S. President in 2016 and his use of the Visiting Forces Agreement as a bargaining chip were beyond precedent from an ally. The messaging and communication between the United States and the newly installed governments in two Southeast Asia allies clearly showed the decline in U.S. relations.

This damage continued into the Biden Administration. Two months into its presidency, the National Security Council (NSC) published an Interim National Security Strategy Guidance to emphasize that the administration is "committed to engaging with the world" to meet its strategic goals. They stressed the need to "renew its enduring advantage," which is to "revitalize America's unmatched network of alliances and partnerships."[1] To publish this “Interim” guidance swiftly after two months in office intended to reassure its international audience. However, it was a blow for Southeast Asia considering that the two treaty allies, the Philippines and Thailand, were not mentioned in the paper amongst the others. Australia, Japan, and the Republic of Korea were referred to, along with NATO, as America's greatest strategic assets. This contrasting omission was further reconfirmed as not a typo by emphasizing it would deepen its relationship with Singapore, Vietnam, and "other Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member states."[2] Again, no specific reference to Philippines and Thailand.

The "loss" of the Philippines and Thailand in the National Security Strategy (NSS) papers is a new phenomenon. Previous NSS documents, back to the one published in 1987, never missed acknowledging the importance of the two Southeast Asian countries as key strategic allies. Even in 2015 immediately after the coup in Thailand, the NSS confirmed its commitment to upholding treaty obligation with Thailand as an ally while encouraging Bangkok "to return quickly to democracy."[3] Hence, the lack of reference to Thailand and the Philippines stood out from a Southeast Asian perspective. The slip signals to Southeast Asian partners, rightly or wrongfully, that Washington undervalues the relationship.[4]

These cases can be alternatively understood as a result of structural and strategic changes incurred by the negative impact of the U.S. withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and Southeast Asia’s increasing trade and investment relations with China. The United States’ lack of attention to the region can also be blamed, as the United States diverted its defense and diplomatic attention elsewhere, namely North Korea and Syria during the Trump Administration and Afghanistan, Taiwan, and Ukraine during the first years of its Biden Administration.[5]

Regardless of its cause, it is difficult to ignore the diplomatic and strategic costs resulting from a lack of communication between the United States and Southeast Asia. In other words, it is a sign of insufficient “gardening” in the late Secretary of State George Shultz's analogy for diplomacy, which he elaborates as, “The way to keep the weeds from overwhelming you is to deal with them constantly and in their early stages,” in other words, “to see people on their own turf, where they feel at home and where you meet people with whom they work.”[6]

In line with Secretary Schultz's analogy, this paper argues that the design of the U.S.-Southeast Asia garden is transforming. The attention paid toward the policy elites who have been part of the NSC community is in relative decline, but the United States is making a significant and innovative gardening effort to foster a new stream of networks between Southeast Asia emerging powerful elites: social entrepreneurs.

The Young Southeast Asian Leaders Initiative (YSEALI) program

Social entrepreneurs in Southeast Asia have been developed primarily through the U.S. government-funded Young Southeast Asian Leaders Initiative (YSEALI) program. The program provides educational and cultural exchanges, regional exchanges, and seed funding programs to strengthen leadership development and networks in Southeast Asia started in 2013. Unlike changing U.S. trade policies, the program has been a robust and consistent U.S. policy towards Southeast Asia in the past decade. It has set up a new platform for U.S. influence in the region in an era of great power politics.

YSEALI is designed to help Southeast Asian youth under 35 years of age. The rationale behind this targeted age group is because of the demographic nature of Southeast Asia. Approximately 65 percent of people in Southeast Asia are under the age of 35. YSEALI is an effort to harness the extraordinary potential of youth in the region to address critical challenges identified by youth in the region, such as Civic Engagement, Economic Empowerment, Social Entrepreneurship, Education, and Environmental issues.[7]

While YSEALI seeks to build the leadership capabilities of youth in the region, the program also aims strengthen ties between the United States and Southeast Asia. This is to set a new field for cooperation and a common platform for political economy centered on social entrepreneurship. The State Department claims the number of program participants has already reached 150,000 people,[8] which is a solid de-facto U.S. constituency in the fast-changing Southeast Asia region.

In understanding the United States and its Southeast Asian strategies during a dynamic era, an initiative to reorganize the human network centered on social entrepreneurs is an ambitious initiative regardless of its budget size. Despite the small-sized budget, due to its growing number of participants and stakeholders, especially among the young generation, the program promises to have a standard-setting power in the United States' relations with the region. For this purpose, the paper highlights the significance of YSEALI and how this could have strategic importance on US policy toward Southeast Asia and beyond.

Surviving Three Presidencies

One of the strong achievements of the program is the fact that it survived three presidencies. This took place during the time when denial of foreign policies of a previous administration was the standard. The program's survival, especially from the Obama administration to the Trump administration, is worth noting when other flagship policies at the heart of Southeast Asian policy, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership, were quickly canceled. Clearly, Washington views the program as an important value-add for U.S. foreign policy in the region. New foreign policies such as the so-called Muslim entry ban sent cautioning message to countries like Indonesia and Malaysia, signaling a drastic change in U.S. stance as if turning back against Southeast Asia. Had the YSEALI program been canceled in those moments, it would not come as a surprise as the program was personally attached to President Obama.

When the program started in 2013, the model was the Young African Leaders Initiative (YALI) started in 2010.[9] As a President of the United States, he had a rare personal background of spending his youth period in the region, specifically in Jakarta. Because of his experience in Jakarta and his mother spending years working in the villages as an anthropologist to help women improve their lives, he recalled “Southeast Asia shaped who I am and how I see the world.”[10] This personal background was a bonus for U.S. foreign policy to Southeast Asia. It made it significantly easier to convince the President of the region's importance and that it would take a long-term commitment.

While the President’s strong support and full attention give full momentum to launching and pursuing such a new program, this could also create a paradox. It is a paradox that the program could be tied too personally to the President, resulting in the program being unable to survive beyond the term of his presidency. The Obama administration called the program "the President's signature program to strengthen leadership development and networking in ASEAN, deepen engagement with young leaders on key regional and global challenges."[11] Ironically, this is where dilemma arises. The more the government announces its importance as “the President’s” signature program, the less likely the program would survive beyond his term considering the divisive political climate in the United States. Therefore, the Obama factor was not only a bonus but was also a liability.

This anticipated liability became a reality when President Trump won the 2016 Presidential Election. Significant policy changes awaited, and naturally, “the President’s Signature program” was well-positioned to cease. Another scenario was that the program could have been transferred outside the government. For instance, housing it under the Obama Foundation, because President Obama personally cared so much and had all the reason to keep his hand on it. As the program was managed at the State Department, the officers had to work not only for the program to thrive but also to manage the program as the President instructed and to ensure the program remained under the government. During the transition period, the officers made a great effort in explaining that the program would better function as a government program and, therefore, convince the successive leadership of its value and importance of the program. The aim was to win the support of Vice President Mike Pence to endorse the program. This was, in a way, an effort to remove the association with the predecessor administration from the YSEALI program.[12]

The decisive moment in whether the YSEALI program would survive as a U.S. government program, not an Obama administration program, came when Vice President Pence toured Southeast Asia in April 2017, three months after his inauguration. The careful work of the State Department paid off when, in April 2017, Vice President Pence met YSEALI members in Jakarta. They tweeted his praise: "The future of Southeast Asia looks bright thanks to great programs like @YSEALI that help prepare future business and civic leaders."

This public endorsement by Vice President Pence secured the continuity of the program and paved the way for firm bipartisan support in the congress. The budget for the YSEALI program increased from $500,000 to $800,000 between 2015 and 2016 respectively,[13]and again to $9.3 million in 2020.[14]

The program also survived another political transition period into the Biden administration. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, upon his visit to Jakarta in December 2021, also referred to YSEALI as a "signature program” to empower a rising generation of leaders in Southeast Asia. Secretary Blinken emphasized that the program has already created a membership community above 150,000 people.[15] Its budget has also grown more than during the Trump administration.

The next question would be to what extent YSEALI deserves such strong effort by the State Department and bipartisan lawmakers. The budget of the YSEALI program could be perceived as minuscule compared to other diplomatic programs, development aid, and assistance, such as in the fields of infrastructure, energy, and military. However, due to its number of members and the program's beneficiaries, I would argue that the political and social influence of the YSEALI program far exceeds the size of the allocated budget. This is a strategically undermined aspect of the YSEALI. The YSEALI program’s survival across multiple administrations was a task as challenging as its launch. Therefore, establishing bipartisan support for the program could be regarded as one of the best articulated and well-executed Southeast Asian policies by the State Department. Below are a few key reasons why the program is so persuasive to policymakers:

Renewing and restructuring the network

Previously, "the signature program" of the U.S. government for Southeast Asia in establishing practical terms of human capital development had two pillars. One was a military officers' training program, and another, higher education for developing economists. The flagship program was known as the IMET program for military officers. It was instrumental, especially during the Cold War up to the 1990s, and cultivated military leaders among partner countries capable bridging the gap between militaries and becoming influential leaders in their countries. One of the notable successes of the overall program is Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, who became the first directly elected President of Indonesia after successfully reforming the Indonesian Military Force during the democratic transition period.

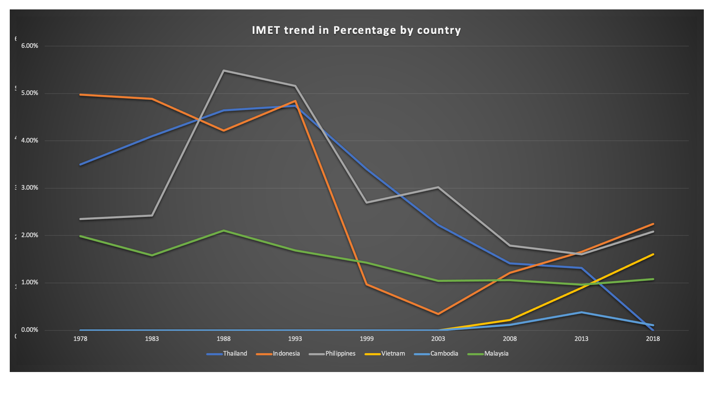

The program budget has grown. However, with the post 9.11 War on Terror understandably shifting its resources to the Middle East, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, the IMET program initiated network in Southeast Asia has grown thin, as shown in Table 1 where treaty allies like Thailand and the Philippines are losing quotas. Comparing the numbers between 2009 and 2019, we see a sharp drop in the number of Southeast Asian officers receiving IMET training program from 428 to 85 personnel (See Table 2). As experts have been critical, the U.S. government has not utilized the IMET program to the extent likely needed to maintain close relations with strategic partners, advance democratic values, and nurture military officers who may become influential policymakers. It is also clear that Southeast Asia is under-resourced, despite a broad agreement that the region is an increasingly important strategic front vis-à-vis China in its great power competition.[16]

Another U.S. fostered network is between economic leaders. It is the network that the United States cultivated through its higher education institutions by training economists and technocrats who speak the same language as the U.S. economists and policymakers. One of the flagship programs of this network is the Harvard Institute for International Development (HIID), which started in the 1950s to provide technical assistance to the development planning agencies in participating countries supported by the Ford Foundation and UNDP budgets.[17] Notable leaders are Indonesia’s Widjojo Nitisastro and Ali Wardhana, the chief economic technocrats during military rule in Suharto’s Indonesia, the so-called Berkeley Mafias.

The network of these economists grew beyond the cold war period. The period between the 1990s and 2000s saw a great increase in the number of students who had arrived in the United States to study. However, the number of Southeast Asia students coming to the United States has passed its peak, especially in major regional economies, such as Indonesia and Thailand. One reason is the increasing proportion of students who favored studying in Australia and the UK.[18] This means that simply relying on this diminishing network of Southeast Asian students is not enough to strengthen the U.S.-Southeast Asia relationship.

Therefore, aside from building a network of military officers and economists, it became clear that, if the United States aims to strengthen its network with Southeast Asia, the United States would need to tap into a new network channel. In this context, YSEALI, which is not a university degree program but rather a short visit training program both in the United States and in the region, has opened a channel to connect with grassroots social entrepreneurs. This was not just a substitution for decreasing numbers in the IMET programs and university students from Southeast Asia. However, it is more a creation of a new network hitherto overlooked.

As we are now witnessing the rise of new social entrepreneurship and intelligent humanitarianism in Southeast Asia, where governance, rights, and humanitarian practices are increasingly dealt with technologically, it is strategically critical that this social entrepreneurship is expressed via shared ideas and shared languages between Southeast Asia and the United States to connect this emerging social entrepreneurship class.[19] The traditional concept of good governance and development places bureaucrats and military officers as the central agents. That is why human capital development was centered on military officers and economists for a long time.

Contrastingly, with the YSEALI program, placing social entrepreneurs in the center makes the network unique. In such a way, the State Department would be able to connect with this critical emerging class through short-term trainings and the offering of seed money to enhance their practices. Investigating the YSEALI Seeds projects (multi-national social/social entrepreneurship projects) and grant recipients,[20] the awardees are not selected in line with the traditional concept of “good governance” but more of a business model of the triple bottom line, the profit, people, and planet. In other words, financial, social, and environmental sustainability.

YSEALI could be considered a U.S.-led international movement of social entrepreneurship, capturing the rising class in the region rearranging the concept of development and governance. Despite its shortcomings, this approach, strategically speaking, is a resounding victory for U.S. diplomacy in establishing a platform and network centered on this new class, while other countries have not tapped into it. The United States, with the help of YSEALI, has established its position as a Mecca for social entrepreneurs. Therefore, the program and the State Department should deserve higher political recognition for this achievement.

Anchoring the United States in Southeast Asia

The YSEALI program offers more than creating a new network between Southeast Asia and United States. The program also neutralizes the classic critique against the United States that the "United States is not a neighbor," meaning that Washington will come and go, unlike China, Japan, and South Korea. First, on the consistencies, the IMET program has indeed come and gone, as we see a sharp decline in military officer exchanges in post-coup Thailand or Indonesia after the Timor Leste human rights violations. As U.S. law prohibits IMET funding for a country where a "duly elected head of government is deposed by military coup," these program do “come and go” while, on the other hand, YSEALI does not. For example, in the post-February 2021 coup in Myanmar, the YSEALI Seeds for the Future program awarded three recipients from Myanmar funding. This is the same for post-coup Thailand, Cambodia after its opposition purge, and other political human rights violations in Southeast Asia. As the funding is awarded to a non-governmental actor, YSEALI is in an excellent position to bypass the values versus strategy dilemma in U.S. foreign assistance, while remaining consistent in the region.

Another positive effect of YSEALI is in bringing American faces to the region. One of the significant differences between the United States and China, Japan, and South Korea is that there are far fewer U.S. residents in the region. With a large population of residents in Southeast Asia, this would naturally create both a comfortable constituency in the region and to create a ballast when government to government relations turns sour.[21] Top U.S. officials have recently defined the U.S. position as "the biggest investor" in the region, which could win the business community's attention, but not necessarily the Southeast Asian public. That is why the mass membership of YSEALI matters, as this could be seen as the biggest friend-making platform. One does not have to be a dignitary nor a successful recipient of the seed money to be a member.

This low bar for membership combined with its "town meetings" with high-level officials setting an opportunity for Southeast Asian youth to directly talk to U.S. Presidents, Vice Presidents, and Secretaries of State without visiting the United States is a unique method in bringing American faces into the region efficiently. YSEALI is an upgraded version of public diplomacy combining a low cost and high-level meetings, which has not been done before in the region.

Table 1: IMET allocation by country

Source: U.S. Department of State, Foreign Military Training and DoD Engagement Activities of Interest

Table 2: IMET students/cadets comparison between 2009/2019

Country

IMET students/cadets FY2009

IMET students/cadets FY2019

Brunei

0

N/A

Myanmar

N/A

0

Cambodia

1

0

Indonesia

63

21

Laos

1

12

Malaysia

64

12

Philippines

121

26

Singapore

0

0

Thailand

128

0

Timor Leste

41

1

Vietnam

9

13

Total

428

85

Source: U.S. Department of State, Foreign Military Training and DoD Engagement Activities of Interest

The United States stands for social mobility

The third point of the success of YSEALI lies in its resiliency against the rising populist political climate in Southeast Asia. Democratic regression, democratic setback, and illiberal populism have been the common term to describe Southeast Asian politics, especially since the 2014 Thai coup. Several key rationales behind this rise of populism could be attributed to distrusting the government's liberal economic policy, which expands inequality and limits social mobility. Hence, this would set up a perfect political context to demonize the elites and their foreign partners, who unjustifiably reap the benefits of liberal policy and its global network. This puts any foreign initiative to strengthen human connections as a target of political attack.

While the transnational nature of the capital market highlights the business elite connection between the U.S. business and the Southeast Asian top business owners, they both risked being a political target derived from the worsening inequality. Should social class conflicts worsen in Southeast Asia, the United States would automatically become a liability, and being a friend of an American could be portrayed as social risk in the respective countries.

While all the above agenda addresses inequality and social mobility, the YSEALI program also neutralizes the risk of the United States being targeted in an anti-elitist populism, which could be seen not only in Southeast Asia but also at home in the United States too.

While all the above agenda addresses inequality and social mobility, the YSEALI program also neutralizes the risk of the United States being targeted in an anti-elitist populism, which could be seen not only in Southeast Asia but also at home in the United States too. This means that the YSEALI program significantly contributes to U.S. corporate activity. Thus, the programs' choice of themes on Civic Engagement, Economic Empowerment and Social Entrepreneurship, Education and Environment issues was thoughtful and fitting.

A further important aspect of the program’s choice is that this also brings optimism of social mobility within the youth of respective countries. According to the Global Social Mobility report produced by the World Economic Forum, among the 82 countries covered, Laos was 72nd, Indonesia 67th, Philippines 61st, Thailand 55th and Vietnam 50th.[22] Low social mobility can result in socio-economic precarity, loss of identity and dignity, weakening social fabric, eroding trust in institutions, and disenchantment with political processes.[23] If we see the ultimate purpose of U.S. Southeast Asia policy as an open-door policy, or to prevent another great power from isolating the United States from the western pacific,[24] it is not only China that could close that door, but also Islamic radicalism as well. What we know from other secular states such as Egypt is that decline in social mobility combined with inequality can produce a religious revival led by the educated middle class.[25] And especially following COVID, where unequal footing in social can further hinder any improvements in social mobility, this could either bring in a religious uprising or strongman rule to address their unfulfilled aspirations. In both cases, it could lead to both an illiberal economy and xenophobic nationalism.

What is needed are economic growth, an improvement in the quality of life, and the fulfillment of youth aspirations. However, when economic growth cannot be reliably expected, this is where the YSEALI program can make a significant change in improving the quality of life and restore optimism to the middle-lower to lower classes. With YSEALI, the United States is in the best position to stabilize Southeast Asia’s socio-economic conditions, which would give it a major advantage in cultivating trust and security for ensuring a U.S. presence in the region.

In Conclusion

“How are the inequalities inherent in modern economic organization defused or overcome as a source of explosive social conflict,” askes historian Charles S. Maier in his book In Search of Stability.[26] He continues: "This inquiry includes several interlocking questions: What mixture of constraint and ideological legitimation, what forms of representation, what promises of material reward support political and social stability? Under What circumstances is stability threatened; under what circumstances is it recovered? How does the alignment of power among nation-states influence the tensions and rivalries within national societies?”

The United States has a new (tentative) answer for these questions, recurrent and relevant to the current environment, social entrepreneurship promoted in the form of YSEALI program. As much as the “New Deal” economic concept served as the backbone for “exporting” the ideological basis of development policy during the cold war period and has set the foundation of “the politics of productivity,” social entrepreneurship can be considered the new ideological basis for “exporting” a governance model in the digital era.

As much as the “New Deal” development model also established a transnational U.S.-Asia elite network of economists and technocrats during the Cold War period, I would argue that the YSEALI program is also formulating an emerging network of social entrepreneurs who can serve as the foundation of an American international political economy in the coming era of great power competition.

As much as the “New Deal” development model also established a transnational U.S.-Asia elite network of economists and technocrats during the Cold War period, I would argue that the YSEALI program is also formulating an emerging network of social entrepreneurs who can serve as the foundation of an American international political economy in the coming era of great power competition.

It is yet to be seen whether this would lead to another form of enhancing both the welfare of all nations and American predominance. Bretton Woods was the case 70 years ago in supporting currency stability and international trade through foreign aid.

Currently the cost of establishing an international system of social entrepreneurship is comparatively trivial. But while YSEALI finding its path to broaden its size and scope, this program can form the backbone of U.S. foreign policy to Southeast Asia while developing an Anglo-Asian elite in Southeast Asia, a group of elites who approaches and identify social issues through similar methods, procedures, and in the same language for the same overall goal that it does in the United States. Indeed, the Secretary of State has continued to hold meetings with YSEALI members in every Southeast Asian trip itinerary, thus demonstrating its importance. It is a new version of diplomatic “gardening,” "to see people on their own turf, where they feel at home and where you meet people with whom they work."[27] This quote originally referred to government officials, but now can be said about social entrepreneurs.

With the advancement of technology, social entrepreneurship will increasingly substitute the role of government in offering public services with an entrepreneurial pursuit and can claim the role of a de facto para-bureaucrat. With the YSEALI program in full stream, this trend could be in the United States’ strategic favor as its alumni could be at the heart of innovative governance in the region.

One caveat remains: the issue of accountability. The democracy issue resurfaces again amidst COVID, where philanthropic giants face questions of accountability in its medical care service offers.[28] While U.S. support is on the side of young entrepreneurs to incubate, we have yet to have any mechanism to innovate the government, which can help bring accountability while keeping the incubation active.

This may be beyond the role of the YSEALI program and its alumni and requires more delicate research on how different countries shape the concept of “social entrepreneurship" differently in times when the nature of governance is changing rapidly. But what is clear now is that the current global challenge on the need of new form of governance underscores the U.S. benefit in having YSEALI alumni and to be in the front seat in articulating a new form of governance in a way conducive to the practice and ideas in the United States. YSEALI is developing social entrepreneurs in Southeast Asia, and therefore is both shaping a new standard of governance in the region and, by doing so, rebuilding American socio-political power in Southeast Asia.

The views expressed are the author's alone, and do not represent the views of the U.S. Government or the Wilson Center. Copyright 2020, Asia Program. All rights reserved.

[1] The United States. President (2021- : Biden). Interim National Security Strategic Guidance, (Washington, DC: The White House, 2021).

[2] Ibid. The omission of Thailand and the Philippines among the "allies" in Asia was later rectified in the Indo Pacific Strategy report issued in February 2022. (https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/U.S.-Indo-Pacific-Strategy.pdf)

[3] The United States. President (2013- : Obama). National Security Strategic Guidance (Washington, DC: The White House, 2015).

[4] Various critics have laid out this point and argue that this is a trivial matter as the 2021 guidance is an "Interim" one, not a complete strategy paper. However, when a strategy tells that their advantage is having allies and then misses to name an ally country proves the drafting team's lack of attention, interest, or knowledge. This hinders the report's overall message, emphasizing the importance of reinvigorating its relationship with allies and partners.

[5] This is not to disregard entirely the U.S. commitment to the region based on its growing U.S. investment toward the region and increasing numbers and scales of joint military exercises in the region. According to the ASEAN Secretariat, ASEAN FDI database, in 2015, 2017, 2019, and 2020, the U.S. topped the list, outnumbering China and Hong Kong combined. In 2016 and 2018, the largest investor was Japan.

[6] George P. Shultz, Turmoil and Triumph, (Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, 1993), p. 128.

[7] Details of the program could be confirmed on the US mission to the ASEAN website. (https://asean.usmission.gov/yseali/yseali-about/)

[8] Antony J. Blinken Secretary of State, ‘A Free and Open Indo-Pacific’, Speech Delivered at Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia December 14, 2021. (https://id.usembassy.gov/a-free-and-open-indo-pacific/)

[9] The young leader's program also was followed by the Young Leaders of the Americas Initiative (YLAI) in 2015 and The Young Transatlantic Innovation Leaders Initiative (YTILI).

[10] The White House, Remarks by the President in Town Hall with YSEALI Initiative Fellows, June 02, 2015. (https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/06/02/remarks-president-town-hall-yseali-initiative-fellows)

[11] FACT SHEET: The President’s Young Southeast Asian Leaders Initiative, The White House

Office of the Press Secretary, April 27, 2014.(https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/04/27/fact-sheet-president-s-young-southeast-asian-leaders-initiative-0)

[12] Interview, Anonymous.

[13] A minimum calculation of the whole budget could identify as the budget used for YSEALI. The Secretary of State, Congressional Budget Justification Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Fiscal Year 2016, The Secretary of State.

[14] The Secretary of State, Appendix 1: Department of State Diplomatic Engagement FY2022, the Secretary of State.

[15] Antony J. Blinken Secretary of State, ‘A Free and Open Indo-Pacific’, Speech Delivered at Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia December 14, 2021. (https://id.usembassy.gov/a-free-and-open-indo-pacific/)

[16] See for example, Kurlantzick, Joshua, Reforming the U.S. International Military Education and Training Program, Council on Foreign Relations, Washington DC, USA. June 08, 2016. (https://www.cfr.org/report/reforming-us-international-military-education-and-training-program)

[17] Joseph J. Stern, ‘Indonesia–Harvard University: Lessons From A Long-Term Technical Assistance Project,’ Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 36:3, 113-125, 2000.

[18] Wu, Irene S. "9 Applying the Soft Power Rubric: How Study Abroad Data Reveal International Cultural Relations". Cultural Values in Political Economy, edited by J.P. Singh, (Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2020), pp. 173-200.

[19] On the rise of social entrepreneurship and Smart humanitarianism, see Dale, J., & Kyle, D. Smart humanitarianism: Re-imagining human rights in the age of enterprise. Critical Sociology 42(6), 783–797. 2016. Dale, J., & Kyle, D. Smart transitions? Foreign investment, disruptive technology, and democratic reform in Myanmar. Social Research, 82(2), 291-326, 2015.

[20] The awardee could be seen on the Cultural Vistas' YSEALI Seeds page: https://culturalvistas.org/our-programs/yseali-seeds/

[21] One example is the role of the Japanese business community in Thailand in balancing the conflicting social and political interests. See Aizawa, Nobuhiro, 'The Japanese Business Community as a Diplomatic Asset and the 2014 Thai Coup d'État,’ in John D Ciorciari, Kiyoteru Tsutsui (eds.), The Courteous Power: Japan and Southeast Asia in the Indo-pacific Era, (University of Michigan Press, 2021).

[22] World Economic Forum, The Global Social Mobility Report 2020 Equality, Opportunity and a New Economic Imperative, January 2020. (https://www3.weforum.org/docs/Global_Social_Mobility_Report.pdf)

[23] Ibid.

[24] Michael J. Green, By More Than Providence: Grand Strategy and American Power in the Asia Pacific Since 1783, Columbia University Press, 2019.

[25] The principal idea behind this is that religion helps individuals cope with unfulfilled aspirations by adjusting their expectations-based reference points. By raising aspirations, economic development may make societies more prone to religious revivals. Binzel, C. and Carvalho, J.-P. (2017), Education, Social Mobility and Religious Movements: The Islamic Revival in Egypt. Econ J, 127: 2553-2580.

[26] Charles S. Maier, In Search of Stability, (Cambridge University Press 1987).

[27] Despite tight restrictions on in-person meetings, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken, during his visit to Southeast Asia in December 2021, did not miss the chance to do a town hall meeting in Malaysia. He also did not miss speaking at the 2021 YSEALI Summit held in October 2021. Quotes from George P. Shultz, Turmoil and Triumph, (Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, 1993), p128.

[28] See for example, during the Covid crisis, few major philanthropic organizations stood out, as the top 11 foundations accounted for 77 percent of the funds philanthropic institutions pledged for U.S. coronavirus relief in the first nine months of the pandemic. (https://theconversation.com/only-a-handful-of-us-foundations-quickly-pitched-in-as-the-covid-19-pandemic-got-underway-early-data-indicates-151752) While we praise their commitment on the one hand, on the other hand, the issue is that it is difficult to identify what and where, which could lead to a source of inequality on de facto public services.

Author

Associate Professor, Kyushu University (Fukuoka, Japan)

Indo-Pacific Program

The Indo-Pacific Program promotes policy debate and intellectual discussions on US interests in the Asia-Pacific as well as political, economic, security, and social issues relating to the world’s most populous and economically dynamic region. Read more