A blog of the Latin America Program

Q: On January 22, 2021, Argentina and Mexico became the final signatories to ratify the Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environment Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean, known as the “Escazú Agreement,” at the United Nations. The agreement, the only treaty to emerge from the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20) in 2012, will enter into effect on April 22, 2021. Strikingly, Colombia, Brazil, Chile and Costa Rica – even though those latter two led the negotiations from the start – have not ratified it. At the regional level, what are the main environmental problems in Latin America that the agreement is designed to address? What legal obstacles stand in the way of pursuing common objectives for sustainable development?

Muñoz Wilson: We’ve ignored the fact that nature has a limit, which has resulted in three simultaneous global crises: the accelerated loss of biodiversity, climate change and COVID-19.

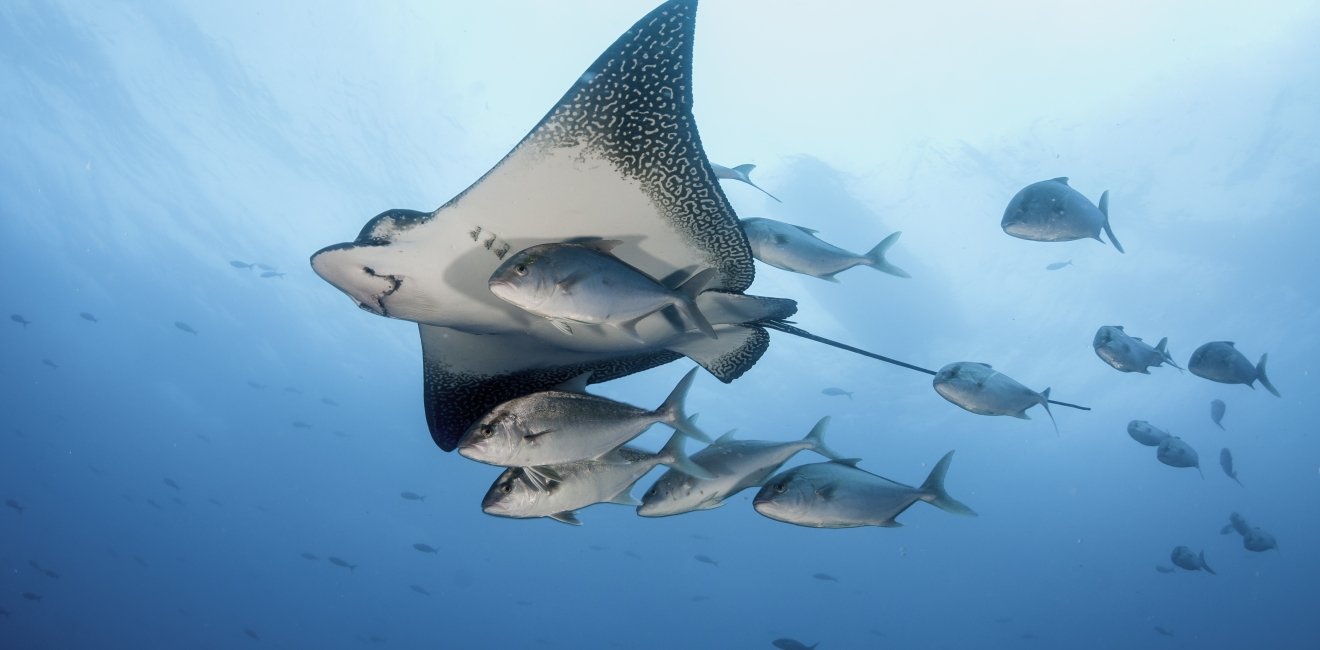

In the ocean, we have overexploited more than 90 percent of big fish, such as sharks and tuna. Two-thirds of fisheries are overfished or even collapsed. Bottom trawling not only destroys the habitat of thousands of species, but releases the carbon dioxide captured in the seabed. In most of our countries, the energy matrix rests to a large extent on coal-fired power plants that severely contaminate the air, sea and land. Deforestation in 2019 destroyed 7.7 million acres of old-growth tropical forest, the equivalent of four soccer fields per minute. The habitats of wild species have been invaded by human activity through the growth of cities, agriculture and ranching. The glaciers are melting from increased temperatures and mining.

Underlying all of these problems is a lack of control over political and corporate decisions. It’s evident that the regulatory and enforcement bodies for the large economic sectors have not been capable of supervising companies, or, at times, have been coopted by them. People and organized groups should possess greater rights and legal mechanisms with which to gain meaningful access to public information, political participation and justice, which are the rights contained in the Escazú Agreement, which Chile and other countries have not signed yet. Under the agreement, our societies would have more tools to control corruption, the decisions of our governments and the behavior of companies.

Q: One of the pillars of the Escazú Agreement is access to public participation in environmental decision making. In this regard, and in line with the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development that establishes that “environmental issues are best handled with the participation of all concerned citizens,” what mechanisms does society possess to guarantee this important right is protected?

Muñoz Wilson: Many countries in Latin America during the past decade have passed access to public information laws and created institutions to promote transparency. We need to elevate that right to the same constitutional level as a human right.

We face a long road ahead to overcome the practical obstacles that people encounter when they attempt to access public information. There are many examples. Sometimes people from rural or remote areas have to go to the capital city to submit and defend their public records requests. Public transparency websites exist, but not everyone has access to the internet. There are language barriers for some indigenous peoples. Many institutions continue to exercise poor practices, such as demanding that access requests be justified even though individuals should not need to state any reason to exercise that right. I’ve also seen a lot of resistance from polluting companies to accept the fact they need to share information that could damage their reputation, which can delay the publication of information for years. Ultimately, governments should become more proactive to guarantee in practice the human right to access public information.

Q: In January, Francisco Vera Manzanares, an 11-year-old Colombian environmentalist, received a death threat on Twitter. Unfortunately, over the last several years, Honduras, Colombia and other Latin American countries have topped the list of places in which environmental leaders are assassinated. According to “Defending Tomorrow,” the annual report from Global Witness, more than two-thirds of the 212 murders of activists in 2019 occurred in Latin America. It is likely that the same trend will repeat itself in the 2020 report. What policies could help enforce the Escazú Agreement’s requirement of effective protection of the human rights of environmental defenders in these countries?

Muñoz Wilson: One of the most novel contributions of the Escazú Agreement is its special attention to protecting environmental human rights defenders. Environmental conflicts in our region are usually associated with a power struggle between big business and poor or vulnerable communities. We’ve seen how companies use different strategies to carry out their projects, from benign and respectful approaches to local communities to acts of corruption, division of communities through bribes and threats and assassinations of leaders in affected communities. The Escazú Agreement requires governments to recognize this brutal reality and take preventative measures to protect defenders when they’re under threat. In accordance with this agreement, it is the obligation of governments to guarantee a safe and conducive environment in which one can act free of threat, restrictions and insecurity. Specifically, governments must adopt adequate and effective measures to recognize, protect and promote the rights of environmental human rights defenders – including their right to life, personal integrity, freedom of thought and expression, to organize and peacefully assemble and freely move – and take appropriate, effective and opportune measures to prevent, investigate and penalize attacks, threats or intimidation.

The defense of human rights is an endless task, and violations will not end with the launch of this agreement. But without a doubt it will provide valuable tools to demand countries adopt effective protective measures.

Q: In a July 2020 report that analyzes the impact of COVID-19 in Latin America, United Nations Secretary General António Guterres highlights the Escazú Agreement as “a valuable tool to seek people-centered solutions grounded in nature.” Now that the Escazú Agreement is soon to enter into effect, what do you think will be its principal contribution to other regions, especially those where conflict and human rights violations are increasingly frequent? What are the principal lessons regarding multilateralism that we might learn from the negotiation of the first regional environmental treaty?

Muñoz Wilson: The Escazú Agreement represents a series of values and principles that are very relevant in our world today. It is an instrument to empower the communities that suffer the harmful effects of environmental destruction. By leveling the playing field with companies and governments, affected people have greater potential to successfully defend their territory. By granting greater social control over government and business, we will surely have a more protected environment. It also deepens the protection of human rights in a post-dictatorship era in which violation of these rights not only comes from state power, but also from corruption and the failure to protect economic, social, cultural and environmental rights. Finally, it is an agreement that puts an emphasis on political reality, on the difficulties experienced by people who defend the environment and on the serious danger that environmental human rights defenders face.

LEER EN ESPAÑOL

-

El Limite de la Naturaleza: Entrevista con Alex Muñoz Wilson sobre el Acuerdo de Escazú

Authors

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Argentina Project

The Argentina Project is the premier institution for policy-relevant research on politics and economics in Argentina. Read more

Explore More in Weekly Asado

Browse Weekly Asado

¿Qué Vemos Hoy?

Uphill Battle for Argentina’s Feminists

ColombIA