A blog of the Polar Institute

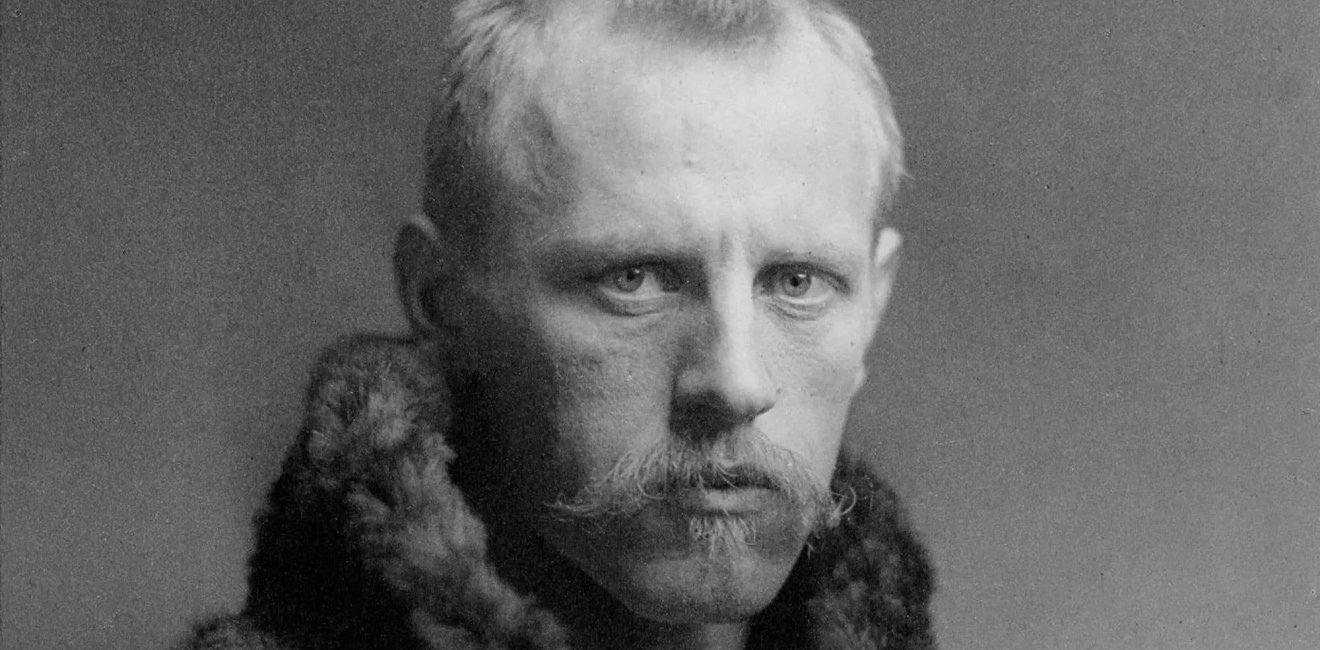

How wondrous to discover a forgotten hero. Before I went to the North Pole this summer, I read the memoir of the greatest Arctic explorer of an earlier era. “Farthest North” chronicles the expedition of Fridtjof Nansen, a Norwegian scientist who had already mastered neurology, zoology, and oceanography before he set off for the North Pole, at the age of thirty, in mid-1893. Most of the planet—except for its icy northern and southern extremes—had already been explored. “More was known about the surface of Mars than about the unexplored regions of the globe,” Roland Huntford wrote in the introduction to the reissue of Nansen’s best-selling book in 1999. “The Arctic was hidden as securely as the dark side of the Moon.”

Nansen was a philosopher too. As he opined in one of his final speeches decades later, "We all have a Land of Beyond to seek in our life—what more can we ask? Our part is to find the trail that leads to it. A long trail, a hard trail, maybe, but the call comes to us, and we have to go,” he said at St. Andrews University in Scotland. “Rooted deep in the nature of every one of us is the spirit of adventure, the call of the wild—vibrating under all our actions, making life deeper and higher and nobler.”

My trip to the North Pole traced part of Nansen’s journey to his Land of Beyond. We both departed on a midsummer’s day at about 78 degrees longitude bound for 90 degrees longitude and latitude —true North. He was on the Fram, a ship uniquely designed for Arctic exploration. (Fram is Norwegian for “Forward.”) I was on Le Commandant Charcot, the world’s largest non-nuclear icebreaker, built for the same purpose. (It was named for the French polar scientist Jean-Baptiste Charcot.) Nansen’s voyage was meant to take three to five years. Mine was meant to be three weeks—there and back. We both witnessed the awesomeness of Earth.

Marveling at the “titanic forces” in the restless ice, Nansen described the echo of towering ridges crashing together, which graduated from gentle moans, then grumbles “till it is like all the pipes of an organ.” The Fram trembled and shook as it rose “by fits and starts.” It wasn’t frightening for him. Nor me, as our ship rocked through the ice too. Experiencing the rumblings of nature can provide a “pleasant, comfortable feeling” when on a strong ship, Nansen noted. The trick is always getting used to the footing. (After I got off the ship, I had to get my land legs again.)

Nansen’s voyage deviated from all earlier explorations. He wanted the Fram to freeze in the ice and then drift with it to the pole. The engine was the ice. My ship—more than a hundred and sixty years later—navigated for days around the ice before heading straight into it. “The direct route is not the fastest route,” the expedition leader told us. Nansen calculated much of the same thing.

Still, like many who embark on risky adventures, including me, Nansen worried. After a year of drifting, the Fram had progressed only three degrees—to 82 degrees north. “Build up the most ingenious theories and you may be sure of one thing—that fact will defy them all,” he wrote. “Was I so very sure? Yes, at times, but that was self-deception, intoxication. A secret doubt lurked behind all the reasoning.” The expedition could take eight years at its sluggish pace, he worried. “I have no courage to think of the future,” he wrote. “Has good-luck abandoned us?” I’ve felt that way, on a smaller scale, amid the human and natural conflicts I’ve covered.

The Fram made history when it came closer to the North Pole than any previous expedition—just beyond 84 degrees—in March 1895. Ice proved an incessant challenge, however. Nansen, who had learned to ski at the age of two, slowly realized that he was not going to make it to the pole. He boldly decided to leave the ship--with only one crew member and 28 dogs—and navigate by foot and sleds into the unknown the rest of the way, leaving the Fram to keep drifting until it reached Norway. On their first nights off the ship, the temperature hit forty-five degrees below zero Fahrenheit. The men shared a sleeping bag in their frozen clothes to generate warmth. In just over three weeks, they trod the windswept tundra to set another human record above 86 degrees north—less than four degrees from the pole.

But as their provisions ran out and their weary dogs began to die, Nansen recognized that they would not make it to the pole. He made a second tough decision to turn toward home. Then, they got stuck. In June 1895, two years after leaving Norway, Nansen described “two grim, black, soot-stained barbarians” surrounded by treacherous ice “and nothing else.” Plus, they were lost. “Where we are is becoming more and more incomprehensible,” he wrote in his journal. My ship, by contrast, had screens in passenger and common rooms that tracked every inch we navigated. It was the first thing I checked every morning when I woke up, as I used to do turning on the news at home. We could do a whole degree in a day.

By August 1895, Nansen and Johansen knew no progress was possible in the looming fall and winter. With no tools, they assembled a tiny squalid hut of stone, moss and skins, with walrus hide for the roof, to wait out the frigid seasons. They stayed there, but off from the world and supplies for nine months.

“Farthest North” is about so much more than polar exploration. It captures the endurance of the human soul. Nansen lamented the vicissitudes of life. “We never could go on with it were it not for the fact that we must.” The two men spent the dark polar days of winter sleeping or listening to a writhing glacier nearby break off icebergs. “There is a noise like the discharge of guns, and the sky and the earth tremble so that I can feel the ground that I am lying on quake,” Nansen wrote. “One is almost afraid that it will some day [sic] come rolling over upon one.” I heard those rumblings too. On one of my zodiac outings in the Arctic Ocean, I saw an aqua iceberg the size of a city block of high-rises that had broken off from its glacier two days earlier, after centuries as one. Other breakaway icebergs occasionally thundered in the distance.

Nansen and his colleague, Hjalmar Johansen, lived in the same clothes all winter. They lacked almost everything. “What would we have not given even for a single box of dog-biscuits—for ourselves?” the Norwegian noted. He longed for a book—the ultimate irony for me. My ship had a book club. We read Nansen’s memoir as we tracked his haunting journey and discussed it over late afternoon glasses of wine. My 21st century ship was also prepared for disaster. It had tents for passengers and crew—16 allocated to each—in case it sank or was stranded. We all had bulky insulated immersion suits stored under our beds. They were bright orange to make us easier to be detected in the desert of ice. Our weather was cold and windy on deck or during outings atop ice floes—at one point hitting 28 knots. But we could retreat to beds, showers, laundry, and thermostats in our rooms. We marveled at the polar bears, seals, and walruses, with no need to shoot them for meat, skin, housing, or blubber.

In April 1896, after a desolate winter and three years since leaving Norway, Nansen and Johansen set off again for home. They still faced repeated mishaps, including their kayaks going adrift with the last supplies. Nansen had to swim frigid waters to retrieve them. I was constantly struck by the advances in technology today as I read Nansen’s memoir. He was born only 87 years before I was, but my ship offered the polar plunge as a perk at the North Pole, complete with attending medical staff and hot toddies afterwards. (Having read Nansen’s account, I didn’t bother.)

Nansen’s salvation was an accidental encounter, two months later, that rivaled Stanley discovering the stranded Dr. Livingstone in east Africa a quarter. Hearing a voice in the distance, Nansen ran over an icy hummock and “hallooed with all the strength of my lungs” in hopes someone would hear him. Someone had.

“Aren’t you Nansen?” inquired Frederick Jackson, a British explorer also navigating the Arctic, when they reached each other face-to-face.

“Yes, I am,” the Norwegian replied. In his journal, Nansen chronicled how he was stinky, his hair and beard unkempt, with both skin and clothes blackened from the amassed dirt and blubber oil. He expressed envy at the sweet soap scent emanating from the Brit.

“By Jove! I am glad to see you,” Jackson retorted. No one had heard about the fate of Nansen or the Fram for three years.

Nansen reached Norway weeks later to global acclaim for the Fram expedition’s pioneering discoveries about the Arctic. (The Fram, by spectacular coincidence, reached Norway a week later.) Jules Verne, the acclaimed author of Journey to the Centre of the Earth, wrote Nansen, “I present my homage to…the hero of the North Pole.” The international media dubbed Nansen a modern Viking. He became the model and mentor for the great explorers who followed him—Shackleton, Amundsen, and Scott.

It was another eight decades before a ship actually sailed all the way to the North Pole. The Soviet Union’s Arktika was first in 1977. The second didn’t arrive for another decade. Getting there is still an ambitious accomplishment. As my ship approached the North Pole, expedition leaders and passengers alike were out on the windy deck with our GPS devices tracking every second as we neared the landmark. We all knew how much it meant. When we arrived, the ship blared “Top of the World” across the deck loudspeakers. Many of us danced, conga-style, around 90 degrees north as we toasted being able to literally travel around the world in about ten seconds.

Nansen did so much more with his feat and fame. He used the global recognition garnered by his discoveries and daring to help sever Norway from Sweden. He was named its first ambassador to Britain. Increasingly acclaimed as a diplomat, Nansen was chosen to be the first High Commissioner for Refugees at the League of Nations. That’s where he made the greatest contribution of his storied life by dealing with the flood of humanity produced by the First World War, the Soviet revolution, the Armenian genocide, and a host of other international crises. He originated the idea of international travel papers for the stateless and refugees—eventually recognized by more than fifty countries—that became known as “Nansen passports.” His work saved the lives of an estimated 450,000 people. Among them were the parents of one of my closest friends, who went on to be a US ambassador to Ukraine. For his humanitarian work, Nansen was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922.

In correspondence between Sigmund Freud and Albert Einstein in 1932, Freud described Nansen as a “lover of his fellow men” who “took on himself the task of succoring homeless and starving victims of the World War.” Nansen used the prize money for international relief efforts. His life’s work is memorialized today at two museums in Oslo—the Fram Museum, which is the ship’s final resting place, and at the Nobel Museum for its Peace Prize laureates.

At the end of his memoir, after returning home, Nansen reflected, “The ice and the long moonlit nights, with all their yearning, seemed like a far-off dream from another world—a dream that had come and passed away. But what would life be worth without its dreams?” His was the North Pole. So was mine. And, luckily, I made it, thanks partly to all he did to make it possible for the rest of us.

Author

Polar Institute

Since its inception in 2017, the Polar Institute has become a premier forum for discussion and policy analysis of Arctic and Antarctic issues, and is known in Washington, DC and elsewhere as the Arctic Public Square. The Institute holistically studies the central policy issues facing these regions—with an emphasis on Arctic governance, climate change, economic development, scientific research, security, and Indigenous communities—and communicates trusted analysis to policymakers and other stakeholders. Read more

Explore More in Polar Points

Browse Polar Points

Ever Forward: The Unique Relationship Between the Arctic and Space

Sea Ice in 2024 – The New Abnormal

Norway’s Supposed Arctic Seafloor Treasures: What Does the Data Show?