As if to distract the people from economic hardship, corruption, and misrule, the government is again focusing on its restless younger generation and on women who do not observe the hijab.

The Iranian government continues to bask in its (unsuccessful) April 13 missile and drone attack on Israel. Meanwhile, it downplays the Israeli attack on one of its military bases in Isfahan that succeeded in causing some damage. War between the two countries was averted, but each country sent a clear message to the other.

Iran’s message to Israel, in so many words, was: ‘we can reach your country with our drones and missiles, and you need the help of other countries to stop us.’ Israel’s message to Iran was: ‘your skies are open to us. We were able to make it to Isfahan, drop our bombs, and return home unscathed.’ Iran is implicitly sending yet another message to Israel: ‘we will continue to support Hamas, and rely on our surrogate militias in Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq, as well as the Houthis in Yemen, to make life difficult for you and show the world that you are not invincible.’

View from inside Iran

In this war of drones and words, the Iranian people have played the role of unconsulted observers. They sympathize with the Gazans for the death and destruction that they have suffered but are outraged at the huge sums their government is spending on militias in Lebanon, Iraq, Gaza, and Yemen, and in propping up the Syrian regime, while neglecting its own people at home. For most Iranians, economic conditions are dire. Inflation is soaring; the cost of living is high, and a large part of the population cannot make ends meet with the meager salaries they earn.

At the same time, Iran is increasingly a police state, along the lines of Russia and China. Dissent and criticism, whether religious, political, or economic, is crushed. Citizens are monitored. Stubborn dissenters end up in jail; some are executed.

This past week, Hassan Rouhani, a former reformist president who was barred from running for a seat in the Assembly of Experts, published an open letter protesting his exclusion. The Assembly of Experts is a body composed primarily of senior clerics that will choose the next Supreme Leader. In his letter, Rouhani reminded the people that he has served in the assembly for the past three terms.

In a ‘confidential’ letter, the Council of Guardians, another clerical body that can veto candidacies for the assembly and for parliament, gave Rouhani only the tersest of reasons for not allowing him to run. Rouhani, in an unusually bold public statement, denounced the decision. The current Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, is 85 years old. The next Assembly of Experts, which sits for an eight-year term, is certain to select his successor. Rouhani suggested he was barred from the assembly precisely for that reason. He also warned that the action taken against him is a sign of worse things to come.

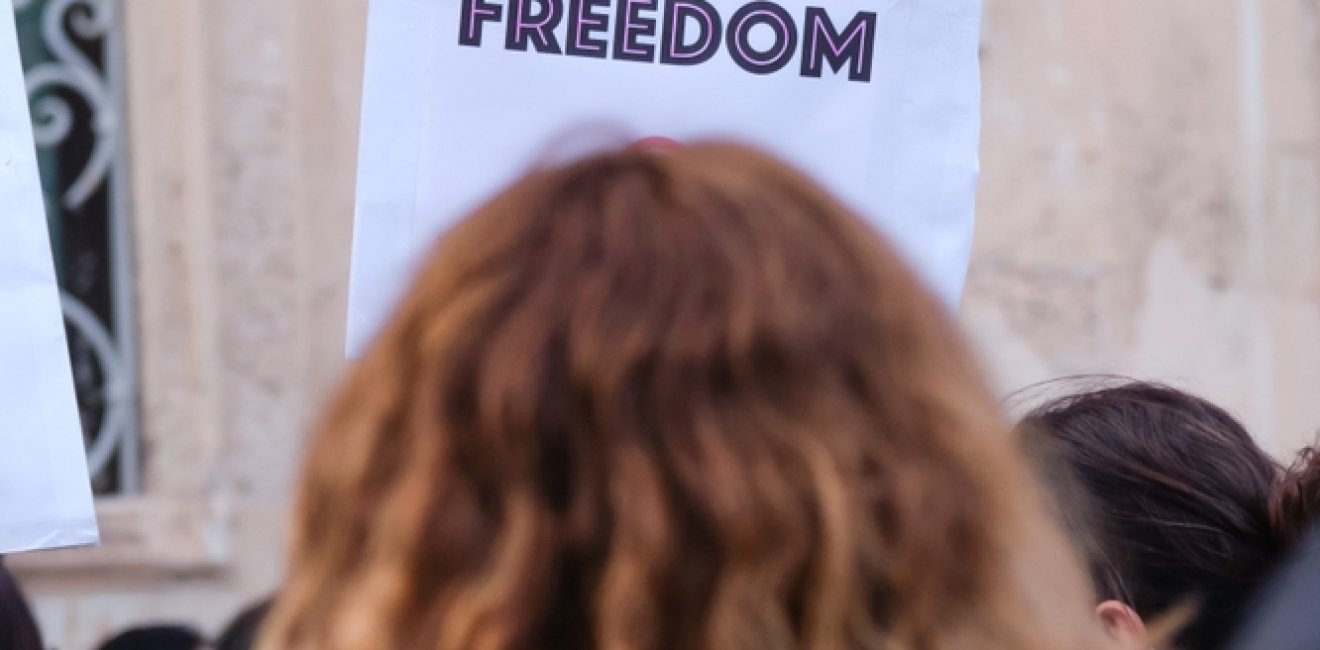

Crackdown on the hijab

As if to distract the people from economic hardship, corruption, and misrule, the government is again focusing on its restless younger generation and on women who do not observe the hijab. The Islamic Republic has waged its hijab war for over four decades with no success. The number of women defiantly ignoring hijab ordinances is growing in larger towns and cities. A friend in Iran commented that, having failed to achieve its domestic agenda—prosperity, equality, the rule of law—“the only thing left from the original promise of the Islamic Revolution is the imposition of the hijab on women.” Another friend in Iran, noting how widely the hijab is ignored, recently told me, “Can they arrest 500,000 women?”

After the uprising last year that followed the death of Mahsa Amini at the hands of the morality police, many thought that, having witnessed a rebellion by the young—the generation that grew up under the Islamic Republic—and their calls for fundamental change, the government would compromise and tolerate women who either wear a modified version of the hijab or none at all. And, in fact, once the uprising was quelled, the morality police were withdrawn from the streets. The streets were calmer, and those women who felt comfortable wearing the hijab continued to do so, while those who sought the freedom to choose put their scarves aside.

But the calm was short-lived. In a speech in April, Ayatollah Khamenei declared the hijab “is a definite Islamic law” and that women had to adhere to it. Barely were the words out of the Supreme Leader’s mouth when the morality police, male and female, were back on the streets of Tehran and other cities. Women not observing the hijab were dragged into parked vans, beaten, and hauled off to prison. Women were warned their bank accounts would be closed, drivers’ licenses confiscated, and cars impounded. Shops that serve women without the hijab were shut down.

The Majlis, or parliament, is about to pass a new law based on the ‘Nour Project,’ which once again will make the hijab mandatory. The morality police started enforcing ‘the Nour Project’ even before it has been enacted by parliament. Has this heavy handedness and punishment cowed women or prevented them from appearing on the streets without the hijab? Not really. These days more and more women continue to ignore the hijab.

‘Nour’ means light in Persian. A friend in Iran told me it was more appropriate to have called the new law ‘tariki,’ or darkness. That would have made more sense.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not express the official position of the Wilson Center.