A blog of the Africa Program

In 2016, there were 56 internet shutdowns across the globe, 180 percent more than in 2015, according to Access Now, a digital rights company. Many were in African countries. An internet shutdown is when a government intentionally restricts public internet access for a period of time in a bid to limit free speech and access to information, often during elections. These shutdowns are typically national but in some cases are limited to just certain regions, as in the recent months-long shutdown in Anglophone Cameroon. Governments typically do not directly restrict internet access, but order telecom operators and other internet service providers to halt their services.

Governments justify these shutdowns by citing national security concerns and fears of the spread of fake election results, however in truth they fear that citizens will organize protests or expose election malfeasance.

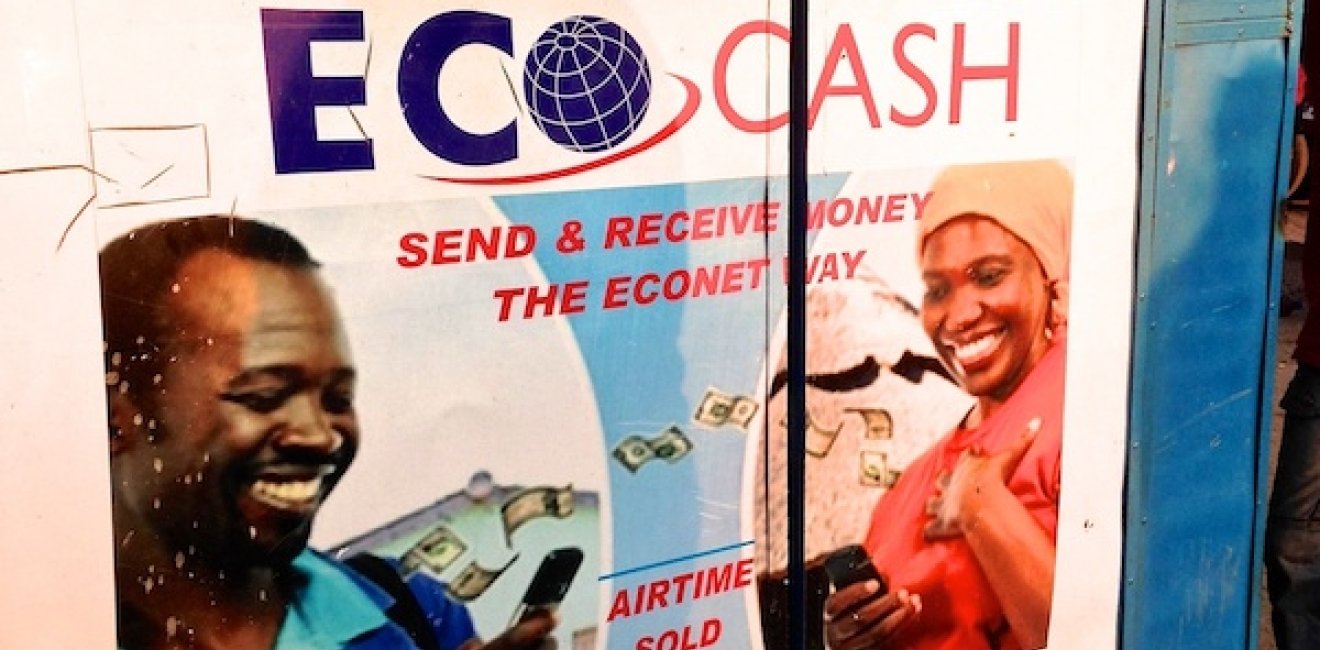

Algeria, Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, the Gambia, Uganda, and Zimbabwe have all shut down domestic access to the internet during elections. Some countries that are considered very democratic have also considered a shutdown: Ghana's Inspector General of Police suggested banning social media on election day, but after a storm of criticism, the government disavowed the idea. In addition to straightforward shutdowns of internet access, countries have also used related tactics to hinder communication. International calls were prohibited in the Gambia during the 2016 election, in Congo television networks were switched off, and in Zimbabwe the state telecommunications authority approved a sharp increase in data prices in January 2017, which would have had the effect of limiting the number of users with internet access as the government faces increasingly widespread protests in the run-up to the 2018 elections.

Justifications for Shutdowns

Incumbent governments often fear protests from the opposition, and takes steps to stop them. In Uganda the main opposition leader was detained by the police four times in eight days during the campaign, and was also placed under house arrest. The police accused him of rallying his supporters to the streets, which he denied.

The internet can be used to organize those protests. Today, social media is a threat to many authoritarian regimes, as the Arab Spring clearly demonstrated. In 2011, Egyptians used Twitter, Facebook, and blogging platforms to lament poor leadership and organize protests against President Hosni Mubarak, which culminated in his ouster after thirty years in power. The Egyptian government did eventually shut down internet access, but it was too late to stop the protests.

Some countries both in Africa and elsewhere have stopped short of full shutdowns, but attempted to curb the flow of information online with laws regulating internet usage. In 2015, Tanzania passed a "cybercrime bill," which concentrates more on limiting the right of expression than prosecuting cybercrime. In Russia, bloggers with more than 3,000 daily readers are required to register and operate under the media regulatory body, which was seen by many as an attempt to clamp down on blogs, which tend to report more openly than conventional news sources. In Kenya, section 29 of the Kenya Information and Communications Act (KICA) on the "improper use of a licensed telecommunication system," was used to target citizens criticizing the government online until a High Court ruled it unconstitutional. And in 2016, during the state of emergency in Ethiopia, posting about the ongoing protests on Facebook was a crime with a penalty of up to six years imprisonment.

Political and Economic Effects

During a shutdown, human rights violations by the state may go unreported. For instance, in Ethiopia several people died during protests, but it went unreported due to government interference in the media and a social media blackout. Indeed, in some countries internet shutdowns have been accompanied by state crackdowns on protests.

There is no evidence that shutting down the internet leads to a free and fair election, whatever the claims of governments that do so, and it's not necessary to hold a successful election (Ghana recently held a peaceful election without an internet blackout). In fact, internet shutdowns can inhibit free and fair elections. Without internet, communication is hindered for journalists on the ground, the public cannot report fraud or irregularities witnessed at polling stations, and political parties and their supporters cannot communicate. In the case of an emergency, the lack of internet access can slow communications between various stakeholders, like firefighters or police.

Moreover, internet access can play a positive role in elections. Politicians and aspiring officeholders use social media to communicate, sell their agenda, receive immediate feedback from their supporters, and advertise their meeting points. It is unfair to citizens for incumbent governments to shut down internet access on election day, after the internet has played a crucial role during the campaign. Elections are a key part of the democratic process, so it is ironic that while exercising these rights citizens often find their freedom of expression and freedom to access information restricted. The spread of misleading information about election results can also be combatted by embracing the internet – in Kenya, the electoral body used its website and social media tools like Facebook and Twitter to share election results and answer questions from the public.

Finally, shutdowns also often have a negative economic effect; a great deal of money is lost as companies cannot transact business online, banks and ATMs stop working, and citizens cannot communicate by email and social media. India's shutdowns cost an estimated $968 million in economic activity, while Saudi Arabia, Morocco, and Iraq lost an estimated $465 million, $320 million, and $209 million in economic activity respectively.

Public Pressure and Action

On July 1, 2016, the United Nations passed a resolution by consensus that condemned intentional internet shutdowns as a violation of Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and argues that the rights to free expression apply online as well as offline.

This is a wakeup call for civil societies to champion internet freedom around the world. Governments can be pressured on the economic damage a shutdown causes. The public needs to be empowered to air their concerns about shutdowns to governments. At the same time, citizens need to be informed that there are limits to the freedom of expression, which typically do not extend to defamation or calls for violence. Responsible use of social media by citizens and fair reporting by media organizations will make it more difficult for governments to justify internet shutdowns.

Africa's internet penetration rate is 27.7 percent, more than 345 million internet users, a number that is expected to rise given the low cost of internet-connected mobile phones. Internet access plays an increasingly crucial role in the functioning of politics and commerce across the continent. Shutting it down will hurt economies and violate citizens' rights, and election time shutdowns will only cast doubts and cause tension about the outcome of the election.

Sharon Anyango was a Southern Voices Network for Peacebuilding Scholar at the Wilson Center from February to April 2017. She is a Communication and Outreach Officer at the African Technology Policy Studies Network (ATPS), a member organization of the Southern Voices Network for Peacebuilding.

Photo: A stand selling phone credit in Zimbabwe. In the past, Zimbabwe has shut down internet access in response to protests. Photo by Kay McGowan, USAID, via Flickr. Creative Commons.

Author

Communications and Outreach Officer, African Technology Policy Studies Network, Kenya

Africa Program

The Africa Program works to address the most critical issues facing Africa and US-Africa relations, build mutually beneficial US-Africa relations, and enhance knowledge and understanding about Africa in the United States. The Program achieves its mission through in-depth research and analyses, public discussion, working groups, and briefings that bring together policymakers, practitioners, and subject matter experts to analyze and offer practical options for tackling key challenges in Africa and in US-Africa relations. Read more