A blog of the Wilson Center

A new report suggests that preterm birth is 16% more likely to occur on heatwave days.

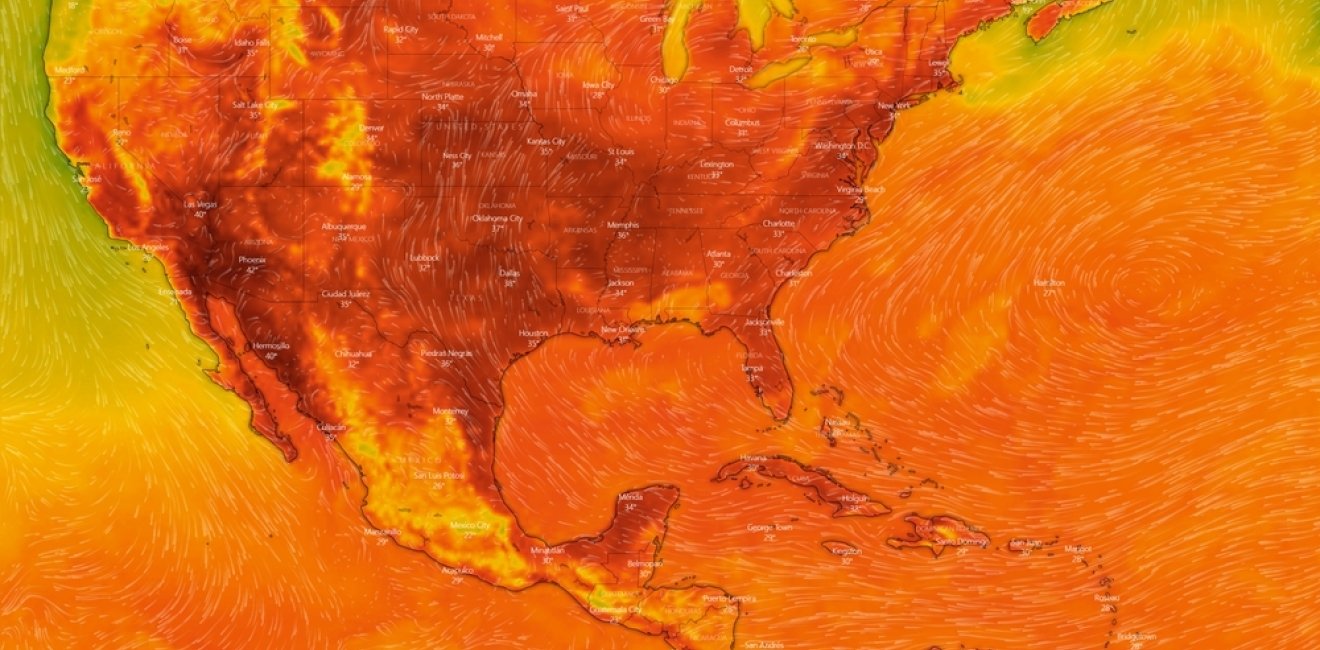

According to data conducted by NASA’s Goddard Institute of Space Studies, worldwide, the summer of 2023 was the hottest on record since 1880. With those rising temperatures, heat-related disasters also seem to be occurring more and more often. From wildfires across Canada to flooding across the Mediterranean, extreme weather events were on the rise.

There’s something else that appears to be increasing with the rising temperatures: premature births. A recent study from Harvard concluded that of the 32 million births in the United States in 2020, nearly every case of premature birth—births at 37 weeks or earlier—was associated with exposure to heat during the pregnancy.

A new policy paper from the Wilson Center’s Maternal Health Initiative, or MHI, sheds more light on the topic. It notes that extended stretches of greater heat have been shown to increase stress levels in ways that can affect fetal development. In addition, the report suggests, extreme heat can lead to conditions like gestational hypertension and gestational diabetes—the type of complications that often lead to preterm births.

Nila Wardani, coordinator of the Research Division of White Ribbon Alliance Indonesia told the audience at a recent MHI event, “A sea level rise has direct impact on pregnancy: it changes the salinity of water due to sea water intrusion. The increase of salinity will increase salt intake that can have adverse effects to pregnancy, leading to an increase of hypertensive disorder.”

Even more than the temperature threshold, a University of California at San Diego study shows that the duration of heightened temperatures—the length of a heatwave, which is defined by the National Weather Service as a period of abnormally hot weather lasting more than two days—may affect the probability of premature birth.

It’s not just the way that higher temperatures directly affect fetal development that is contributing to higher premature birth rates, it’s also the phenomena that can accompany rising heat.

Extreme heat holds moisture and increases the risks of hurricanes and flooding. Floods bring standing water, which attracts mosquitoes and other disease-carrying insects that can cause illness. Many who suffer from malaria, for example, are pregnant women. Flooding also makes it harder for families to travel to healthcare facilities, which is particularly important during pregnancy and the early days of life.

Exposure to smoke caused by wildfire—another phenomenon that becomes more frequent with rising heat—can also be dangerous for pregnant women, as the inhalation of smoke increases the severity of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases in both the mother and the fetus. The State of Global Air report from 2020 found that air pollution accounts for 20% of all newborn deaths worldwide, mostly related to premature births.

An October 2023 Pew Research Center survey found that a majority of Americans believe that climate change is harming the American people, and 63% expect things will “get worse in their lifetime.” The question is: how will those numbers change as public health officials explore more and more the links between climate extremes and poor health—especially for the most vulnerable.

This blog was researched and drafted with the assistance of Carlotta Murrin.

Author

Explore More in Stubborn Things

Browse Stubborn Things

Not-So-Renewable Energy in Zambia

Colombia's Cocaine Moment of Truth

There's Mining, Then There's Galamsey