A blog of the Indo-Pacific Program

Today, we live in a world of increasing democratic backsliding and attacks on free speech are not uncommon. Pakistan is no different–print or media journalists who are perceived to have crossed certain red-lines can face censorship and intimidation while the media houses that employ them could be financially undercut. As the Pakistani state cracks down on the mainstream media, social media has become a bastion of critical voices, but now the Pakistani authorities have turned their attention to social media and bloggers are facing similar consequences.

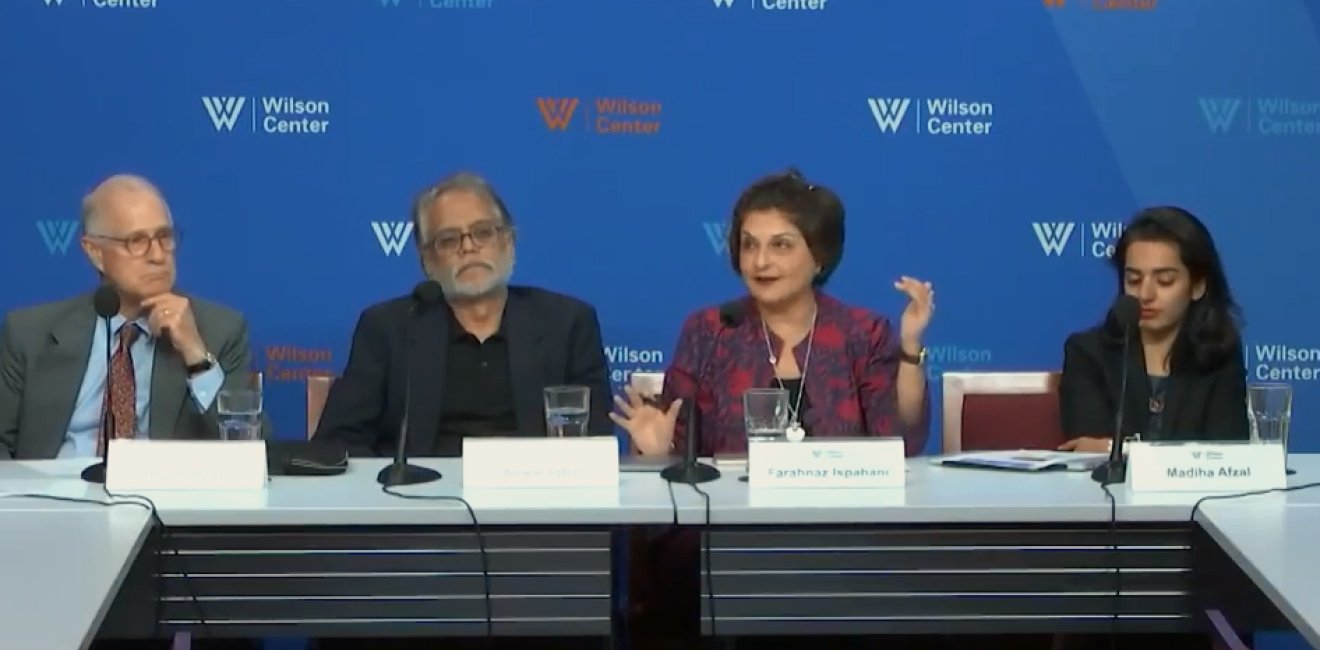

On September 12th, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) launched a report on the plight of journalists in Pakistan today at an event organized by the Asia Program at the Wilson Center. The event kicked off with CPJ premiering a documentary which highlights the acts of intimidation against the Pakistani press through the stories of four journalists: Ahmad Noorani, Fawad Hasan, Hafiz Husnain Raza, and Farzani Ali. It makes the point that many journalists are self-censoring out of fear of the military and government institutions.

Steven Butler, Asia Program coordinator at CPJ explained that the report focuses on problem areas and tries to explain what is going on by looking at the stories of individual journalists. He says it was derived out of a simple of question: there has been a drastic reduction in the killings of journalists since 2014, so then why are journalists in Pakistan reporting even greater levels of censorship and intimidation?

It was his understanding that the process had been set off in 2014 when Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Agency (ISI) did not take kindly to an interview aired on Geo News. The ISI attacked Geo News financially, while many Pakistani media outlets attacked Geo News verbally. According to Butler, “the conflicts within the media…undermined the credibility of the news media as a whole.” In addition to this, when Pakistan’s Military launched the Zarb-e-Azb a campaign to stomp out militancy, the military earned a lot of respect for making Pakistan safer, but also gained direct control of the media in some parts of the country. Butler concluded on an optimistic note stating that there was still room for great journalism as the “pressure has not blunted the courage of many journalists.” Butler dedicated the CPJ report as a “Salute to Pakistan’s journalists.”

Anwar Iqbal, a veteran journalist with the Dawn, shared his perspective as a member of the “Pen Tribe” in Pakistan. To him, the story of journalism in Pakistan was one of success and he said he looks at the situation from a “positive angle.” “From the days of direct censorship, we have reached a stage where those who censor now have to think how to do it,” elaborates Iqbal. “Obviously that control is still there…but the room for defiance is much larger than it ever was.”

Iqbal stated that journalists in Pakistan were threatened not only by the military, but also by the media houses who don’t pay their journalists for months on end. Apart from this, free speech in Pakistan is challenged by terrorist groups, the civilian administration, and political parties, but despite this, Iqbal says journalists in Pakistan are hard to silence.

Farahnaz Ispahani, a former journalist who served as the media advisor to President Asif Ali Zardari illustrated the institutions in Pakistan responsible for censoring the press. Speaking from her personal experiences she stated that even though there is an elected civilian government there are “far too many issues on which the final word remained in the hands of Pakistan’s invisible government and permanent institutions of state.” According to Ispahani, Inter-Services Public Relations, the media wing of the Pakistan’s Armed Forces, issues directives for all the media outlets to follow and control the narrative within the country. She says, “Pakistan’s greatest problem is a desire by the all-powerful institutions of state to maintain a uniform national narrative. This narrative requires journalists to report only what is deemed positive and to adhere to the very strict limits in criticizing the government or the state apparatus.”

Mediha Afzal, a Nonresident Fellow in the Global Economy and Development Program at the Brookings Institution, explained the rationale behind the military’s censorship of the media and how it effects democracy in Pakistan.

According to Afzal, “the purpose of the military and Pakistan’s security agencies in putting pressure on the media is to twofold: one is to maintain military supremacy over the civilian government…and two is also a little bit of political selection.” Afzal added that by pressuring the media, the military is trying to protect its narrative of Pakistan, which is that “Pakistan is an Islamic State and it faces a perennial threat from India.” Any issues that challenge this narrative are censored–for example the Pashtun Tahafuz movement and Baluchistan insurgency cannot be covered by the media. Apart from this, Pakistan’s blasphemy laws are taboo, and so is any kind of criticism of China and the China Pakistan Economic Corridor. Afzal also elaborated on how the military blocks news organizations that go against its narrative–by targeting their distribution network . She added that the blockage of newspapers and TV channels is only partial as it allows the military to “maintain a plausible deniability.” Many journalists have even censored themselves out of a sense of “self-preservation.”

With regard to the effects of the media environment on democracy in Pakistan, Afzal states that the media’s censorship “affects accountability, it affects public opinion and those things are the conduit through which it ends up affecting service delivery and policy.” Hence the effects are huge. However, she says there is hope for free speech in Pakistan, as people have taken to social media to “bring to light things that are not covered in traditional media.” Afzal concludes by stating “the media has a crucial role in affecting public opinion, shaping the political landscape, and affecting policy ultimately.” She refers to instances where the Pakistani media has prorogated conspiracy theories and “problematic paradigms of thinking” and urges the media to stick to “truthful reporting.” She asks the media to “self-reflect and regulate” in order to counter the pressure on them.

View the full event below:

The views expressed are the author's alone, and do not represent the views of the U.S. Government or the Wilson Center. Copyright 2018, Asia Program. All rights reserved.

Author

Indo-Pacific Program

The Indo-Pacific Program promotes policy debate and intellectual discussions on US interests in the Asia-Pacific as well as political, economic, security, and social issues relating to the world’s most populous and economically dynamic region. Read more