The transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

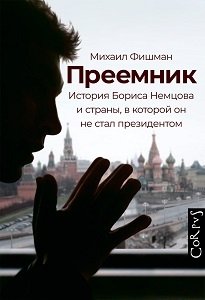

Izabella Tabarovsky: Hello and welcome to The Russia File. I am Izabella Tabarovsky and my guest today is Mikhail Fishman, a prominent independent Russian journalist, broadcaster, and author of a new book, The Successor: The Story of Boris Nemtsov and a Country in Which He Didn't Become President. The book paints a portrait of Boris Nemtsov, possibly the most important opposition politician in post-Soviet Russian history.

Nemtsov was gunned down on a bridge under the walls of the Kremlin in February of 2015. Nemtsov’s story is deeply intertwined with the past 30 years of Russia's history. And it helps us understand many of the issues that we're facing today, including the personality and motivations of Vladimir Putin and Russia's war in Ukraine. In the book, Fishman tells the story of Nemtsov's rise from a region where he was a governor to the national stage, where he attracted the attention of world leaders, from Margaret Thatcher to Bill Clinton.

Many expected him to succeed Boris Yeltsin as the president of Russia, but that is not what happened. Instead, the man who succeeded Boris Yeltsin was Vladimir Putin, and the history of Russia took a very different turn. We're presenting my conversation with Misha Fishman in two parts. This is part one. Misha, welcome to the program.

Mikhail Fishman: Thank you very much for having me.

Izabella Tabarovsky: Your book was published recently in Russian by Corpus. Its Russian title is “Преемник. История Бориса Немцова и страны, в которой он не стал президентом.” The English translation is still being completed, but I really wanted us to have this conversation now, because as I've read the book, I was just struck by how incredibly timely and relevant it is. And so we'll get into it, but I actually want us to start by talking a little bit about your own story and about your background.

Mikhail Fishman: I started as a journalist in late ‘90s, as a political reporter. That's how I knew Nemtsov, because I was following closely his first campaign. I write about Russia and [the] Russian political regime.

Izabella Tabarovsky: And for the last several years, you've been on TV Rain. And TV Rain, of course, is a really important independent television channel in Russia, [and] was persecuted heavily in itself. And you were there on the morning of February 24th, when Vladimir Putin declared war on Ukraine. What was that morning and day like?

Mikhail Fishman: I anticipated this war. I was talking about it on my shows every Friday, starting from December. I was anticipating it and I knew that if it [came], it would change everything, of course, including my own life. Wars always come together with a tightening censorship grip, so I knew TV Rain would not survive. I was morally ready, but yet you can never get ready [for] a morning like that and to what happened on February 24th.

It came as a shock, this news of [the] Russian military shelling Kharkiv and shelling Kyiv and starting its first assault on Kyiv. I had my show the next day and during these first days, there was little doubt that Putin [would] actually capture Kyiv. And yet I claimed in my first wartime show that Putin ha[d] already lost this war, because it's impossible to win a people's war and for Ukrainians, it's a people's war. And he would never be able to control Ukraine anyway, even if he does conquer it, and does capture Kiev, and Zelensky fled.

Izabella Tabarovsky: How long did TV Rain manage to stay on air before you were shut down?

Mikhail Fishman: A little bit more than a week. I was on air live. It was March 1st. It was at around 8 p.m. I was live, talking about what was going on in Ukraine. It was really horrible. And at that very minute, TV Rain’s website was blocked by [the] Russian official media watchdog. And at that very moment, we all knew: that's it, that it's over, that TV Rain would not survive this time. And during next couple of weeks, I guess every independent media outlet in Russia was shut down.

Izabella Tabarovsky: When and how did you know that you had to get out of the country?

Mikhail Fishman: I left the country the next morning. It was a very sensitive moment, that evening on March 1st, when the website was shut down; nobody knew what's next. The new legislation banning even calling this war a war was already introduced [in] the parliament and it was clear that once it [was] signed by Putin, it would be used as a tool to repress every independent voice about this war. So I left the next morning. That's when the majority of Russian independent journalists left.

Izabella Tabarovsky: So where are you now?

Mikhail Fishman: First, I flew with my wife and daughter to Baku, in Azerbaijan. We wanted to get to Georgia, but I was denied entry to Georgia, me personally. So we found ourselves stuck in Baku for a while and then managed to get to Israel, where I am now, for more than three months already.

Izabella Tabarovsky: A fairly typical story in many ways, unfortunately, for a lot of Russian independent journalists who try to leave the country.

So let's talk about the book. I want to ask you: why is it important for people to read a book about Boris Nemtsov now?

Mikhail Fishman: The book is called The Story of Nemtsov and of the Country Where He Didn't Become President. And it's a meaningful title because it's not only about him. It's a journey, I would say, together with Nemtsov through Russia's history from the starting point, from when Russia emerged after the Soviet Union collapsed. And the idea of the book is that [the] story of Nemtsov as an individual, as a political leader, as a person, is the story of Russia. And I do not separate one from the other. And Nemtsov’s fate, if you will, his career, his path represents Russia’s path, what Russia went through.

If not [for] Gorbachev's perestroika, Nemtsov would never [have] enter[ed] political life to start with. His success story of the first half of the ‘90s and his failures of the second half of the ‘90s, the Yeltsin era, reflect the dramatics of that time, and of course, it was inevitable that he would oppose Putin, which happened when Putin came to power.

And I have to say that Putin's invasion of Ukraine proved this idea to be right. I mean, that this fate is Russia's fate, that's the idea of the book. And Nemtsov was murdered in early 2015, during the first phase of the war in Ukraine. And it was the first phase of the war in Ukraine that had him killed; we can elaborate on that if you wish. And then, seven years later, the same war is killing Russia right in front of our eyes. Not only Ukraine. Of course, Ukraine is the main victim, but Russia is that, too.

Izabella Tabarovsky: Exactly. And as I was reading the book, I kept thinking just how relevant so much of it is. You see the roots of what we are seeing today, you see [them] in that history that you are telling and in those stories that you are telling. So I wanted to ask you, how did the book come out in the first place? Why did you decide to write it? It's not your first time that you immersed yourself in the story of Boris Nemtsov.

Mikhail Fishman: No, not the first time, but usually it's the opposite. Usually, books turn into movies. But we made the movie first. A few months after Nemtsov was murdered, I was approached as a political journalist—who knew Nemtsov and who shares the same values as Nemtsov did—to write some sort of a script for a film about Nemtsov.

And it took us a year and a half. And Vera Krichevskaya and I, we made a film about Nemtsov and about Russia. That's when I got grabbed by this idea that Nemtsov represents Russia and its path. That's when I got it. And the film is based on this idea. And then again, I was approached: well, let's turn this film into a book. And I started thinking: well, okay, sure, why not?

Izabella Tabarovsky: And the book was published already after the war began and after the repressions, the crackdown. Was there fear that it wouldn't come out?

Mikhail Fishman: I would add that the book is, of course, much more detailed than the film. It really goes deeper into why, what happened, and what triggered what, and how political life evolved, and why decisions were made as they were made. And I knew that I was late. That's the irony of history: that I had to leave Russia, but my book actually made it to the bookstores and came out in early April and is available across Russia, basically in every major bookstore. And that's very ironic.

Izabella Tabarovsky: It's very ironic. And it's also excellent news. And I should say also for our listeners who do read Russian that you can get this book electronically.

Let's delve into the book. And I want us to start by talking first about Nemtsov as a person. So if you were to describe him as a person, what characteristics would you name as the most important and prominent ones? And also, what was important for him personally as a human being and as a politician? What were his values?

Mikhail Fishman: Nemtsov is a very specific political leader because he is very bright; he is very open, loud, and handsome; and a charismatic type of person. And cherishing liberal values. This is obvious from the very start. He was a true Westerner. He was a true believer in Russia as a part of Europe and [the] global world.

I'd say his most important quality, which actually made [him what] he became—the symbol of free Russia—I think it's his honesty. That's his main quality. He is honest, open, transparent, and not corrupt, from the very start to the very end. And this is crucial, I think, because Russia's biggest problem, [which] led to Putin's rule and then to his tyranny and now to this, is [the] Russian elite’s weakness and irresponsibility and appetite for corruption.

And Nemtsov was different. He had this core within him, inside him, that never in his life, never through his political career,…be [it] his time [as] governor or when he was in Russia's government or later, he was always incredibly scrupulous and nothing ever stuck with him; [there was] nothing dirty in his career. I don't really know any other political leader like that in Russia.

Izabella Tabarovsky: Well, and it's interesting you tell a story in the book (and also I think that episode appears in the film) [about] when in the very early years there is a debate on TV and all of the politicians are promising something and he says something very different. What does he say in that episode that won the audience over?

Mikhail Fishman: It's the first election of the members of the Russian Council, parliament, let's say, [the] first really free election in Russia. Some kind of debate. And then Nemtsov was what, 30 years old, and he looked, again, different from any other candidate at this debate because these were representatives of the still Soviet elite. And he was young, handsome, with big curly hair, not even wearing a suit.

And then he goes, “so many people around here say so many beautiful things, and I will just say one thing: I won't lie.” And it actually worked. Nemtsov really understood how to connect with those people. And people called him later, in Putin’s era he had this label of being a populist. But what is populism? “I am a populist,” Yeltsin said in [the] very early ‘90s or late ‘80s. Because this is what makes me different from all these Soviet leaders who are disconnected from the nation. And that was also true [for] Nemtsov. He never lied, tried not to lie. And he always wanted to make sure that he is heard and his message is clear.

Izabella Tabarovsky: And it's interesting, because I think in many ways, Nemtsov as a politician would actually be really understandable to Americans. And maybe that's why Westerners really connected to him and really liked him. But, you know, Americans say that all politics is local, and Nemtsov really did begin his political career locally, really wanting to make sure that—as you say, some would call it populist—but he really wanted to help the people of his region, the Nizhny Novgorod region. And so he didn't grow out of corruption or out of buying influence, as you say. He really grew very naturally from the bottom, from the grass roots up. And it was something very rare and unique in those early post-Soviet years, and for Russia in general.

I wonder if you can tell us just one story of his achievements, his local achievements. And there’s that story of the building of, I think you say, 5,000 kilometers of roads in the region. And what did he do to check their quality? Because I think that that story illustrates something really important about him and about how things work in Russia.

Mikhail Fishman: The year is 1994 or 1995, something like that. And as a governor, he had to check the newly constructed roads [so] he put a glass of vodka on the car. And if it didn't splash while he was driving on this road, then he approved the road. And of course, again, this is a PR stunt. Of course, it's a gesture designed to show that it's a people’s program. It's a project designed for people because we know that Russians drink vodka.

But again, he was, as a governor, truly connected with people. He was a reformer. He started privatization. He started agricultural reform. And what also made him different from many others is that he was very open and accessible to people. He cared about people and he was very accessible.

Izabella Tabarovsky: And again, it's such a contrast with the Soviet years, and that's what made him really stand out.

Another really important theme of the book—and it was also…important…[in] your film—[is when you] called Nemtsov a man who was too free. So the question of freedom, because freedom was really important for Nemtsov. And I think you say that the early years of Yeltsin's rule were a period when Russia had real freedom of a kind that Russia had never had, except maybe for the period of February through October of 1917. The problem was that freedom had won, but democracy hadn't. Can you explain that?

Mikhail Fishman: Yes. Well, as a researcher, as a journalist, I was so much enjoying writing about [the] early ‘90s, because it was truly the time when Russia was free. Imagine that after 70 years of Soviet rule, Russia truly becomes a free country. It starts, of course, as we all know, under Gorbachev, with glasnost. Russia's freedom starts as freedom of the press, but then it evolves. Freedom of the press, freedom of conscience, every private freedom you can imagine, freedom to earn as much as you want, freedom to go wherever you want—something that Soviet people could never even dream about. And the free elections from 1990 until 1996, let's say, every election on the federal level was totally free of any kind of governmental, federal pressure. Yet, democratic institutions were weak to start with. And second, and very importantly, nobody understood what democracy actually is.

Well, to give you an example, electing Yeltsin in 1991 as Russia's president: that was a truly historic moment, because never before [had] the Russian nation elected its leader. Yet during this very symbolic, very representative, very historic election, there was no real competition, because everybody understood that Yeltsin would win and Yeltsin in the first place knew that he would win.

So, there was an assumption back then that it's enough to elect a leader who would enjoy public support, as Yeltsin did, and that would lead us to democracy. If you trust your leader, if the nation trusts its leader, it is democracy. But it's, of course, not that simple. That's what we know about much more now, because we learned during these decades what democracy is, how it has to be grass-rooted, how institutions actually work, what are institutions of power, what are checks and balances. Nobody knew that in Russia. And that's what Russia was. It was free, but democratically, it was not established.

Izabella Tabarovsky: So let's talk about Nemtsov's relationship with Yeltsin, because when we talk about the successor, that's who Nemtsov was supposed to succeed. He was supposed to become the successor to Yeltsin. And Yeltsin and Nemtsov were famously close. How did Yeltsin notice Nemtsov and bring him close? What attracted Yeltsin to Nemtsov?

Mikhail Fishman: Well, the year again is 1991. Imagine Nemtsov, as we already described him: loud, visible in any company, very handsome, bright, big as a person, [the] kind of individual that you always notice if he's in the room. So they connect during the coup, Nemtsov and Yeltsin, because they were both in the Supreme Council’s building, which became the headquarters of the resistance.

Izabella Tabarovsky: And you're talking about August of 1991.

Mikhail Fishman: Yes, August 1991. And after the coup failed, the question arose [about] who Yeltsin would appoint as head of [the] Nizhny Novgorod government. Because before that it was a communist government in Nizhny Novgorod and these communist authorities supported the coup and were dismissed. And Yeltsin knew nobody, so he appointed Nemtsov and, as Nemtsov recalled himself, gave him a chance. “If you manage well, I will let you work. If you [do] not, then you will be fired.” So that’s how their relationship started in August 1991. And in December 1991, Nemtsov was appointed head of Nizhny Novgorod.

Izabella Tabarovsky: I want to ask you, at what point, is there a specific point when Yeltsin realizes that he views Nemtsov as a possible successor?

Mikhail Fishman: He liked him from the very start. I think that he connected with him on a personal level as well, because Nemtsov was anti-bureaucrat. He was very different in his style and in his approach. And yet he was loyal basically to Yeltsin, though he [did] not always vote as Yeltsin asked him [to]. But he never crouched, he was always full of his own personal dignity. And that's what I think Yeltsin also liked about him. But what happened politically was also important, because while Yeltsin's government was losing its support, Nemtsov was sort of [on the side]. He was a reformer, he was doing his own reforms in Nizhny Novgorod, but he was on his own, and he was not seen by the nation as responsible for all these difficulties and problems and all the struggling that the nation had to go through during Yegor Gaidar’s reforms.

So while reformers on [the] federal level were going down, Nemtsov was going up. He was very popular; by the end of 1995 I guess he was probably one of [the] two, three most popular governors across Russia. He was a national phenomenon. So for Yeltsin, politically, it was very obvious, I would say, to stick to Nemtsov as a possible successor because he [was] on the same page with him. He [was] part of his larger team, yet he [was] still reliable politically. He once met with Clinton in, I guess it was 1993. And even at that time, he [had] already pointed at Nemtsov as his possible successor.

Did he really believe in it? We will never know. But in [the] 1990s Nemtsov comes to Moscow from Nizhny Novgorod as a part of Yeltsin's government. Yeltsin, of course, has in mind that Nemtsov is most likely next Russia's president.

Izabella Tabarovsky: I do want to ask you about this idea of a successor….We talked a little bit about how in Russia freedom had won, but democracy didn't. Still, the idea of a successor is actually deeply undemocratic. Yeltsin was a democrat. He really believed in democracy. I think that's pretty clear. So why did he need a successor? Why couldn't he just let the nation decide the next president in an honest and open election?

Mikhail Fishman: Yeltsin, I would say, wanted Russia to be part of a global, civilized world and a democracy. But he probably didn't know what democracy is. He didn't really understand it. He understood about freedoms. He understood about [the] Soviet past. He understood about [the] KGB. That he knew. But what is democracy? He probably never fully understood.

And yes, of course, you're totally correct. The concept of [a] successor is undemocratic by nature. Because it’s not up to the ruler to pick the next one, right? It's for the nation to decide. But the problem of succession in Russian politics is, of course, deeply connected to the political climate in Russia from the early ‘90s. Basically the same thing that I already said, that democracy didn't work. Freedom yes, existed, but not democracy.

What happened? And that's the tragic development of Russia. That's this first misstep on Russia's path to freedom and democracy. The misstep that happened on the first day, when Russia actually emerged as a new country after the collapse of the Soviet Union, is that political life turned into a zero-sum game between political actors, notably between the president and the parliament. They started a fight on what Russia's reforms should look like. Until Putin came to power and suppressed the parliament as an institution, it was the fight, the political battle in which the winner takes all.

Democracy isn't supposed to work like this. Democracy is supposed to work very differently. If you lose in the election, it doesn't mean that you lose your resources, your influence, your financial capital, your freedom, or even life. It means that you just don't have power anymore, but everything else is still with you. But in Russia, the stakes became so high from the very start.

If you cannot actually lose an election comfortably, that means that you need a successor. And that's how the idea of [a] successor actually emerges. If you're always fighting and the stakes are so high, you need to secure your future. You cannot [separate] democracy from your personal future in which you won't be at the helm. That's why you need a successor who [will] secure your own position.

Izabella Tabarovsky: Well, and of course, we know that the eventual successor was Vladimir Putin. It wasn't Nemtsov. And that's what makes the story that you tell so poignant, because it's impossible to read this book without asking yourself the whole time what might have been. How different would Russia be today if Nemtsov, in fact, had become the successor?

Mikhail Fishman: Putin was chosen as the successor on the same motivation. The motivation was the same. He had to secure the path and also the future of those who picked him as successor. And you couldn’t tell one thing from the other. That's why he was a success.

Izabella Tabarovsky: Exactly. I want us to talk about the First Chechen War. It occupies, Chechnya in general occupies, a significant part of the book. And I want us to talk about it because there are lines that go from that war—[the] second war as well, but especially the first war—to Russia's war against Ukraine today, as it seems to me. The First Chechen War was one of the pivotal moments in Russia's post-Soviet history. And in fact, you say that Chechnya became Russia's Vietnam. Can you explain why?

Mikhail Fishman: Nobody expected the war in Chechnya to turn into…[the] horrific war it actually was. It was thought of as a military operation that would last for two months, maximum, and then it [would] be over. Nobody could even think [of the] kind of resistance that Dudayev and his forces would actually be able to demonstrate. And it turned into a really horrific war, which took [the] lives of tens of thousands of inhabitants in Chechnya and of thousands of Russian soldiers.

Its political [effect] was huge. It led to the Second Chechen War, and it designed Russia's future. Yeltsin lost this war. This war turned into a defeat, and this defeat grew as a syndrome inside the national conscience. This defeat certainly gave a boost to [the] overwhelming frustration and ressentiment which became Putin's political platform. We can put it this way. So that's to make [a] long story short.

Izabella Tabarovsky: I hear journalists who covered that First Chechen War say that Russia's war in Ukraine today really reminds them of that war, in terms of the level of destruction, the mass murder of civilians, even what you already mentioned—the expectation that it will be a blitzkrieg, and a completely unrealistic assessment of Russian military strength. Do you see similarities like that between the two?

Mikhail Fishman: When we talk about similarities between what's going on in Ukraine and the war in Chechnya in 1995–1996, similarities are obvious. As we started, Putin's blitzkrieg, which failed, and the war that he believed would last a month and he would control Kyiv in a week turned into what we see now—a protracted, horrific military campaign.

And the same [is] how the war in Chechnya started, because, as I said, nobody believed it would last that long, even in Chechnya. But it's not the only similarity, of course, because military experts and human rights watchers…see many similarities in the war crimes of the Russian military in Ukraine now, and they see them as a repetition of the same criminal actions in Chechnya in mid-‘90s and then later in the second war in Chechnya. And this is the same logic, the same tactics, the same destroying cities, slaughtering civilians, torture, humiliation, rape, and everything we know about this war in Ukraine, of course, [that] happened back then. But there are many, many differences as well.

Izabella Tabarovsky: Well, and one of the key differences in Russian society then was that there was an anti-war movement, which Nemtsov was one of the leaders of, if not the leader of. The soldiers’ mothers were able to protest and they played a massive role in turning the public opinion around. Why don't we see that today with Ukraine?

Mikhail Fishman: This is a very good question, and I'm not sure that I know all the answers, because it's very hard to understand why mothers of this war—which already [has taken] Russian lives on a much bigger scale than both wars in Chechnya combined—it's very hard to understand and explain why mothers keep silent when we know how it works.

We know that now Russia's government is able to pay money officially to those who lose their relatives in that so-called “special military operation” in Ukraine. But it doesn't probably give us all the answers. I think what is important also is that in [the] mid-‘90s, when the first war in Chechnya started, Russian society was very different. Remember, Russia had free press. Russia was free as never before. And everything made news; television was free, [and] it was reporting from Grozny, from Chechnya. And the war itself, across the nation, was perceived as the war against freedoms and all political parties back then—liberals, but also leftists and communists—saw the war as an authoritarian step against Russia itself. And big rallies against the war….And that was a very different climate from what we have today, after 20 years of Putin’s propaganda. Propaganda actually works, as we know now

Izabella Tabarovsky: This concludes part one of our discussion of Mikhail Fishman's book, The Successor: The Story of Boris Nemtsov and a Country Where He Didn't Become President. Please stay tuned for part two, where we will talk about the relationship between Putin and Nemtsov, Nemtsov's relationship with Ukraine, and what it all means for the contemporary moment.

From the Kennan Institute, this is Izabella Tabarovsky. Thank you for joining us and we will see you on our next episode of The Russia File.