On January 2, 1957, Allan Gotlieb arrived in Ottawa to begin his career in government. He was “off the boat” from Oxford University, where he had lectured in law. Now, like other young strivers, he was joining the Department of External Affairs.

He was charmed by the neo-Gothic Parliament Buildings and intrigued by The Department, as it was reverentially known. But that was all. Indeed, Ottawa appalled Mr. Gotlieb, who saw “an unkempt, decaying village” so dismal that “to call it provincial would have been a compliment.”

On his first anniversary, he wrote a note to himself. Sealed in an envelope and left in a drawer, it read: “Allan, if the day comes when you say to yourself, ‘I like Ottawa,’ that’s the time to leave. It won’t be because Ottawa has improved. It will be because your standards have deteriorated.”

Standards defined Mr. Gotlieb. In a cosmopolitan, consequential life of nine decades that ranged from public service to the arts and philanthropy, he had standards of language, decorum, conversation and performance. He had standards of elegance and excellence. He had standards of art and literature, particularly in 19th-century prints and Victorian tiles, which he collected.

He had standards for others, especially those around him. Most of all, he had standards for himself.

Almost 25 years later, as he prepared to go to Washington as ambassador late in 1981, Mr. Gotlieb retrieved his personal cautionary note. By then, he had served five years as undersecretary of the foreign ministry, 13 years as a deputy minister in two lesser departments, six years in other positions. Although his departure was less about Ottawa than opportunity, he was, in his way, keeping faith with expectations – fulfilling the dream of his life.

In Washington, where he was ambassador longer than any other Canadian, Mr. Gotlieb demonstrated his full suite of talents. His star turn on the Potomac was the climax of a dazzling career. Discarding traditional diplomacy for innovative public advocacy, he helped forge landmark agreements with the United States on free trade and acid rain. He changed the game there and for Canadian envoys in other capitals. Effective as he was in Ottawa, it was that feverish season in the twilight of the Cold War that brought him to prominence. It made him, to historians, colleagues and observers, the leading mandarin of his generation.

Janice Gross Stein, the eminent political scientist who edited a volume of essays in 2011 in Mr. Gotlieb’s honour, hails his “revolutionary contribution to the theory and practice of diplomacy in the last 30 years of the 20th century.” Jack Granatstein, author of The Ottawa Men, places Mr. Gotlieb in the company of Norman Robertson, Hume Wrong, Graham Towers, Clifford Clark and Robert Bryce, who built Canada’s public service.

As their intellectual heir, Mr. Gotlieb was wry, tough, owlish and eclectic. His eyebrows were electric. His humour was dry. His mind was Talmudic. He was a lawyer, by training, but also a diarist, essayist and aesthete. A secular Jew, he climbed the ladder of what was, in his early years, a white, male, Anglo-Saxon foreign service. “He was not afraid to speak truth to power,” observes Daryl Copeland, an unorthodox former diplomat who wrote Guerrilla Diplomacy.

Mr. Gotlieb died in Toronto on April 18, at age 92. He had cancer and Parkinson’s disease.

Allan Ezra Gotlieb was born into an affluent family in the south end of Winnipeg on February 28, 1928. After two years at United College in Winnipeg, he went to the University of California at Berkeley and to Harvard Law School, where he edited the Law Review, and then to Oxford, as a Rhodes Scholar. At every station, he recalled later, “I dreamed of becoming Canadian ambassador to the United States.”

No wonder, then, that he chose public service. A generation ago, government – rather than law or business – was the place for those who wanted to change the world.

In the beginning, he was a legal expert at External Affairs. He served at Canada’s Permanent Mission to the United Nations in Geneva as well as the Conference on Disarmament between 1960 and 1964. He led the legal division at External Affairs in 1967 and 1968.

After a decade in government, he was made assistant undersecretary of state for External Affairs. As historian John English tells it, the ambitious Mr. Gotlieb had aligned himself with the rising Marcel Cadieux, then undersecretary. Both were outsiders. As Mr. English notes, Mr. Gotlieb was “not just intellectually impressive but a shrewd player of the power game as well – a man to be watched, if not imitated.”

Mr. Gotlieb impressed Pierre Trudeau, then minister of justice, who asked him to chair a task force on the constitution. In early 1968, he wrote Mr. Trudeau evoking Canada’s moral obligation as a traditional mediator. The personal memorandum illuminated Mr. Gotlieb’s sense of the country. “What makes the decline of this role particularly serious for Canada is that it played an important part in forging our unity in the post-war era,” he wrote. “Like the Danes who made good furniture, the French who made good wine, the Russians who made Sputnik, Canada, as a specially endowed middle power, as the reasonable man’s country, as the broker or the skilled intermediary, made peace.”

His ascent continued. Mr. Gotlieb was appointed deputy minister of communications, then deputy minister of manpower and immigration. He returned to External Affairs as undersecretary in 1977, where he sought a more coherent foreign policy. As he departed for Washington, Mark MacGuigan, the foreign minister, telegraphed all Canadian missions that Allan Gotlieb had “set his stamp on an era of Canadian diplomacy.”

Relations with the U.S. were strained over Canada’s interventionist policies on foreign investment and energy. Self-assured as he was, Mr. Gotlieb worried how he would do. “Abroad, an ambassador is a salesman, promoter, public-relations operator, huckster, animateur, impresario and lobbyist,” he wrote. “But one thing he can’t be: a bureaucrat or ruler of the desk. This is what I have excelled at.”

Mr. Gotlieb need not have worried. He and his wife, Sondra, whom he had married in 1955, launched a charm offensive that made the residence the most coveted invitation in Ronald Reagan’s Washington. Sondra was tart, frank and at times embarrassingly undiplomatic. Unfailingly loyal, Mr. Gotlieb recovered for her gracefully.

In a capital where Canada’s voice had been unheard, the Gotliebs drew senators, cabinet secretaries, publishers, actors and spies to their table. Two years after his arrival, his dance card full, he crowed that he knew everyone and everyone knew him. The embassy was Washington’s salon. And Ms. Gotlieb was writing a mischievous column in The Washington Post, chronicling who was up and down in “Powertown.”

When Brian Mulroney took office in 1984, Mr. Gotlieb thought he would be fired. Mr. Mulroney kept him on. On his 57th birthday in 1985, Mr. Gotlieb gushed to his diary: “I sense I am at the height of my powers and effectiveness. No doors are closed to me in this town. It doesn’t get any better. If this be vanity, so be it.”

He would use that influence to advance the biggest issue of the day: the bilateral free-trade agreement. It took mastery of the complicated process of decision-making, whose rules Mr. Gotlieb codified in his slender book ‘I’ll Be With You In a Minute, Mr. Ambassador.’

At root was a belief in public diplomacy, pressing Canada’s case not just at the State Department but in the halls of Congress and the welter of government agencies. He created a congressional relations office to track legislation affecting Canada, follow political trends and lobby legislators. This was new for Canada.

“No one had better antennae and greater capacity to turn intuition and intelligence into action,” recalls former ambassador Paul Heinbecker, who served in Mr. Gotlieb’s embassy. “Without Allan and his keen sense of the possible, there would have been no free-trade agreement, a radical idea at the time.”

William Thorsell, former editor-in-chief of The Globe and Mail, calls Mr. Gotlieb “the consummate impresario of the Canadian-American relationship in the 1980s, creating historic benefits for this country. His successors study him still. What better tribute?”

As the Washington merry-go-round turned, Mr. Gotlieb scribbled furiously. Years later, he lamented that his diary was all about “acid rain and softwood lumber.” Published in 2006, the 613 pages (half its original length) of The Washington Diaries 1981-1989 are perceptive, biting and funny.

Mr. Gotlieb had detractors. Colleagues at External resented how little time he had spent in the field; many actively disliked him. He had a testy relationship with Michael Pitfield, the clerk of the Privy Council. A prominent politician who appears in the diary says his depiction is “fictional.”

For many, the memories are sweet. As a junior officer who arrived shortly before Mr. Gotlieb became ambassador, Peter Boehm recalls that a summons to Mr. Gotlieb’s office to explain a memo destined for the minister “was a moment of transcendent fear and intellectual exhilaration.”

In 1989, Mr. Gotlieb left Washington for Toronto. A companion of the Order of Canada, he became chair of the Canada Council and Sotheby’s Canada, publisher of Saturday Night and a legal counsel. He sat on corporate and cultural boards, and continued to collect surrealist books, and prints by James Tissot, which were donated to the Art Gallery of Ontario.

In elite circles in Ottawa, Washington, Toronto and places in between, few were untouched by the worldly and urbane Mr. Gotlieb. Mr. Thorsell, running the Royal Ontario Museum, saw “a serious man of culture who, with Sondra, sparked the life of the mind." Mr. Boehm, who himself reached the heights of the bureaucracy before entering the Senate, recalls a pragmatic visionary who wanted “to build character and to imbue us with the sense that we could do anything and everything.”

Mr. Gotlieb leaves his wife, Sondra, and children Marc and Rachel. His daughter, Rebecca, predeceased him in 2003.

The opinions expressed here are those solely of the author.

This article was originally published in The Globe and Mail.

Author

Associate Professor of Journalism, Carleton University

Canada Institute

The mission of the Wilson Center's Canada Institute is to raise the level of knowledge of Canada in the United States, particularly within the Washington, DC policy community. Research projects, initiatives, podcasts, and publications cover contemporary Canada, US-Canadian relations, North American political economy, and Canada's global role as it intersects with US national interests. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

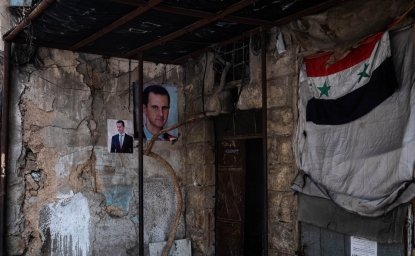

Assad's Reign Ends: Rebel Forces Overthrow Decades-Long Rule in Syria

Любовь до гробовых