Below are responses from several of our experts to Trump's announcement to impose tariffs on Mexican imports.

Duncan Wood

President Trump’s attempt to force Mexico into taking further action on Central American migration seems to be driven by domestic political concerns but risks being counterproductive in a number of ways. First, Mexico is already straining to maintain its current efforts to curb Central American transmigration and is probably incapable of doing any more. In fact it may reduce the willingness to continue to stop Central American crossing the border from Guatemala. Second, Mexico is likely to enact retaliatory tariffs which will hit key Trump constituents such as farmers. Third, Mexico has just begun the process of ratification of the new USMCA accord and this is likely to dampen enthusiasm considerably.

Lastly, AMLO will ultimately have to react to domestic political pressures and adopt a more forceful attitude when responding to the US. This far he has been overly compliant but his patience will be sorely tested by this announcement, particularly because of the recent withdrawal of Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminium.

Rachel Schmidtke

President Trump’s statement regarding emergency measures to address the border crisis contains a series of claims that bear further inspection. The first is that Mexico is not cooperating on enforcement. On the contrary, Mexico has been deporting migrants since 2014 and the trend has been increasing since January of 2019 from 5, 585 returns in January to 9,120 in March. While Mexico could scale up their enforcement strategies to a certain degree, there is neither the institutional capacity nor the political will to deport all migrants that enter through Mexico’s southern border. The U.S. relies on the cooperation of the Mexican government for enforcement; threatening Mexico with tariffs could jeopardize Mexico’s willingness to cooperate further. Instead of punitive measures, both countries need open dialogue to agree on practical enforcement goals.

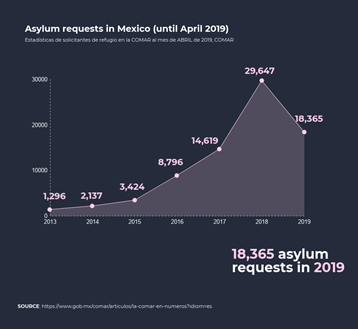

A second claim is that the U.S. the only country whose systems are under strain because of increased flows of migrants. Mexico is also a receiving country for migrants and asylum seekers. Mexico’s refugee agency the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR) recently appealed to the United Nations for additional resources, as the agency struggles to handle the increase of asylum requests, which in the first four months 2019 have surpassed the total number of claims since 2017. The COMAR is in need of more resources so that Mexico can absorb more asylum seekers into the country, which could reduce some of the numbers coming to the U.S. border.

Finally, the White House claims that immigration increases crime rates and overwhelms our social systems. Describing immigration to the U.S. as an invasion that drains the welfare system and causes “untold amounts of crime” is not reflective of the process under which a diverse array of immigrants enter into the United States or their economic and cultural contributions….Not to mention immigrants commit fewer crimes than native-born Americans do.

Christopher Wilson

The White House announced that, as of June 10, the United States would begin imposing a 5 percent tariff on all goods imported from Mexico, with the possibility to raise the tariffs to 25 percent by October if the migration crisis persists. If the United States does go ahead and impose these tariffs, they would negatively affect both the Mexican and U.S. economies, which are deeply interconnected. Approximately half of U.S.-Mexico trade is trade in inputs-- parts and materials that fuel production processes on the other side of the border. Since tariffs are paid by the importing party, this means that an across the board tariff on imports from Mexico is 50 percent a tax on U.S. consumers and 50 percent a tax on American producers. Manufacturers and consumers alike would be forced to pay many billions of dollars in extra taxes, eating away at families’ savings and businesses’ profit margins. Of course the tariffs would be bad for Mexico too. Since Mexico sends 80 percent of its exports to the United States, and since its economy is already growing quite slowly this year, there is a real risk that the tariffs, especially if they were to approach the 25 percent level, would throw the country into recession. U.S. and Mexican officials have worked hard to complete negotiations to rework NAFTA into the USMCA and to find a compromise to remove the steel and aluminum tariffs previously imposed on Mexico and Canada. These developments promised to remove uncertainty and give businesses the confidence to make investments on both sides of the border. Unfortunately the recent tariff threats put those gains at grave risk. In order to avoid such pain on both sides of the border, negotiations are urgently needed to avoid the imposition of tariff.

Eric L. Olson

The immigration challenge that the U.S. is currently facing on its Southern border with Mexico must be placed in a broader regional context. First, we must recognize that Central Americans are fleeing for a variety of reasons but most fundamentally because they no longer see a future in their homelands. El Salvador's president-elect, Nayib Bukele, is reported to have answered the question of why Central American's migrate this way: "They migrate because of lack of hope." They are hopeless because of high crime and violence, lack of economic opportunity, poor education and access to healthcare, but also because of the enormous corruption in their countries. Past and current presidents have been accused of gross corruption in all three countries including money laundering, involvement in drug trafficking, and turning a blind eye or actively encouraging theft of public funds from hospitals, schools, and public works projects.

Until recently, the United States had important programs to improve education; prevent crime; strengthen police, prosecutors, and courts; fight crime and corruption; and create economic opportunities in Central America. These are not perfect programs but many had demonstrated positive results. Yet, many existing contracts have been ripped up, implementers laid off, and U.S. government capacity diminished.

Simply trying to stop irregular migration through punitive measures has never proven effective at the U.S. border and is not likely to work any better at the Mexico-Guatemala border or within Central America. Taking a regional approach to address the drivers of migration is an important but increasingly neglected approach. United States interests would be better served if the U.S. worked to bring together Mexico and Central American governments to develop a comprehensive plan of shared responsibility to address the drivers fo migration. Each country must assume responsibility for its role in this crisis. In Central America, the starting point has to be a recognition that governments have failed to provide their youth economic alternatives, and corruption has eroded the public's confidence in their ability to provide the most basic needs such as safety and opportunity. For its part, Mexico must recognize its role as an immigration destination country as well as a transit country. It must develop policies to address the needs of migrants and resist the temptation to make this someone else's problem. Finally, the United States needs to fix its immigration system from top to bottom. The solution is to create legal and viable pathways for people to work temporarily in the United States, and seek asylum when it’s necessary.

Finally, all countries need to get on the same page regarding a comprehensive investment strategy for Central America. This includes addressing problems of crime and violence, weak government institutions like police and prosecutors, addressing economic despair and hopelessness in the region as critical elements of a strategy to reduce irregular migration from Central America. Mexico’s development strategy for its poor Southern states is important and understandable, but it cannot come at the cost of ignoring the immediate and medium term needs in Central America. It's time for Mexico to take responsibility for expanding development assistance in the Northern Triangle. The U.S. should work with Mexico, multilateral banks and private sources to leverage resources that address the fundamental needs of Central Americans.

Luis Rubio

In whose national interest?

There was a time when the United States understood that its foremost national interest lay in having a prosperous, successful neighbor. That stood in stark contrast with the traditional Mexican perspective, which saw the US as the country’s foremost foe. NAFTA made it possible to align both nations’ interests and helped transform Mexico’s economy into an export powerhouse, benefitting most Mexicans. Clearly, not everything in Mexico is good or even desirable, but there’s hardly a doubt that the country has undergone a dramatic transformation over the past four decades. NAFTA’s renegotiation is far from perfect, but it responds to both the changes the world and technology have brought about, a well as with the political realities of the United States today.

President Trump’s surprising announcement that he would impose tariffs on Mexico’s exports lest Mexico’s government controls immigration flows from third nations raises questions about whether the American policy community understands the consequences his policies might lead to at this particularly harrowing moment for Mexico. AMLO would rather take his country back into the era in which the government controlled society and the economy, a time characterized by far more poverty than anything that exists today.

Mr. Trump’s rationale may well fit into his own domestic political calculations, but it begs the question: does he understand what a radical shift in Mexican politics and political economy that results from his own provocations might mean for his own country and for the future?

Alan Bersin

For the first time in nearly a generation the US Southwest Border is genuinely out of control. We are in this state of disarray because successive Trump Administration policies — zero tolerance, the separation of families, the deployment of active duty military, asylum metering at ports of entry, and a declaration of national emergency in the aftermath of government shutdown — have failed to stem but only exacerbated the desperate flows of Central Americans northward. Nor is the latest policy to which President Trump has lurched — the imposition of tariffs on Mexico — calculated by itself to succeed.

To the contrary, it is a dead end — tantamount to a gun toter’s threat that ‘if you don’t do what I say, I will blow my brains out.’ Tariffs undoubtedly would hurt Mexican exporters but can only do so by visiting much more immediate harm on American consumers who will bear the costs of higher import prices and American taxpayers who will foot the staggering bill of bailing out US farmers.

The silver lining here is that the President finally has placed the right question front and center on the table even if he has threatened an appallingly wrong answer. The fact is that we cannot satisfactorily manage the current crisis without the full cooperation of the Mexican Government. President López Obrador does not want a fight with the United States and has dispatched a high level delegation to Washington to try to avoid one. While Mexico recently has stepped up enforcement efforts at its southern border — reaching levels that succeeded in deterring migrant flows in 2014-2016 — it will need to do more now because of the migrant avalanche unleashed by Trump’s policy incompetence.

But Mexico should come to the table this week armed with a full set of demands on the Administration which it has not presented to date: what assistance and practical measures must the United States Government provide and implement in the short term to make an approach of genuine ‘co-responsibility’ Mexico workable.

Luis de la Calle

The use by president Donald Trump of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to coerce a neighbor, a partner, an ally and its largest market in the world is unprecedented, unwise and counterproductive.

The United States and Mexico face a serious and growing migration problem coming mostly from Central America. This challenge can only be faced jointly and collaboratively. There are no easy or short term solutions. Mexico can do more to improve the infrastructure of its southern border, upgrade its consulate facilities to process visas and offer a generous but orderly migration policy to migrants from those countries. Moreover, much more work needs to be done to foster economic development in Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and southern Mexican states. Mexico, the United States and Canada can work together in developing transportation and energy infrastructure so that this region can have a chance of becoming part of the North American economy and thus grow sustainably.

However, invoking IEEPA will only make things much worse. This Act gives the White House broad powers to protect the integrity of the United States against extraordinary and usual threats. Migration flows from Central America are a very serious problem and a challenge, but not a threat to U.S. national security and integrity. Furthermore, blaming and punishing Mexico for these flows is patently unfair. Rather, appealing to IEEPA appears to be a political-electoral strategy. IEEPA is even worse than section 232 cases, such as the recently repealed aluminum and steel duties, in that there is no investigation of potential injury to a key sector and there is no need for an economic justification for the measures.

Applying import tariffs on imports from Mexico under IEEPA effectively kills the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the new U.S., Mexico, Canada Agreement (USMCA); the negative economic impact will be very large and lasting for both the Mexican and U.S. economies. The initial 5% duty is higher than the original import duties the United States imposed on Mexican goods pre-NAFTA (some 4%); a 25% duty across the board will prove too high for most trade to take place. Mexico’s economy would suffer significantly, but so would the United States’. Mexico is becoming the United States’ largest market in the world and its largest trading partner. Moreover, regional integration in North America offers the best combination for a competitive U.S. vis-à-vis China. In the United States, the impact will be keenly felt in key sectors (agriculture, autos and auto-parts, electronics, medical devices, consumer goods, IPR, telecommunications, IT, electronic commerce) and in critical states (Texas, California, Arizona, the corn belt, the MidWest).

The damage of the proposed duties is so widespread and deep that leads one to conclude they will not be ever applied. This is precisely president Trump’s rationale: the situation will be so unbearable that Mexico will agree to his conditions no matter how extreme. The problem is that it is unbearable on both sides of the border. The pain inflected by trade frictions with China is in fact much less than the disruption of tariffs on Mexican imports would cause even if Mexico does not retaliate. Trade in North America is driven by joint production. Charging duties on inputs, parts and components as they cross the border makes the deep economic integration that exists impossible: if tariffs proceed there will be long delays at the border while custom officials figure out how to charge for them and plants will lay idle in the United States, Mexico and Canada as shifting parts back and forth becomes unprofitably.

Strategically, it is hard to fathom a more pernicious way to push Mexico away from free markets and free trade. The collapse of bilateral trade would be interpreted by many in Mexico as a confirmation that it was misguided to pursue the opening up of the economy and a deeper integration with the United States in the first place.

Trump’s proposal has put his own government and Mexico’s in a bind. The solution to this impasse does not lie in a system where the United States would certify and punish Mexico for alleged lack of cooperation. The truth is Mexico is an indispensable partner for the United States in terms of security, migration, law enforcement and trade so that it does not deserve to be treated as a national security risk. Thus, President López Obrador, don’t blink.

Beatriz Leycegui

Even if Mexico imposed 100 percent tariff rates on the total of imports from the United States on the list of products it has previously applied retaliatory tariffs, from June and until December 2019, the retaliation value would only reach 16.2 percent of the damage generated by the tariffs imposed by the United States.

Therefore, it would be necessary to identify which other products and other NAFTA commitments Mexico could suspend in order to be compensated (e.g. services, government procurement). In that exercise, Mexico must apply the same criteria it adopted in its past retaliation: not to affect Mexican production chains, as well as prices of the products of the basic food basket, and very importantly, that the measures are aimed at the companies, sectors, and actors that can exert the most pressure before the authorities of the United States.

It is time for the economic actors on both sides of the border to react strongly to a measure that is flagrantly in violation of NAFTA and the agreements signed under the World Trade Organization. Previously, Mexico’s intervention has been critical to stopping President Trump at different times from notifying Mexico and Canada of his intention to withdraw the United States from NAFTA. It has also been reported that this new measure will be challenged in the courts of the United States for not meeting the requirements provided for in the International Emergency Economic Powers Act.

In the face of serious disturbances in President Trump’s thinking and behavior, the immediate treatment on Mexico’s part must be firmness in the defense of the legal framework that has governed our relationship for the past 25 years, and that has contributed to greater competitiveness and growth of the region.

Authors

Advocate for Latin America, Refugees International

Director of Policy and Strategic Initiatives, Seattle International Foundation

Mexico Institute Advisory Board Member; Chairman, México Evalúa; Former President, Consejo Mexicano de Asuntos Internacionales (COMEXI); Chairman, Center for Research for Development (CIDAC), Mexico

Assistant Secretary for International Affairs and Chief Diplomatic Officer for the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Policy, and Vice President of INTERPOL for the Americas Region

Managing Director, De La Calle, Madrazo & Mancera and former Undersecretary, Ministry of Economy, Mexico

Mexico Institute

The Mexico Institute seeks to improve understanding, communication, and cooperation between Mexico and the United States by promoting original research, encouraging public discussion, and proposing policy options for enhancing the bilateral relationship. A binational Advisory Board, chaired by Luis Téllez and Earl Anthony Wayne, oversees the work of the Mexico Institute. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Mexico and Central America in Trump's Second Term

Dr. Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera: Crossing Borders in Research and Policy