In 1999, Georgian President Eduard Shevardnadze confided to an American diplomat that the Kremlin had asked to use military bases in his country to attack Russia's rebellious region of Chechnya, on Georgia's northern border. Shevardnadze said that after careful thought, he declined. "The is the first time in two hundred years we have told the Russians no, and they will never forget it."

Shevardnadze came to international fame as Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev's foreign minister from 1985 to 1991, and his partner in loosening the grip of Soviet rule through the glasnost (openness) and perestroika (rebuilding) campaigns.

Shevardnadze earned the enmity of hardliners in Moscow by helping Gorbachev let go of Warsaw Pact allies in Central and Eastern Europe, leading to the overthrow of all six communist regimes. He negotiated the withdrawal of Soviet forces from Afghanistan, and the peaceful reunification of Germany.

Shevardnadze's public warning of an impending coup attempt by reform opponents went unheeded. In August 1991, it came, but failed. The collapse of the USSR was foreordained, and on December 25, 1991, a humbled Gorbachev signed the dissolution of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

Shevardnadze's fame first came in his native country of Georgia. Joining the communist party at the age of twenty, he rose fast through the ranks by fighting corruption, in what was then the Soviet Sicily. Assuming the helm of the Georgian party in 1972, he pursued agricultural reforms that offered more incentives to farmers. But Shevardnadze was not above using coercion and cunning to achieve his aims, earning him the nickname of “the Silver Fox”.

In 1992, following a coup against Georgia's disastrous first president, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, Shevardnadze accepted calls to return home to restore order. His record was uneven. Armed groups waged war against separatists in Abkhazia, and Shevardnadze failed to stop them. In South Ossetia, he reached a shaky cease-fire with Russian President Boris Yeltsin, forestalling a wider conflict. Georgia lost control over both territories.

Over time, Shevardnadze neutralized a number of Georgian gangs, and by the mid-1990s, he brought the country to an uneasy peace. The hundreds of thousands of Georgians displaced from the separatist areas, however, posed humanitarian and security challenges.

Georgians had lived better than most Soviets and many were well educated. They had expectations for a better future, and Shevardnadze responded. He nurtured young leaders from the Green Party, and they created the basis for a political party he led. In relatively free elections in 1995, Shevardnadze was elected president and they won a majority in parliament. With IMF and Western aid, Shevardnadze launched reforms and introduced a new currency, the lari. Independent media and NGOs blossomed.

Soon, however, Shevardnadze, like Yeltsin a few years earlier in Moscow, began to lose confidence in and influence over his young and dynamic reformist allies. He became uncomfortable with the sharp give and take of political debate. Reforms slowed, corruption deepened, and the economy stagnated.

Shevardnadze saw himself as a market reformer, but was afraid of loosening the reins of government power. When the lari came under pressure, he wasted foreign exchange to defend its value against the dollar. Western diplomats and the IMF persuaded him that the currency would not collapse if it were floated, and it did not.

The security services, including police and military, were a frustration. Unlike in Russia where they remained unreformed, Shevardnadze sought to improve Georgia's. He moved with hesitation, however, and they became more entrenched. He lamented privately that he had lost control over them.

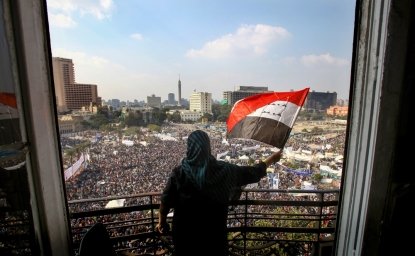

Remembering the savagery of earlier Soviet uses of force to quash public demonstrations in Tbilisi, Shevardnadze did not call out the security forces to halt the Rose revolution.

Some family members benefited from Shevardnadze's position. But he and Yeltsin were two of the few Soviet holdover leaders who did not garner vast wealth from their positions. Shevardnadze spent his final years not in a resplendent mansion, but a modest state guesthouse.

Russian security forces hated Shevardnadze for his role in the demise of the Soviet empire. They sought revenge by abetting several assassination attempts. He was lucky to escape with only some loss of hearing.

Shevardnadze’s and Georgia's struggles offer lessons for today.

First, even though Shevardnadze sought stable and productive relations with Moscow, hardliners there failed to reciprocate. Georgians were embittered and their next president, Mikheil Saakashvili, often lashed out at Kremlin leaders.

Second, Russia's assaults and occupation of Abkhazia and South Ossetia were aimed not just at Georgia. They sent a message to all of Russia's neighbors. Like the aggression against Ukraine today, Russia's strategy in Georgia reflected an urging to change borders by force and subterfuge.

Third, as in Ukraine, the strength of civil society and independent media and an increasing vocation for Europe are reasons for optimism for the future. That Shevardnadze allowed and nurtured these changes for over a decade is a lasting gift to Georgia.

Despite his personal contradictions, Shevardnadze kept Georgia independent during a critical period of its history and helped lay a foundation for its democratic future.

This article was originally published in The National Interest.