As 2014 began, few in Russia could have imagined how far its fortunes would fall by year’s end. Russia is entering strategic decline. It has options for recovery, but as yet shows little sign of exercising them.

This year Russia saw setbacks on three main fronts: economics, political and social, and foreign policy.

A severe financial crisis has hit Russia, and next year its economy may slide into a deep and persistent recession. Oil prices have plunged by about two-fifths, yet Russia depends on oil and gas exports for the majority of its state budget. Stock prices relative to earnings are the lowest of any emerging market. Western sanctions in response to aggression in eastern Ukraine have cut off most financing from the West, yet Russians must repay or roll over $150 billion in loans by the end of 2015.

These factors and the temporary detention of a well-known business leader have frightened investors. Further, corruption and state economic interference stifle private initiative, and bloated state enterprises such as Rosneft are subsidized. Without major changes, the economy will not recover in anything like the two years President Vladimir Putin predicted last week. He offered no strategy for recovery. Instead, he is avoiding liberalizing reforms and hoping that oil prices will rise and reserve funds will see Russia through.

Although the latest poll found that four-fifths of Russians still back Putin, repression is squeezing political life and civil society. Memorial, a history and human rights group, is being shut down. Aleksei Navalny, Putin’s main political foe, may go to prison for a decade on false charges. Demographic problems are significant, e.g., one-fourth of men die before the age of 55, versus 7 percent in the United K. More people emigrated from Russia in the first eight months of 2014 – just over 200,000 -- than in any recent full year.

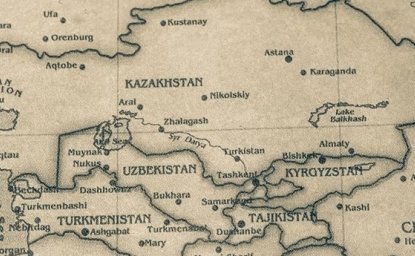

Aggression in Ukraine has alienated Russia’s neighbors and led to unprecedented isolation from the West. In October, Belarus President Aleksandr Lukashenko called it “unacceptable that some state violates territorial integrity." Last week European Union leaders boosted sanctions on Crimea and urged Putin to make a "radical change" on Ukraine, while President Barack Obama signed into law a bill authorizing tighter sanctions. Russian propaganda and military intimidation in the Baltic Sea region have angered many in Europe and failed to weaken its sanctions.

Taken together, these are telltale signs of strategic decline. Russia can mitigate them, or turn around adversity, but this requires a new course.

The West is seeking the removal of Russia’s threat in eastern Ukraine in return for an end to most sanctions, a bargain Moscow ought to accept. This means implementing the Minsk ceasefire agreement, withdrawing support for armed rebels in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine, and helping Kiev restore control and the war devastated economy there. The West would then remove the most biting sanctions, such as limits on access to Western capital markets and sensitive technologies. Russia would escape having to subsidize devastated areas in the Donbas, although it would still face this task in Crimea.Over time, Russia has more opportunity to fend off strategic decline.

It can reduce the scope of state-controlled enterprises, the least productive part of Russia’s economy. One-quarter or less of Russian GDP derives from small and medium-sized firms, well below the proportion in developed countries. Independent energy companies in Russia have shown the dynamism of private enterprise when allowed to compete. Innovative private firms often partner with foreign counterparts, which would bring more international stakeholder support for Russia’s future.

Russia can gain by leveraging the EU’s eastward reach, not repelling it. Europe will remain Russia’s most important economic partner, even as ties with China burgeon. To benefit its Eurasian Economic Union, Russia should reach out to Brussels to find ways to make it more compatible with the prosperous EU region. Better financial transparency and regulation in Russia would help it gain more access to international capital markets.

Nowhere can Moscow do more to reverse decline than by improving ties with neighbors. Ukrainians will long resent Russia’s aggression. Now that Moscow has cancelled its proposal for a South Stream gas pipeline via the Black Sea to Europe, Russia has an incentive to reach accommodation with Ukraine, its largest gas customer and transit country. This would bring greater benefit than trying to route gas intended for Europe through Turkey. Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko appears ready to negotiate. Cooperative relations with Georgia, Moldova and the Baltics are in Russia’s interest.

Russia is multi-ethnic and multi-confessional, but nationalistic policies that alienate minorities will weaken it. A more inclusive concept of patriotism would help. Mistreatment and strict language requirements may cause an exodus of migrants that will deprive the economy of labor and skills, which are especially important for small and medium-sized business.

Russia relies on nuclear forces to bolster its image as a great power, but putting them at the center of its expensive military modernization program is of dubious value. The military needs resources to counter immediate threats, such as terrorist flows from the Islamic State group (Chechens are among its leaders) and Afghanistan. They could feed insurgency in the North Caucasus and terrorism throughout Russia. The drawdown of Coalition troops from Afghanistan increases the risk of fighters migrating northward. Creating an effective counterinsurgency capacity will require new military capabilities.

All of these steps can help Russia build domestic strength and regain international stature. Few expect that Moscow will cede Crimea or end its opposition to NATO expansion anytime soon, but Russia can still begin to reverse strategic decline. Expanding opportunities for Russia’s people, reforming the economy, and improving relations with neighbors are the way forward.

The opinions expressed here are solely those of the authors.

This article was originally published in U.S. News and World Report.