Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has resurfaced the viability of the Ottawa Treaty–a multilateral treaty prohibiting the use, production, transfer and stockpiling of anti-personnel (AP) mines. For countries with hostile neighbors, landmines are considered a potent conventional deterrent. As a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 political figures in Finland and, to a lesser extent, Estonia have raised the possibility of wholesale withdrawal from the Treaty. If this rhetoric is actioned, it would mark the first time any state has withdrawn from the Ottawa Treaty and could significantly undermine its long term viability amid peer to peer conflict on the European continent. This reflects the wider concern of the limited influence of multilateral bans to the will of voluntary signatories. This article does not endorse either side of this debate, instead it seeks to explore the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on the long term viability of the Ottawa Treaty.

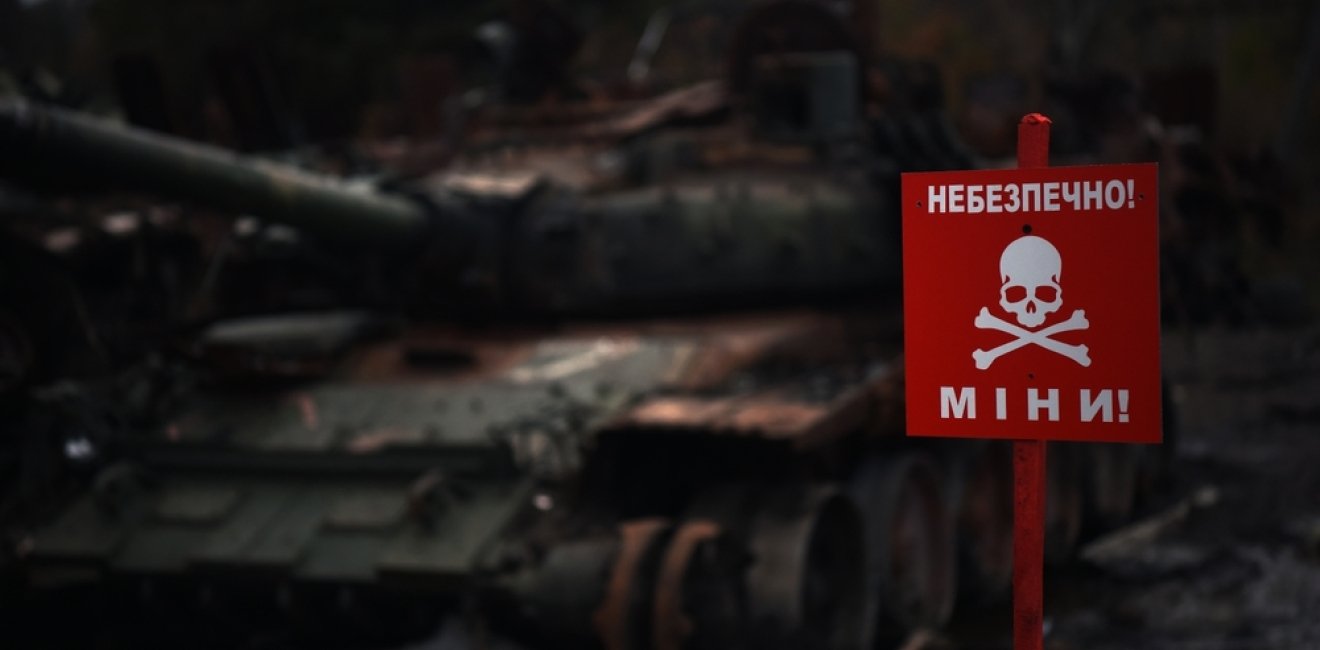

Landmines, whether anti-tank (AT) or anti-personnel (AP), are a potent conventional deterrent to potentially hostile states. The US Department of Defense (DoD) categorizes landmines as ‘area-denial systems’, which can ‘obstruct, channel, and delay/stop’ enemy forces. Such a capability could prove vital for a state sharing a land border with an aggressor, as reflected by India, Pakistan, and the Republic of Korea, among others, all forgoing the Treaty. While the US has recently changed its AP landmine policy to prohibit use, production, transfer and stockpiling, not signing the Treaty allows Washington to both support ‘Humanitarian Mine Action’ and maintain a critical conventional deterrence.

Despite their utility, AP mines have long been a controversial aspect of modern militaries’ arsenals. Multilateral efforts to curtail the production and deployment of AP landmines have received widespread acceptance and are a core tenet of United Nations (UN) disarmament efforts, such as the 1983 Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) and the Ottawa Treaty of 1997.

Catalyzed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, this dormant issue has re-emerged with today’s discussions closely mirroring those from a decade earlier–with similar rhetoric and division.

The Ottawa Treaty, signed in 1997, prohibits the use, stockpiling, production and transfer of AP mines. Although signed or acceded by 164 states, none of the major military powers have signed it, including Russia, China and the US. It should be noted that whilst the US is not a signatory, and uses landmines on the Korean peninsula, it does adhere in principle following a Biden administration announcement in 2022. As a result, every NATO member state is a signatory or agrees in principle. Critically, no aspect of NATO membership criteria would prevent a state from withdrawing from the Treaty, nor does it require states to subscribe prior to joining. As a result, there is no true institutional barrier to state withdrawing and is therefore down entirely to a country’s leadership.

Political Discussion Following Russian Aggression

With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine marking the return of large-scale war to the European continent, the discussion around the Ottawa Treaty has resurfaced among certain countries neighboring Russia, most notably in Finland. Despite initial controversy in the run-up to Finland signing the Treaty in 2012, the decade leading up to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 saw minimal opposition to Helsinki’s continued support. However, catalyzed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, this dormant issue has re-emerged with today’s discussions closely mirroring those from a decade earlier–with similar rhetoric and division.

The increased calls to leave the Treaty are clear in Finland, where many parties, politicians and citizens have come out to oppose Finland’s current adherence to it. With the 2023 Finnish election resulting in the most right-wing government in recent history, three out of the four coalition parties have voiced opposition to Finland’s membership of the Treaty. The Treaty was subject to discussion when forming the coalition in spring of 2023, although no decisions were made regarding Finland’s policy, with Finland’s recent NATO membership as the focal point for security and defense watchers. Many of the leading candidates running in the 2024 Finnish presidential elections, including Alexander Stubb, Mika Aaltola and Jussi Halla-aho have all voiced opposition in the past towards the Treaty, the topic is likely to receive a lot of attention during the election campaign underway and due to run until the end of January 2024.

There have also been increased calls to leave the Treaty in Estonia, with Estonian Parliament voting in January 2023 on a bill to withdraw from the Treaty. The bill was ultimately rejected by 30 to 21—but it showed increased support among Estonia’s right-wing parties to withdraw. Increased calls to leave the Treaty shows the issue is once again becoming a polarizing topic in Estonian politics. However, unlike in Finland, the parties advocating to leave the Treaty don’t have a strong position in the current parliament; the situation is unlikely to change in the near-term due to the next elections not taking place until 2027.

Dimensions of the Ottawa Treaty

For opponents of the Treaty, the ban of AP mines represents a curtailing of a defensive capability by restricting a cheap and effective conventional deterrence—especially considering Finland has a 800 mile long border with Russia. They argue that the AP mines are a defensive capability necessary in the wake of bordering an aggressive state, with the weapons reducing the risk of conflict and thus casualties. For its supporters, the Treaty represents an important aspect of disarmament and reducing the long term cost for local communities. This extends to the belief that leaving the multilateral agreement would tarnish Finland’s reputation among allies and the international community. Questions have also been raised about the practicalities—such as funding, production and logistics—many financial institutions have placed funding restrictions on activities around AP mines.

The design of the Ottawa Treaty adds another dimension to the discussion. Under the provisions, a country can leave the Treaty six months from submitting the instrument of withdrawal “though it will not take effect if the country is engaged in armed conflict.” Ukraine can’t thus leave the Treaty at the moment without breaking an international commitment, something that opponents in both Finland and Estonia have noted. The growing appetite to leave the Treaty can thus be linked to increased needs to establish access to a conventional deterrence before a conflict breaks out. Above all else, any potential polarization on landmines stands only to weaken international resolve. Any attempt to disengage with long-standing multilateral humanitarian law risks a significant distraction from cooperation among NATO allies, which is paramount for both Ukraine and wider European security. Adherence to the Ottawa Treaty and other multilateral weapon bans are a core pillar of international humanitarian law. Withdrawal would set a dangerous precedent for the continuation of the international rules-based order.