Many countries around the world struggle with corruption and its impacts on society, including economic problems, social inequality and violence, and public distrust in government. Corruption remains more prevalent in emerging countries due to obstacles like impunity, insufficient oversight, and widespread patronage. The issue is of chief concern to Brazilian voters following the largest corruption scheme in the country’s history, as uncovered by the ongoing Lava Jato (Car Wash) Operation, in which more than 200 people have been convicted. Although the operation has become somewhat controversial, and faces allegations of political bias, it is supported by 84 percent of the population.

Brazil has laws on the books to prevent and reduce corruption, although enforcement has traditionally been lax. For example, Brazilian Law No. 8.429/92, which became effective in 1992, defines civil sanctions applicable to public agents who use their position for personal gain. Brazil is also a signatory of three international anti-corruption conventions: the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention, the UN Convention Against Corruption, and the Inter-American Convention Against Corruption. Nonetheless, impunity is common, particularly at the higher levels of power. Several new developments have strengthened the judicial system’s capacity to investigate and prosecute corruption, including the introduction of plea bargains and the 2014 Clean Company Act, leading to noticeable progress in anti-corruption efforts. However, as the investigations expose the extent of corruption in Brazil, its citizens’ perceptions of corruption have worsened. Transparency International’s 2017 Corruption Perceptions Index saw Brazil fall from 79th in 2016 to 96th in 2017—its worst position since 2012. Public opinion polls reveal that 95 percent of Brazilians think politicians are not transparent, and honesty (i.e., not being corrupt) is the main characteristic voters are looking for in congressional candidates.

With more than 90 percent of deputies named in Lava Jato running for reelection, millions of Brazilian voters are leaning towards more populist candidates, as opposed to candidates from traditional parties. The candidates’ own legal standings and their plans to combat corruption are expected to heavily inform voters’ decisions.

Related Content

POLICY BRIEF | Governance and Organized Crime in Brazil

Click here to return to Understanding the Issues.

Authors

Department of Government, Georgetown University

Brazil Institute

The Brazil Institute—the only country-specific policy institution focused on Brazil in Washington—aims to deepen understanding of Brazil’s complex landscape and strengthen relations between Brazilian and US institutions across all sectors. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

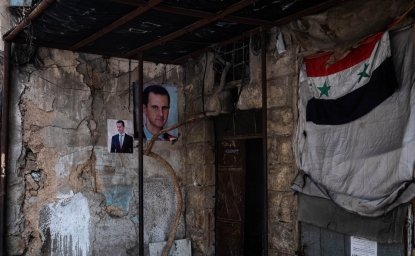

Assad's Reign Ends: Rebel Forces Overthrow Decades-Long Rule in Syria

Political Turmoil in Pakistan: No End in Sight